Cantor Joseph Malovany, ‘Kol Nidre’

Uh-oh.

The big one’s coming up Sunday eve. Yom Kippur. The Day of Atonement. The Day of Judgement. The final verdict in the Book of Life.

As a boy, my Christian friends had ‘He’ll know if you’ve been bad or good.’ What was at stake was a new Lionel caboose.

I got God Himself with His indelible quill inscribing “who will live and who will die; who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by beast, who by famine and who by thirst, who by upheaval and who by plague, who by strangling and who by stoning.”

After that, you don’t need “House on Haunted Hill” for nightmares.

It all starts at the beginning of the month of Elul, 40 days before Yom Kippur, when the serious ones among us start getting up every morning (still night for me) at 4AM or some such unGodly hour to recite prayers of penitence. Then 10 days before, you get Rosh HaShana – two full days of wearing white, dipping apples in honey and spraying your dress shirt with pomegranate juice, hoping (praying) that He inscribes you (at this point in magic ink which takes 10 full days to dry) in The Book of Life. Or else…

Then the night before you take either a chicken or 18 units of your local currency and wave it over your head three times to transfer to it your transgressions. I’ll let you guess which means I employ.

Then the night before you take either a chicken or 18 units of your local currency and wave it over your head three times to transfer to it your transgressions. I’ll let you guess which means I employ.

On the afternoon of The Evening, here in Israel everything shuts down. By the time the sun is heading for the horizon, there’s nary a soul on the street. The radio and TV stations close down. You ask forgiveness from those you’re closest to for anything you have done to hurt them over the year, because Yom Kippur only works to absolve you of your transgressions against Him if you’ve already made amends with humanfolk. Three out of every four Jewish citizens prepare to fast.

A simple last meal, all spruced up in your finest whitery (except for the rubber-souled shoes), you take the Dead Man Walking trudge to the synagogue (or this year, the outdoor gathering of a dozen neighbors)–hoping for the best, fearing the worst, something even more ominous than the 25-hour fast that’s just begun. Water, fire, sword, beast…

You sit in your reserved seat (that cost you a pretty penny) as the cantor takes his place on the altar, and he begins that familiar, haunting chant: Kol nidrei, v’esarei, ushvuei, v’haramei, v’kinusei, v’chinuei…

כָּל נִדְרֵי, וֶאֱסָרֵי, וּשְבוּעֵי, וַחֲרָמֵי, וְקוֹנָמֵי, וְקִנוּסֵי, וְכִנוּיֵי …

The whole congregation is so geared up, so tense, so penitent, so scared out of their wits, that the guy could be singing ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ (in a minor scale) and you’d be on the verge of meltdown.

Actually, it’s not far from that. Kol Nidre is legalese, a contract. More precisely, the dissolution thereof. It’s a string of technical terms: All the vows, and prohibitions, and oaths, and pledges, and consecrations that we’ve taken upon ourselves – seven technical terms of legal commitments, English can’t keep up with them – we disavow them. We declare them null and void with another list of gibberish verbs to satisfy the lawyers.

Not only that. The prayer—I mean, the contract– is mostly in Aramaic, the long-dead lingua franca of the neighborhood, Jesus of Nazareth’s native language, the language of the Talmud. Only one sentence in the middle is in Hebrew.

Not only that. The content has no clear connection to atonement. It’s pretty much perceived as “If I said to myself ‘I swear I’m never taking this route to work again in my life’”, I’m retracting that. All my vows not involving a commitment to another person, I’m unilaterally dissolving. It’s a technicality, making sure that none of my stupid promises stick, so that I won’t get in trouble with The Big Boy for not keeping them. It’s so deeply ingrained that all year long some folks of my ilk say, “Okay, so I’ll see you for lunch on Tuesday, b’li neder” (but it doesn’t count as a vow). My next door neighbor made a point of returning to me the equivalent of a dime before The Day, lest he have any outstanding debts.

And, of course, the melody.

Some believe that the tune for Kol Nidre was given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai. The opening of Kol Nidre is what the masters of the Catholic plain-song term a “pneuma”, or soul breath. It begins with a long, sighing tone, falling to a lower note and rising again, as if only sighs and sobs could begin the prayer service.

What I’m driving at here is that it’s not the inherent content of this legalese text that moves us so on the cusp of the most solemn day of the year. It’s the moment, the state of mind and soul, the drama.

What’s the point of Kol Nidre then? For me, it’s the beginning of a 25-hour attempt to purify myself spiritually, to cleanse myself of unkept promises and transgressions by genuinely and profoundly atoning before my conscience and God. The point transcends legalese.

It’s music, the music of the Jewish soul. We all know that “music hath charms to soothe the savage breast,/to soften rocks or bend a knotted oak”, but not legal contracts.

There are countless recordings of Kol Nidre, ranging from the sublime to the profane, from the sacred to the ridiculous.

Perhaps most famous is Al Jolson’s rendition in “The Jazz Singer”, the first talkie (1927). Jack Robin (ne Jakie Rabinowitz) rejects his parents’ expectation that he will succeed his father as cantor, in order to pursue his career as a ‘jazz’ (popular) singer. In the movie, the errant, assimilated son is reconciled with his parents and his tradition. But that was a Hollywood ending, expressing the wish fulfillment of producer Sam Warner, the brother who kept peace between his two Alpha siblings Harry and Jack (unburdened by such compunctions over jettisoning their tradition). Sam died at the age of 39, marking the end of harmony within the Warner family, the day before the premiere of the movie. He was buried on the eve of Yom Kippur. Just like the movie.

I won’t even mention the 1952 remake of the film starring (Lebanese Maronite Catholic) Danny Thomas or the 1980 embarrassment starring Laurence Olivier and Neil Diamond (who like Jolson at least was an MoT).

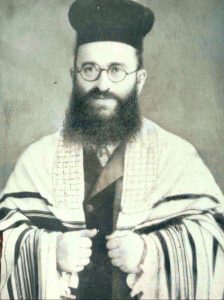

I wish my intuitive association for Kol Nidre were one of the great cantorial voices of the Twentieth Century. Yossele Rosenblatt (1882-1933) was a poverty-stricken cantorial legend in the US. The Warners offered him $100,000 (equivalent to $1.3 million today) to portray the father in ‘The Jazz Singer,’ but they could not persuade him to sing Kol Nidrei. He felt that it was too sacred to be used as entertainment. They did persuade him to do a cameo in the movie, playing himself.

Jan Peerce and Richard Tucker (brothers-in-law and fierce competitors) both began their singing careers as cantors before succumbing to the bright lights of opera.

All of these versions include instrumental accompaniment. In a traditional service, it is sung either by the cantor alone or accompanied by a male choir. Of course, it can’t be recorded or filmed due to the prohibitions that apply to the day. So these recordings don’t really communicate the starkness of the moment. Here’s one dignified, authentic version, by Cantor Joseph Malovany (b. 1941), that communicates the beauty of the music. It’s worth watching till the end, where he talks a bit about Kol Nidre.

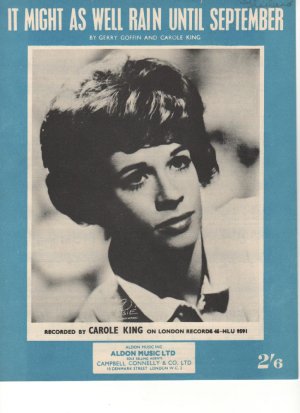

But we don’t choose our mind’s associations, and when I press the Kol Nidre button on the juke box of my mind, what comes on is the version by Perry Como (1912-2001).

Perry was the son of Italian immigrants, a barber, and one of the most popular singers of the mid-century. He was famous for his gentle voice, his calm demeanor and relaxed disposition, his cardigan sweaters, and his all-round niceness.

An example of Como’s popularity came in 1956, in a poll of young women asked which man in public life most fit the concept of their ideal husband: it was Perry Como. A 1958 nationwide poll of U.S. teenagers found Perry Como to be the most popular male singer, beating Elvis Presley, who was the winner of the previous year’s poll.

Perry had a weekly television show from 1949 till 1963, and a monthly one till 1967. That sentence bears some thought. Think of the stature of such a public figure.

In the late 1950s, Jews in the US were still living in the shadow of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust, self-conscious of the measured hospitality extended to them by their adopted country, striving desperately to achieve acceptance and security, but still excluded from many hotels and country clubs and universities and industries. My grandparents were “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore”. Many Jews of my parents’ generation sought refuge in assimilation, but most still held a complex, tenuous commitment to their faith. But we absolutely carried the awareness of still wanting and needing to be accepted.

And every year, just before the High Holidays, Perry Como – Mr Consensus – would sing Kol Nidre on network television. It was the ultimate expression of America embracing its Jews, the most reassuring promise that we were welcome and safe – perhaps the first time in history where a Jewish population would find such acceptance, such a haven.

And every year, just before the High Holidays, Perry Como – Mr Consensus – would sing Kol Nidre on network television. It was the ultimate expression of America embracing its Jews, the most reassuring promise that we were welcome and safe – perhaps the first time in history where a Jewish population would find such acceptance, such a haven.

Of course, I see things differently today. I see assimilation as an existential threat to American Judaism. I don’t know if Al Jolson’s great-grandchildren will be in synagogue for Kol Nidre this year. I will.

And I no longer depend on Perry Como for affirmation of my faith or peoplehood or personal well-being. As far as my earthly life goes, I’ve put my eggs in a much different basket. And as far as my spiritual life – well, I’ll be doing some hard and serious thinking when listening to the music of the cantor singing Kol Nidre.

“Some believe that the tune for Kol Nidre was given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai.” Do they really believe it or is it a fun folk tale.

Same with God decides if you live or die in the year to come. Do some people actually believe that or is Yom Kippur etc just a legitimate spiritual practice of self-assessment and correction?

For me it’s always been Johnny Mathis. My dad had the record at home and we played it often. The words are unintelligible but as you say the music is the point. I base my own version on his. https://youtu.be/8U7WRmle5tg

There are people who believe that Elvis is alive.

So, yeah, there are people who believe anything and everything.

I personally am pretty weak in the belief department.

I’m partial to Marc Wachpress’ version, but I actually liked Perry’s as well.

I’ll be listening to that Jazz Singer Jolson do it on Friday night.

Goose bumps.