James Brown, ‘Out of Sight’ (“The T.A.M.I. Show”)

James Brown, ‘Prisoner of Love’ (“The T.A.M.I. Show”)

James Brown, ‘Please, Please, Please’ (“The T.A.M.I. Show”)

James Brown, ‘Night Train’ (“The T.A.M.I. Show”)

James Brown, all four songs from “The T.A.M.I. Show”

James Brown, all four songs from “The T.A.M.I. Show”

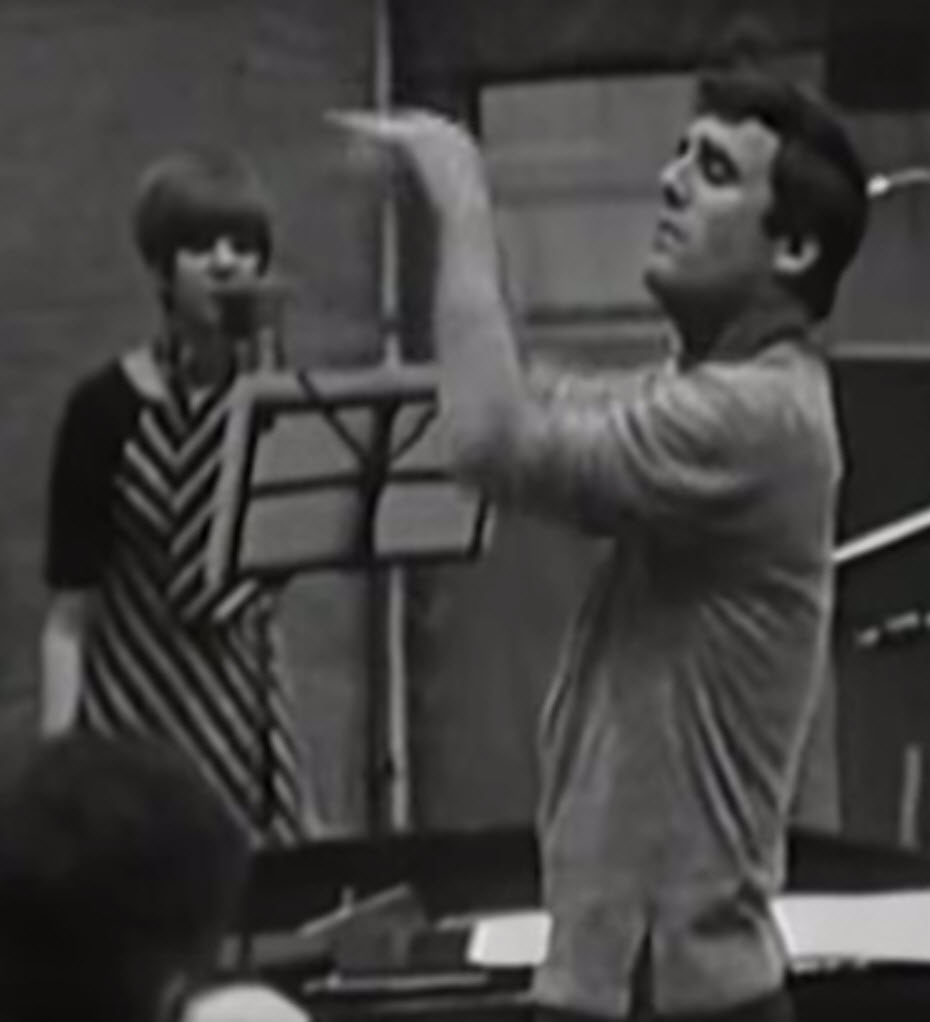

In December, 1964, a legendary music video was made called “The T.A.M.I. Show”, with a remarkable roster of stars of the day giving career-defining performances, captured on an early version of HD-TV.

In December, 1964, a legendary music video was made called “The T.A.M.I. Show”, with a remarkable roster of stars of the day giving career-defining performances, captured on an early version of HD-TV.

And it’s remembered frequently because The Rolling Stones agreed to close the show, following James Brown, which Mick Jagger still good-naturedly rues as the biggest mistake of his career.

I admit I’ve never been a big fan of James Brown, even though I’m aware that behind the pro wrestling façade of silly drama and staged emoting, he is a musician’s musician, together with his Famous Flames. As a bandleader and performer, “The Godfather of Soul” is considered the epitome of tightness in all aspects of performance, not to mention being the inventor of funk and the source of what Michael Jackson bleached and diluted with such great success.

But I do admit that the four songs he performs on The T.A.M.I. Show are probably the most intense and exciting performance I’ve ever seen.

James Brown is a better performer than I am a writer, so I’m not even going to try to describe in mere words how energy-charged these performances are. How you’re really admiring The Famous Flames’ moves (in ‘Please, Please, Please), and then you see James stomping his feet like a baby throwing a tantrum, and get that he’s stomping in perfect triple time. Or how he falls to his knees in utter faux counterfeit exhaustion and lands SLAM! on the downbeat.

James Brown is a better performer than I am a writer, so I’m not even going to try to describe in mere words how energy-charged these performances are. How you’re really admiring The Famous Flames’ moves (in ‘Please, Please, Please), and then you see James stomping his feet like a baby throwing a tantrum, and get that he’s stomping in perfect triple time. Or how he falls to his knees in utter faux counterfeit exhaustion and lands SLAM! on the downbeat.

Seeing is believing. Or in this case, maybe not. It was Edgar Allan Poe (of all people) who wrote “Believe nothing you hear, and only one half that you see.” Apparently Edgar had seen The T.A.M.I. Show.

James Brown ‘warms up’ with ‘Out of Sight’ and ‘Prisoner of Love’. ‘Warms up’ is somewhat of a misnomer, since the heat he generates there can compete with that generated by the sun on a Nevada afternoon in mid-July. But even that unlucky old sun can’t compete with ‘Please, Please, Please’ and especially the encore ‘Night Train’.

‘Please, Please, Please’ showcases his dancing and introduces the WWE cape-trick routine. It really does defy the imagination. But wait. Then comes the finale:

‘Please, Please, Please’ showcases his dancing and introduces the WWE cape-trick routine. It really does defy the imagination. But wait. Then comes the finale:

‘Night Train’, his encore, includes no less than six false endings, and everyone’s on their feet, screaming for him to come back: the 14-year old black girls, the 14-year old white girls, the band, the three backup singers, and you, and me. All of us. And we really mean it.

Maybe someday I’ll come back and walk you through the entire T.A.M.I. Show (“Teenage Awards Music International” or “Teen Age Music International” if you’re boning up on your trivia):

- Jan and Dean (hosts)

- Chuck Berry

- Gerry and the Pacemakers

- Smokey Robinson and The Miracles

- Marvin Gaye

- Lesley Gore

- The Beach Boys

- Billy J. Kramer and The Dakotas

- The Supremes

- The Barbarians (aka The Wrecking Crew, the legendary conglomeration of LA studio musicians, who played on most of the best music any of us have ever heard)

- James Brown and The Famous Flames

- The Rolling Stones

But today I’d like to take a look at the musical backdrop to The T.A.M.I. Show.

Top 40 radio circa 1964 was brutally white and commercial. For those of you born too late to remember, until the late 1960s, AM radio was largely segregated–there were (white) Top 40 stations, (black) Rhythm and Blues stations, (rednecked) Country stations, and in the big cities Classical or even Jazz. FM was exclusively the purview of Classical music until the late 1960s.

Top 40 radio circa 1964 was brutally white and commercial. For those of you born too late to remember, until the late 1960s, AM radio was largely segregated–there were (white) Top 40 stations, (black) Rhythm and Blues stations, (rednecked) Country stations, and in the big cities Classical or even Jazz. FM was exclusively the purview of Classical music until the late 1960s.

As a kid, I was a member of the Caucasion persuasion, so I listened to white pop stations. The black music I was exposed to consisted mostly of black music in white face (Johnny Mathis, Nancy Wilson) or black music diluted till it was a very light shade of ebony (The Supremes).

Heaven only knows how WSAI compiled the Top 40 charts, which were the maps of my youth. An amalgam of sales, quirky taste and payola, I’d assume. Let’s take the 1964 Top 50 as an example. The mainstays were no surprise: Beatles (5 songs), surf music (3), Motown (3), the Four Seasons (2), the early British Invasion (3) —they were indeed what my friends and I listened to.

But there was always a strong presence of impossible white boxer shorts Republican-voting ‘hits’ that no one I knew had ever willingly sat through, let along purchased: ‘Hello, Dolly’, Louis Armstrong (#3); ‘Everybody Loves somebody’, Dean Martin (#10); ‘Dominique’ The Singing Nun, (#11); ‘Java’, Al Hirt.

But there was always a strong presence of impossible white boxer shorts Republican-voting ‘hits’ that no one I knew had ever willingly sat through, let along purchased: ‘Hello, Dolly’, Louis Armstrong (#3); ‘Everybody Loves somebody’, Dean Martin (#10); ‘Dominique’ The Singing Nun, (#11); ‘Java’, Al Hirt.

On the far end of the spectrum, you also had the occasional real R&B hits sneaking in: Rufus Thomas’ ‘Walkin’ the Dog’(#41) and Garnett Mimms’ ‘Cry Baby’ (#50).

What’s the difference between those two and the other black artists on the chart? You got your Motowns, ranging from pop-light whitefaced ‘Where Did Our Love Go’, the Supremes (#15); to smooth, commercial but with James Jamerson’s so-cool ‘Canadian Sunset’ bass on ‘My Guy’, Mary Wells (#7); all the way to ‘Can I Get a Witness’, Marvin Gaye (#34), displaying some real grit.

And then you have an amazing sundry group of ‘others’:

- Lenny Welch’s ‘Since I Fell for You‘ (#19) (a 1945 R&B hit on its way to becoming an almost-standard)

- Ray Charles himself with ‘Busted’ (#40), a Johnny Cash cover! That Ray invented crossover.

- Curtis Mayfield & The Impressions’ ‘It’s All Right’ (#22), that unique precursor of singer-songwriter soul.

Dionne Warwick’s ‘Walk on By’ (#48) and The Drifters’ ‘Under the Boardwalk’ (#21), both recorded for white record companies specializing in blacks making music written and produced for them by Jews, aimed at the merging market of both young blacks and whites. That might sound like an irrelevantly obscure niche—until you take into account that pop music don’t get no better than these two songs, and there are many other indisputable classics cut from exactly the same cloth.

Dionne Warwick’s ‘Walk on By’ (#48) and The Drifters’ ‘Under the Boardwalk’ (#21), both recorded for white record companies specializing in blacks making music written and produced for them by Jews, aimed at the merging market of both young blacks and whites. That might sound like an irrelevantly obscure niche—until you take into account that pop music don’t get no better than these two songs, and there are many other indisputable classics cut from exactly the same cloth.- And that’s not including Shirley Ellis’s novelty ‘Nitty Gritty’ or Dusty Springfield’s “Wishin’ and Hopin’” (what’s the opposite of an Oreo?).

So in 1964, the heyday of the Civil Rights Movement, radio was still segregated. But look at the audience of The T.A.M.I. Show. Free tickets had been distributed to local Santa Monica high school students. Look at the shots of the audience during James Brown’s set: white teenie-boppers screaming at black acts together with black teenie-boppers screaming at white acts. That’s what social change looked like in real life. Well, ‘real life’ for those of us for whom the music was the mainstay of our reality.

The pictures here are all in black and white. But soon everything would be multicolored.

Of course, the late 60s race riots were just around the corner. But already for us in 1964, it was clear that a change was gonna come.

James, a belated tip of the hat. I just watched ‘Night Train’ for the umpteenth time – and I still only half believe it.

Don’t know where you lived in the late 50’s, but in Los Angeles, radio was definitely NOT segregated.

KFWB was the popular “Top 40” station, and they played such artist as Clyde McPatter, Dee Clark, Marv Johnson, Jerry Butler, The Drifters (LONG before Under the Boardwalk), The Coasters and many others on a regular basis.

At to James Brown, he could NEVER compare to Jackie Wilson…another artist who was “cross-over” from 1956 until he was felled with a stroke on stage in 1975. Jackie Wilson had no equal…it is unfortunate that there is no footage of his concerts in the 50’s and 60’s. James Brown learned from Jackie. Jackie was a much bigger star than James in the 50s and early 60s, and JACKIE put James on HIS shows. Even when Jackies recordings, between 1964 and 1966, didn’t chart as high as they did earlier, his concerts were sell out and he would headline while other artist on the bill, who at the time might have a much bigger record out at the time, would settle to be lower on the bill. Most requested to be on as far from Jackie as possible as they knew, you could not follow Jackie on stage.

It is a shame that Jackie Wilson’s career and achievements have been largely forgotten, even though he place over 50 hit records on the Billboard R&B/Top 100 Charts…Including 6 #1 R&B Hits and number of Top 10 Pop Hits.

Having seen both artist, there is no comparison, Jackie Wilson, was “Mr. Excitement” and there will never be anyone his equal.

There is a rawness to James Brown’s voice, his look and performance.

Jackie Wilson was polished and masterful, a much smoother and melodic voice without a hint of the gravel that accompanied a James Brown song. Jackie was beautiful to look at, always smartly dressed and together. He was classy and a consummate performer.

James was sweaty, imperfect, but the intensity jumps out at you.

There’s a reason my six year old grandson takes to the floor and tries to imitate his voice and moves.

Bravado, vulnerability,

Maggie,

Play your grandson “Reete Petite” or “Baby Workout” and see what happens.

I can’t wait to hear the results of this little social science experiment!

James Brown is the Godfather of Soul. That is without dispute. Thanks to Jeff for displaying all the reasons why.. For music fans, there is a much larger and more significant question. Jeff and I have briefly discussed this but it needs someone deeply intrigued to uncover the answer. And I can only touch on it here. How did the British Invasion spring up from nowhere out of whole cloth? Bear with me. I know we can take an artist like Gerry Marsden, for

example, and do a complete biography down to intimate details. We’re all good at that. But the complete answer to my query can get more lost than

found in all the minutiae. Three B.I. artists performed at T.A.M.I. This is early but none of them were part of the first wave. That included the Beatles, the Searchers and the Dave Clark 5.. These are six of dozens of artists that had no previous history or role=models in the British Isles. Look at the charts.

And these artists by and large have all claimed their influencers were mostly from the U.S.A. As a side note, prevailing “wisdom” said American music

was stagnant which left the door open to the B.I. Obviously, not from the opinion of these very B.I. artists! In short, for now, from Lonnie Donegan and

the Tornados and very little of pre-70s Cliff Richard, dozens of artists exploded onto the scene in miracle time. As the Beatles said “Tell Me Why”.

That was a great video interview of Mick you posted. I didn’t know he could speak French. After the James Brown bio came out, however, I remember him saying that it misrepresented the TAMI show. If I remember correctly, he said that there was an hour between performances and the audience changed with each performance so the Stones didn’t come on immediately after Jimmy had exhausted the crowd. Maybe he said it here, too; I didn’t watch the whole thing.

I must say that Brown’s dancing stood out from that of the Motown groups. The dancing (and costumes) in most black groups seemed silly before breakdancing changed all video music dancing entirely for the better. I will add that I make the obvious exception for Tina and The Ikettes and I also liked the way The Supremes moved.

Been enjoying your columns on music for a couple years. Thanks !

“But there was always a strong presence of impossible white boxer shorts Republican-voting ‘hits’ that no one I knew had ever willingly sat through, let along purchased: ‘Hello, Dolly’, Louis Armstrong (#3); ‘Everybody Loves somebody’, Dean Martin (#10); ‘Dominique’ The Singing Nun, (#11); ‘Java’, Al Hirt.”

My parents were both lifelong Democrats. They were into all those songs and artists. We had all those records at the house.

My point? One of the reasons I enjoy your stuff is because Its a time for me to get away from the B.S. for a few minutes.

That’s a very valid question, John, and I have only a very partial answer. I mentioned the odd ‘authentic’ music that sneaked onto the charts pre-BI (Rufus Thomas’ ‘Walkin’ the Dog’ and Garnett Mimms’ ‘Cry Baby’ were my examples, but there certainly were more). Perhaps easier to detect the direct influence on the Stones than on the Beatles or Searchers. Even the sanitized Motownish stuff—not too hard to draw the line from ‘Please Mr Postman’ or ‘Baby It’s You’ to the BI. I think the germ of what was to become Rock can be found pre-BI. Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’ is only a blink away. ‘Walk Right Back’ and ‘Cathy’s Clown’ likewise. I have a theory that we shouldn’t look at Rock as a later stage of Rock ‘n Roll but rather look at R&R as one of the streams that contributed to Rock. I would try to pick a song like ‘You Can’t Do That’ or ‘You’re Gonna Lose That Girl’ as the point from which Rock emanated, rather than ‘Rock Around the Clock’. Does that makes any sense? Where Dave Clark etc came from is a mystery to me as well.

Re segregation of radio stations, I stand corrected. I was from the Mid-West. I’m sure there were more open playlists on the coasts.

The Famous Flames were a Singing Group..and James Brown was their Lead Singer . They were NOT an instrumental Funk Band.

THAT was The James Brown Orchestra. In addition to Brown, the OTHER members of the Famous Flames were : BOBBY BYRD,the groups’ Founder, Bobby Bennett, Lloyd Stallworth, and occasionally, Johnny Terry. Before his “Funk” era, James Brown & The Flames were an R&B Group. James recorded many hit records with The Flames…including PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE, TRY ME, BEWILDERED, I DONT MIND, OH BABY DONT YOU WEEP, I’LL GO CRAZY, MAYBE THE LAST TIME, THINK, GOOD GOOD LOVIN, THIS OLD HEART,PRISONER OF LOVE, THREE HEARTS IN A TANGLE, and more…

JAMES was controversially inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a SOLO Artist in 1986,because DJ’s, Music Historians, and older Fans felt that THE FAMOUS FLAMES should have been inducted WITH Brown in 1986 , because at the time , BROWN DID NOT QUALIFY as a solo artist…only as a member of THE FAMOUS FLAMES. In 2012 , The FLAMES were finally INDUCTED, and the Error was corrected.

One more thing: Most people born after 1970, refer to James as “The Godfather.” But that was NOT. his original Nickname. In the Fifties and Sixties, he was known as .”MISTER DYNAMITE.”