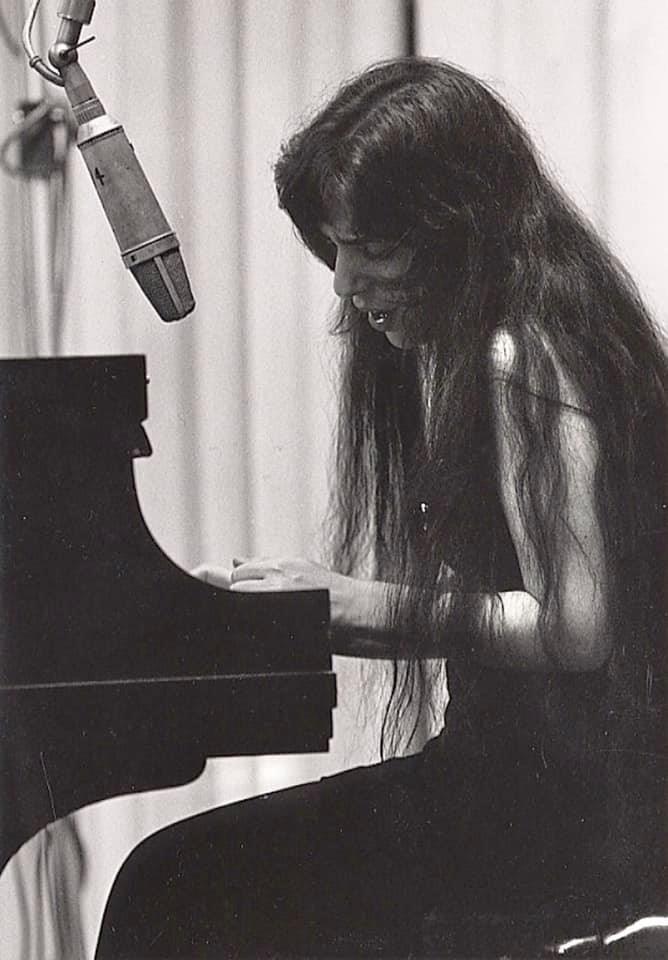

Laura Nyro, ‘Stoney End’ (Seattle bootleg, 1971)

Laura Nyro, ‘Stoney End’ (Studio recording)

Laura Nyro, ‘Flim Flam Man’ (Fillmore East bootleg, 1971)

Laura Nyro, ‘Flim Flam Man’ (Studio recording)

I have been listening to Laura Nyro regularly for a very long time – I’d guess I’ve had “Eli & the 13th Confession” binges at least three or four different times a year for the past 49 years now, probably a couple thousand times altogether. Every single time I listen, I discover new joys. And every single time, my admiration for her grows.

You do the physics. We’re talking about one big heap of admiration.

Shall I spell it out? I love Laura. She challenges me, astounds me, bewilders me, frustrates me, rivets me, inspires me, teaches me, consoles me, excites me, reassures me, loves me. She even gets me to dance.

I’ve been listening to two Laura re-issues in recent weeks. The brand-new “A Little Madness, A Little Kindness” presents a new mastering of her first two albums, “More Than a New Discovery” (aka “First Songs”) and “Eli & the 13th Confession” (released here in the original mono mix for the first time). The ear-lifted sound gives me a welcome brace of cold water. After literally thousands of listens, every new angle helps.

The obscure 2012 “Sassafras & Moonshine” is a collection of Laura covers, not always the best-known versions, 12 of the 20 cuts by black singers, hence emphasizing the omnipresent R&B (even gospel) elements in Laura’s writing and performing. It’s deepened my appreciation for a number of cuts – especially some slow ones that I always felt could benefit from a bit more focus, even commercialization, especially Mama Cass’s ‘He’s a Runner’.

So often I think of Laura as a voice from a higher world. In this recent binge I’ve been listening to this early material of hers thinking of her as a (3/4) Jewish girl a year older than myself, thereby trying to drag her down into a graspable reality by putting her into a familiar context. Even that doesn’t dispel the magic, it enhances it. I knew a lot of 18 year-old Jewish girls in 1966, and I listened to a lot of creative young musicians. Laura was – and is and I imagine always will be – unique. You can compare a lot of artists to Laura. You can’t compare her to anyone.

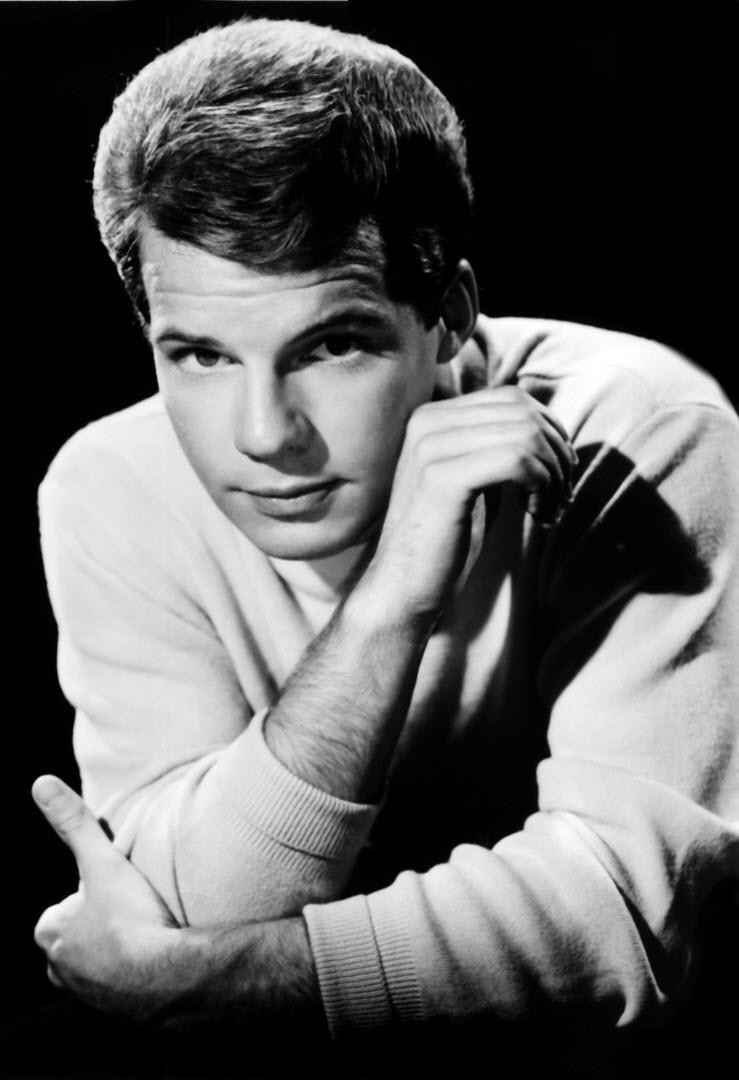

I first discovered Laura Nyro (just as I did Randy Newman and so many others) by studying and cross-checking the liner notes and the songwriting credits on record labels, internet being over twoscore years away. In this case, it was the lead cut on Peter, Paul &Mary’s (finest) album, “Album” (1966), ‘And When I Die’, written when she was 16.

I’m not going to tell you the whole backstory (you can read it elsewhere) about how in 1966 music macher Art Mogull (who had signed the very young Bob Dylan to his first publishing contract) called a piano tuner out of the phone book, who pestered him so much about his daughter’s songs that Mogull told him the 18-year old could come in the next day, how Mogull signed her on the spot (“Over a period of months, I signed [for Verve Records Al Kooper’s] Blues Project, Richie Havens, Tim Hardin, and Janis Ian”), gave her to Milt Okun to handle, how Okun gave ‘And When I Die’ to his group Peter, Paul & Mary; and then passed her on to arranger Herb Bernstein:

She was very artsy-fartsy. If you heard ‘Wedding Bell Blues’ the way she first played it for me, you wouldn’t believe it was the same song. She had that little riff—dah bah buh DOO buh DOO—that she used a lot, but she’d stop every sixteen measures and go into another tempo. I said, ‘Look, I’m as artistic as the next person, but you have to think of the commerciality of these things. If you’re gonna change tempo every thirty seconds, you’re gonna lose the average listener.’

The suits didn’t even let Laura play piano on the album. Because her sense of rhythm was idiosyncratic, Okun felt it would be hard for her to lead other musicians through Bernstein’s arrangements, so he hired a studio musician. Janis Ian: “Quite often you weren’t allowed to play on your own records. It was a lot more difficult to be treated seriously as a woman player. And you weren’t expected to be a songwriter, or to lead a band. Those were things the boys did.”

Laura’s (1947-1997) first album (released 1966, when she was 19) has always been somewhat the neglected little sister for me. Sure, it spawned more hits for her than any subsequent album (‘Wedding Bell Blues’ and ‘Blowin’ Away’ for the 5th Dimension, ‘And When I Die’ for Blood Sweat and Tears, and of course ‘Stoney End’ for Barbra Streisand.

But those covers invariably dragged the songs down into radio-friendliness, dumbed down the emotions, smoothed over the rhythmic quirkiness, sanitized the passion. Made it all sweet and non-threatening for Okun’s “average listener”. Middle of the Road-kill.

I always thought of the album as containing a bunch of great songs which were squeezed into a girdle (why haven’t those been banned along with Confederate statues?) by The Suits. I’ve often imagined the ‘What If’ album that was never recorded.

I’ve been listening a lot to live performances from the prime of her career (up to her first hiatus, 1966-72), mostly bootlegs of dubious sound quality, as well as some pretty cool covers of the first album from “Sassafras & Moonshine”, hereafter “S&M” (sic).

I wrote a whole blog posting (SoTW 233) about the amazing range of her interpretations of ‘And When I Die’, so I’m leaving that out of the discussion here. Other than ‘AWID’, I’ve found half a dozen versions of ‘He’s a Runner’, two of ‘Buy and Sell’, and one of ‘Flim Flam Man’.

I also wrote a posting (SoTW 009) about why I think Barbra Streisand was a great singer up to the age of 22, when she “traded guts for glitz and sacrificed her artistry on the altar of auto-adulation.” I’ve heard her ‘Stoney End’ all the way through maybe five times, and then only out of duty. I find it offensive – plastic, superficial, demeaning of the true original. Which I had never heard–

Until recently I discovered, tucked away inside a 1971 solo Laura bootleg from Seattle (great thanks to fellow Nyrotic Rick Sakoda), a recording of her performing ‘Stoney End’. And I got a revelatory peek at the first album that should have been. (If you care to take a trip to ‘the mythological, apocryphal real album that should have been but never was’ territory, I highly recommend Nick Hornsby’s novel “Juliet, Naked”.)

Here’s the hit version you probably know best, by Barbra Streisand.

And here’s a much more honest version by Sara Bareilles, sung at the ceremony of Laura’s induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I’ve recently become a big fan of Ms Bareilles, a most worthy benefactor of Laura’s legacy.

Here’s Laura’s studio recording (the new remastered version, girdle and all).

And here’s Laura’s 1971 Seattle bootleg version. There’s no real into or ending. She just kind of noodles into it via a bunch of minor chords (even though the song is in major), as if she doesn’t know what song she’s going to sing. At least it’s not that horrific intro Herb Bernstein forced on her.

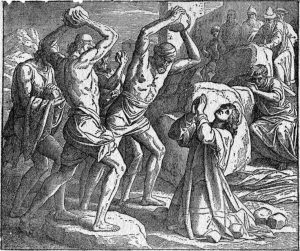

I was born from love and my poor mother worked the mines

I was raised on the Good Book, Jesus, till I read between the lines

Now I don’t believe I want to see the morning.

Going to the stoney end I never wanted to go.

Mama, let me start all over

Cradle me, Mama, cradle me again.

I can still remember him with love light in his eyes

But the light flickered out and parted as the sun began to rise

Now I don’t believe I want to see the morning…

Never mind the forecast, ‘cause the sky has lost control

‘Cause the fury and the broken thunder’s come to match my raging soul

Now I don’t believe I want to see the morning…

This ‘stoney end’ is both tempting and frightening. ‘The morning’ is bringing a new reality, a new awareness. She wants her mother’s reassurance, but she also wants to break through to this new, adult reality. She’s passionately confused. Just like a 17 year-old rock and roll sorceress. Just like a sexennial music blogger.

This bootleg reading has a minor cast to it, emphasizing the ominous aspect of the journey. But the lyric remains vexingly enigmatic. Streisand once said that she never understood the words. Laura wrote it at 17. Here I am, a grown-up male, 50 years on, still puzzling over what she meant.

I’m just so grateful I’ve discovered this version, ‘Stoney End’ the way Laura meant it, the ‘real’ version. Here are some more alternate versions of Laura songs you may or may not know, all from that neglected little sister of a first album. They may be revelatory for you, or mildly interesting, or near misses, or bloopers. That’s for you to decide.

The important thing is that you listen to Laura Nyro. Because she’s so wonderful in so many ways. Because she’s in a league of her own. Because great music deserves to be listened to. And because it will enrich you. Trust me. Trust her.

You got me listening the other day when you told me on Facebook that Wedding Bell Blues was inspired by Helen Merrill and today I just came across this interview with Todd Rundgren. Apparently, she was hard to work with and he was a fan. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=APZN_uL-z0A

And she was 17 when she wrote that.

TR was a giant fan. Produced one of her late albums.

Thank you for all the links. I can’t wait to dive into them.

OMG I needed to hear this version out loud. I’ve heard it in my head like this for ages. Better than therapy! Now where can I get the CD of this?

I’ve Loved Laura Nyro from the very beginning. I think I saw her at the Troubadour & was hooked. So many things were unique about her, the most unique being how she explained to her musicians to play more Blue, or more Green, etc. Those were MY Years, as they were Yours.. Laura, Joni, Troubadour, Ashgrove. Glad to have been raised in L.A. Thank you, Jeff, once again for your amazing works of Love.

Just wonderful , saw her in UK a couple of times, she was magnetic .

Thanks for all these discoveries of such an underrated genius.