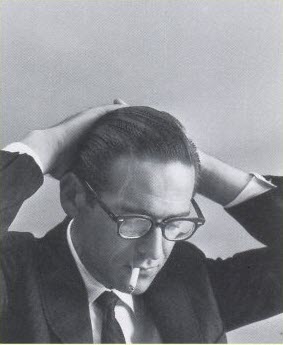

“Some people just want to be hit over the head, and then if they’re hit hard enough maybe they feel something. But some people want to get inside of something and discover maybe more richness.” – Bill Evans

I’ve been looking forward to writing about Bill Evans’ ‘Nardis’ for years. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call it the raison d’etre for this blog. It’s a song he played from its very first recording in 1959 through virtually his very last breath in September, 1980. You might well not know this music, so I’m both proud and humbled to be the vessel of this musical offering, because it’s among the most sublime and moving artistic creations I’ve encountered.

This posting is longer and more detailed than usual. It describes the arc of Bill Evans’ career and the remarkable creative outpouring during the final year of his life, focusing on a piece which accompanied him during those twenty years and then exploded into his signature confrontation with his impending death. If you have limited time or patience or interest, I urge you to skip down to the last section, The Nardis Legacy, where I describe ‘Nardis’ as played during the final months of his life by ‘The Last Trio’.

Career Overview

The career of Bill Evans (1929-1980) had an unusual curve. He hit NYC in 1956 and immediately became a sought-after sideman, most memorably in his key contribution to Miles Davis’ 1959 “Kind of Blue” (SoTW 079). Not long after this, he became addicted to heroin. In 1959, he formed his “first trio,” which reinvented the piano trio and played a key role in determining the sound of modern jazz. They recorded two studio albums. Their “Live at the Village Vanguard” session (SoTW 060), recorded ten days before the death of bassist Scott LaFaro, constitutes some of the most beautiful music I know.

Evans withdrew from the world. His manager forced him into the studio for the little-known, harrowing 1962 “Solo Sessions” (SoTW 096). He came out of the self-imposed exile due to the need to support his habit. After about half a year, he recruited young bassist Chuck Israels for the “second trio,” which operated for three years. Their output was uniformly excellent, but a cut below that of the first trio.

Evans withdrew from the world. His manager forced him into the studio for the little-known, harrowing 1962 “Solo Sessions” (SoTW 096). He came out of the self-imposed exile due to the need to support his habit. After about half a year, he recruited young bassist Chuck Israels for the “second trio,” which operated for three years. Their output was uniformly excellent, but a cut below that of the first trio.

From 1966 till 1978 Evans partnered with bassist Eddie Gomez and a series of drummers. The musical output was that of a genius coasting, feeding his drug habit, struggling to stay afloat, gradually destroying his body. The music is always graceful, intelligent, refined, but rarely as memorable as the second trio, never as breathtaking as the first.

In mid-1978, Evans (now subsisting on cocaine) found two young partners, bassist Marc Johnson and drummer Joe LaBarbera, and founded his last trio. Over the next year and a half he developed a more intense, expansive style, culminating in a creative explosion in the several months leading up to his death on September 15, 1980. According to all accounts, he sensed that his death was imminent. He played in those last months with a frenzy born of the very profoundest awareness of his own tenuous mortality. The vehicle for that expression became the set-closer, ‘Nardis’, especially the incredible solo piano introduction which Bill Evans created anew, night after night.

Early Nardis

From early 1958, alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley was a member of Miles Davis’ group together with John Coltrane. When Cannonball went into the studio to record his album “Portrait of Cannonball”, producer Orin Keepnews brought a young white boy named Bill Evans to play piano on the session. Cannonball’s boss, Miles, wrote a song for the session called ‘Nardis’.

It was a strange piece, modal (rather than chord-based), a concept Miles was just beginning to dabble in. This means that the music remains within a scale, rather than being based on shifting chords. Think ‘Fever’. Think ‘You Can’t Judge a Book by Its Cover’. Think ‘Kind of Blue’ (SoTW 079).

No one has succeeded in guessing what the name ‘Nardis’ meant. Bill Evans was a fan of anagrams. His song ‘Re: Person I Knew’ was derived from ‘Orrin Keepnews’. ‘NYC’s No Lark’ comes from the name of fellow pianist and junkie Sonny Clark. Dinars? Drains? Nadirs? Ranids? What’s a ranid?

No one even understood it musically. (“Eastern-sounding” was the best anyone could do.) Cannonball’s version is pretty embarrassing – awkward, stiff, thoroughly a flop. Evans: “You could see that the other guys were struggling with it. After the date, Miles said I was the only one to play it the way he wanted.”

By the way, Davis’ authorship has often been disputed, probably due to the fact that he never played the song and that it was so strongly absorbed by Evans. But Evans himself stated on numerous occasions that it was Miles who wrote ‘Nardis’.

Half a year later, Miles brought Bill into his group in order to further explore modal jazz, at which Evans was considered an expert. This direction would reach fruition in April, 1959, in the masterpiece “Kind of Blue” (with Adderley on alto sax) (SoTW 079).

In December 1959, Evans’ first trio recorded their first album (“Portrait in Jazz”) in which they discovered that they could levitate. In February 1961 they recorded their second studio album, “Explorations”, in which they refined the magical, gravity-defying interplay, discovering that they could dance together while suspended in the air. Alongside half a dozen tired standards which they revitalized and a couple of originals was ‘Nardis’. Listen to Adderley’s group’s arthritic stiffness. Listen to Bill Evans’ transcendent, weightless reading of what can hardly be called the same composition. It already here includes an extended bass solo, a feature that would reappear in the song over the next decades—but never again in the hands of Scott LaFaro.

In June, 1961, at the Village Vanguard, the trio would create a floating pas de trois. (SoTW 060). Ten days later LaFaro died in a car wreck.

His death sent Bill into a deep depression. Bill’s brother remembers him wandering around NYC wearing some of LaFaro’s coat. It was a bleak time. In April 1962, short of cash and in debt to his record company, Evans went unwillingly into the studio to noodle for an hour by himself in a darkened room. I discussed the resulting recordings in SoTW 096. Among the pieces Evans played is ‘Nardis’, in an interpretation as profoundly different from that by the first trio half a year earlier as is white from black, life from death. A shimmering waft becomes an open wound, transformed by naked pain. These five minutes of profound, unguarded introspection come from the place Evans would revisit 17 years later. Here he is experiencing the first tragedy of his life. There he would be facing the final one.

If the music of the second trio never reached those heights (or depths), it was infallibly impeccable. Here they are playing ‘Nardis’ in a live performance from 1964.

The Middle Years

Then came the long, relatively uneventful Gomez era, by far Evans’ longest collaboration (1966-78), the least exceptional years of Evans’ exceptional career, years where he was rarely doing anything but coasting. One can’t blame Gomez. He’s not an inferior bassist, certainly no less competent than Marc Johnson. Perhaps one should credit him with propping Evans up for all those years (a compliment that has been given to his long-time manager Helen Keane; but then Evans needed a lot of propping). Simultaneously with Gomez’ departure, Evans’ career soared. He found two young collaborators whom he credited with inspiring him to an entirely new approach. But the fact remains that all those Gomez years were Evans’ least interesting ones. Here’s a recording from the “Portraiture” album (1969) with a long, meaningless bass solo. This rendition includes a piano introduction. I’d fly to Mongolia to see Evans play like this today, but let’s face it: compared to what came before, and to what came after, he’s on auto-pilot. There are a dozen more recordings like this scattered through the Gomez years, but from what I’ve been able to find, Evans never recorded ‘Nardis’ from 1972-1979.

Here is a remarkable clip from Finnish TV, 1970, Evans and Gomez (and drummer Marty Morrell) performing it in a private home in Helsinki. Note Evans’ deteriorated state of dental affairs (a dentist fan would soon give him a new set of teeth). Note the tie and shirt. One can only assume the shirt (and its wearer) hadn’t been washed in several weeks. Note his articulateness, the precise formation of his perceptive thoughts. Note the spot-on musicianship. And this is a shadow of what he was capable of.

The Last Trio

During the short-lived tenure of the last trio, from the summer of 1979 till September 1980, ‘Nardis’ became the vessel through which he expressed a last remarkable outpouring of creative energy, growing in intensity month after month, week after week, night after night.

The song begins with a piano solo about five minutes long, followed by an extended bass solo, followed by an extended drum solo, followed by the group. Here’s an example of a complete version of the song, which usually last between 15 and 20 minutes. It was always the closer of the evening’s program. To be honest, I find the bass solos invariably bland and the drum solos annoying.

But the solo piano introductions achieve an artistic expression of a rare – if not unique – intensity.

Here’s an early version from July 19, 1978, with newly-discovered bassist Marc Johnson and drummer Philly ‘Joe’ Jones, Evans’ long-time drug buddy and musical partner from back in the 1950s. Evans often said that Philly was his favorite drummer, ever. Note how paltry Philly’s drum kit is here. Rumor is the rest was in a hock shop, pawned to feed his habit. Note also how much better his drumming is than anyone else Evans played with. This is the earliest version I know of the final format of ‘Nardis’. The gravitas is yet to arrive.

In January 1979, Joe Labarbera joined the group permanently. Here they are in Iowa in one of their first performances, at the Maintenance Shop. As Bill says in the introduction, “It’s still evolving.”

Here’s the trio in Buenos Aires in September, 1979. They’re finding the groove. It’s serious, but not yet harrowing.

Here they are on November 26 in Paris, darker by far.

Here is December, 1979, at the Balboa club in Madrid, in an energetic, forceful version.

Listening to this series of performances I think of the nature shows where a vegetable-growth slow process is compressed to a few seconds. This is a compressed view of the growth of the soul. From version to version, we bear witness to Evans’ interpretation of ‘Nardis’ deepening exponentially.

In June, 1980, a hundred days before his death, Evans returned to his favorite club for a week’s stand at the Village Vanguard in New York, the site of the great recording with the first trio twenty years earlier. Four evenings were recorded, June 4, 5, 6 and 8. They’re documented in a 6-CD boxed set called “Turn Out the Stars”. The performances of ‘Nardis’ closed each evening. They are extemporaneously improvised, each one a unique expedition into the nether limits of the human soul. The technical virtuosity Evans employs is jaw-dropping. Together, they constitute a sublime, harrowing vision.

In early August the trio appeared at the Molde Jazz Festival in Norway. Here’s a video of ‘Nardis’ from that performance.

From August 31 to September 8, 1980, the trio appeared at the Keystone Korner in San Francisco. This stay is documented in the 8-CD boxed set “The Last Waltz”. Here are the six performances of ‘Nardis’ included there:

The “Last Waltz” performances are perhaps less finely polished than those in “Turn Out the Stars”, but no less intense. Evans’ strength was failing. He died a week later, on September 15.

The ‘Nardis’ Legacy

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Bill Evans was many things – wise, and good, and wild, and grave; but he never came near old age, doomed to an early death from twenty years of self-destruction, first by heroin, in these last years by cocaine.

These piano solos are a unique expression of a man staring unflinchingly into the abyss. But what does he see? And what does he say? I’ve been puzzling over this for weeks now, and feel no closer to The Answer. I’ll tell you what they’re not—they’re not morbid or self-pitying. They’re not ‘raging’, but they certainly are crying out against the dying of the light. How will I deport myself when I face my death? Will I look for some broad, expansive, comprehensive overview of the meaning of my life, of human existence? Or, like Bill Evans in these performances. will I drive myself in a fury to dig, and dig, and dig, to get to the bottom of all this? I don’t know. I hope I’ll be old and doddering, and that I never see the truck coming up behind me, that the light goes out unexpectedly and suddenly.

Because I certainly would not have the courage, the drive, the gravity that this great artist displays as the Angel of Death embraces him closer and closer to her bosom, night after night.

What does it ‘mean’, this music? What does it ‘mean’, this life? I don’t know. I don’t know what the Grand Canyon ‘means’. But I know the utmost depth of the naked, mortal soul when I see it. Here it is. Bill Evans’ ‘Nardis’.

‘Nardis’ complete, June 8, 1980, from “Turn Out the Stars”:

Having not yet dug into the depths of BE’s music, I loved your dissection. It is well researched. It crawls out of the pit of the soul, grabs you, opens you and exposes your entrails to the world. Visceral, if there’s a better word.

As for Nardis, I love those songs that can be recognized by as little as the first two notes: What’s New and Nardis being the most prominent. Summertime on three notes.

Thank you and have a great week !

Hey Jeff

Been meaning to comment for ages…

Nardis is one of my favourite Bill Evans tracks and a good pick for a bellweather of Evans performances. The first one on the Last Waltz is perhaps my absolute pick but I never tire of hearing the tune by Bill.

As an aside thats a great quote by Dylan Thomas (though Bob took his name from him and he was Welsh rather than Irish). Britains best piano player Stan Tracy did a suite of Under Milk Wood which is quite brilliant and well looking out for.

This article is a tour de force and deserves a book all of its own.

Its a fascinating look into ‘The Mind of Bill Evans’

Well done. I shall spend the whole weekend studying and enjoying

Music to my ears! “That’s why I’m here.” Let me know what you discover.

Hey, Colin. Great to hear from you. Glad you’re enjoying the posts. Keep in touch.

Thank you for your insight Jeff !

Here is an excerpt from my book “The Big Love: Life & Death with Bill Evans” which captures that 1980 performance at the Vanguard.

“Nardis”

Alone at the Vanguard, last set of the night. Bill’s trio on the bandstand and me squeezed into the bench against the wall of the room. Bill closes the set tonight with an extended version of “Nardis”, his seven minute solo intro a distorted exploration of the Miles Davis tune he has been revisiting for 20 years now.

No one recognizes the melody; the discord has his head rearing up, an angry mane of thick grey hair framing his broad forehead, eyebrows raised in astonished agony.

Here is Bill, crucifying himself. Finally exploring his suffering in public, no longer able to contain his passion, freely expressing the distortion he is directly experiencing.

He translates this distortion for us, his listeners, so that we too can recognize the dichotomy of what is and what is not.

My heart is witnessing his public display of our private agony. How is it that our perfect love, pure being, pure light is tangled up in human ideas of perfection?

Bill describes this distortion with such fury and a great sadness. He knows the score; he knows he is checking out. He is integrating all that he has witnessed, concocting some kind of rocket fuel for his zenith.

He does not know his departure date, but his readiness is made evident to those who know how to listen.

I am waiting patiently at the back of the Vanguard tonight wondering if today is a good day to die. For surely once Bill goes, my work will be done too.

This is how I see the ending. I see myself checking out with him. I see myself staying inside the satori of our pure love, and I cannot even imagine a life beyond this vision.

Bill closes the tune with heavy chords and a question mark.

copyright 2010 Laurie Verchomin

http://www.laurieverchomin.com

The tune “Nardis” on the album “Explorations” (1961) became famous by Bill Evans, who played it for the first time in a trio setting. There is a mystery behind the identity of it’s original composer. It’s been said by Bill Evans that Miles Davis originally wrote the piece, but it has also been said by Miles himself that Evans wrote the piece. Davis wrote the song for Cannonball Adderley and the song was originally on “Portrait of Cannonball” (Riverside 1958) with Blue Mitchell (tp), Cannonball Adderley (as), Bill Evans (p), Sam Jones (b), Philly Joe Jones (d). It seems Miles composed it, but never recorded it and Bill Evans helped out with the harmony. Bill Evans did indeed announced it in one of his concerts as “a Miles Davis piece” – he did so on the “Jazz at the Maintenance Shop” DVD from Iowa, 1979. He recorded “Nardis” on innumerable albums and reworked the piece with modal explorations each time it served as the final tune of his performances. Just a week before Evans’ death on September 15, he recorded “Nardis” between August 31 and September 8, 1980 at San Francisco’s Keystone Korner on an eight-CD set. His closing signature “Nardis” is heard here in six different versions in one week, each of them with a different exploration, from a brief seven-minute version to a last performance that stretches as his swan song of nearly 20 minutes with extended unaccompanied introductions on the piano. He summarizes his entire musical experience, from jazz to Bach’s contrapuntal strictness to Bartok’s sense of dissonance. Evans introduces the tune: “We’ve learned from the potential of the tune, and every once in a while a new gateway opens and it’s like therapy.” Here he gives birth to a new music that goes beyond anygenre distinction.

Thank you, Laurie. I hope you feel I did justice to this moving body of music.

A quote from Laurie’s Website, from an interview by Sebastian Pranz for the German Magazine FROH:

The last month of his life Bill was very active and played some of his best performances. You were part of the audience – what was the atmosphere like?

There was no way you could not get what he was trying to say with his music. It was a great snapshot of his soul. Everyone was sucked into this vortex, experiencing their own version of his agony. The soul is a scary place to go to on your own. You could go there with your therapist or you could go there with Bill Evans.

This is an excellent piece – many thanks for writing such a comprehensive essay on this wonderful tune. It is especially interesting to hear the original version, which I had never heard until now.

For me, the best Nardis is the one from Molde, Norway, 9th August 1980. I love all the other versions he recorded but the Molde version is perfect. It betrays all his classical influences, goes from ppp to fff in dynamic range, is beautifully phrased and it overflows with emotion. Marc Johnson’s bass solo is one of the best I’ve ever heard him play (with a few Pastorius-style bits thrown in, which Bill clearly enjoyed – he is smiling from ear to ear at this point!) and Joe LaBarbera’s drum solo is thunderous. Bill’s opening solo is probably the best four minutes of music he ever did (and it’s a tough job to pick out the best bits of the catalogue of a jazz genius).

I loved this post so much I ran out and bought the disc. I have played the ‘h’ out of it….

I have both “Turn Out the Stars”, and “Last Waltz”; I transferred both sets to one playlist on my iPod. I’ve made several non-stop road trips – between Dana Point, CA and Portland, OR – listening to nothing else. It’s that kind of music.

For my playlist, I chopped off just the piano solos. That’s a real trip, I want to tell you.

Thanks for a very perceptive & informative piece.

I’m glad to hear someone else say that some Gomez solos

can just drone on…sometimes I wonder if he was listening to what

Bill was playing as well.

I wish some people would re-examine the Second Trio and

give Chuck Israels his due!

Again, thank you for a great piece of work!!

I feel uncomfortable bashing a paramour of Eliane Elias, but over the years I’ve found myself listening to fewer and fewer works of Bill Evans more and more. The Gomez years? Precious few albums I actually do listen to, certainly not more than once in a blue moon. Even the third trio–I just listened for a few days to the piano intros to ‘Nardis’, nothing else. I certainly don’t need those drum and bass solos, and my fingers don’t really go to put on the other stuff. Live at the Village Vanguard, on the other hand, I listen to seriously every couple of weeks.

Glad to hear there are kindred spirits out there.

Very articulate, beautiful writing. I’d love to read a novel with a voice like that. Bill Evans was a genius and you illuminated in me several realizations of different sorts. Thank you for the article.

“Nardis” is the last name of jazz critic/writer Ben Sidran spelled backwards. At least that’s what would make the most sense.

If you have ever watched the video of the trio playing at someone’s house in Finland, Bill says he was there when Miles wrote it. LOL

You will NEVER convince me that someone plays a tune like this all of his life and it’s not his.

I’m not anywhere near as talented, but I play my tunes to death.

(I don’t read anywhere near as well as a real musician, but I just can’t believe you can be that much into someone else’s work to play it that long, that many times night after night.

NEVER will I believe Miles Davis wrote “Nardis”, he was infamous for stealing tunes. INFAMOUS.

Thanks, Jeff. I’m hard at work on a novel right now. Working title: Decapede.

Stay tunes.

It’s probably my own speculation, but I can’t help connecting the Spanish flavour of this piece with the word “nardo”, which in Spanish is a common name for several scented plants.

Jeff! Thanks for letting me discover this piece. I may have heard other bits of Evans’ music, although I am not even sure, but this … is remarkable! I will study your whole essay later this weekend, but just listening to the first recording on top made my day. Thank you, friend!

While I stand in awe of the later Nardis live performances, I admire the “early” Nardis renditions. Lilting, almost casual in sound, they speak to a turbulence broiling underneath. The minor mode, the unresolved chords. Foreshadowing of things to come. I find myself reading this over and over to get every drop.

In an interview, Bill Sidran asked Miles how he came up with the name Nardis. He didn’t know. When Sidran told him it was his name spelt backwards, Miles wouldn’t acknowledge that’s where he supposedly got the name… probably because Bill very likely wrote and named the song. Wish I’d asked Bill when I met him in 1979.

Well I personally dig the Gomez Era, the live albums were my intro to Bill Evans music. I had gotten it with 8 other compact disks for 1 penny in 1986 from Columbia House. I learn something musical from every listen to every recording of Evans. Evans makes musical sense. Much is made of drug usage in the above article, but there are a lot of junkies and no other Bill Evans, funny no one ever wonders if someone’s hands hurt. But in every case made musical sense.

I think Nardis is as much a Miles composition as Blue in Green – Bill didn’t want to ruffle any feathers, so he just let Miles take the credit for Blue in Green and most likely Nardis.