Hi Everyone out in SongofTheWeekland. As I’m sure all of you remember, way back in SoTW 035, we made a promise to stroll through Miles Davis’ remarkable voyage through the 1950s.

Hi Everyone out in SongofTheWeekland. As I’m sure all of you remember, way back in SoTW 035, we made a promise to stroll through Miles Davis’ remarkable voyage through the 1950s.

In 035 we talked about the reactionary revolution of his “Tuba Band” of 1947, better known as “Birth of the Cool”. Then in 041 we visited his remarkable series of albums with his first quintet, focusing on melodic, sweet, laid-back treatments of standards. And in 055, we took a look at “Sketches in Spain”, one of three stunning large-canvas collaborations with Gil Evans (who was also an inspiring force behind “Birth of the Cool”). In SoTW 244, ‘Green Dolphin Street‘, we discussed Miles’ very first recording with a young Caucasian dude named Bill Evans, his brand-new pianist, precursing “KoB” by 10 months. (And just a bit of subtle foreshadowing, way back in SoTW 003 we wrote about Jerry Garcia & Dave Grisman’s version of ‘So What’.)

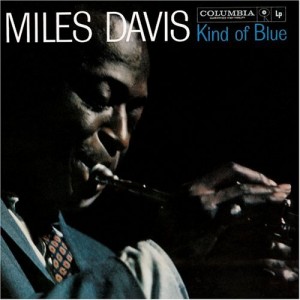

We’ve been getting piles of letters asking for some sort of closure to this cliffhanger, so this week we’re going to conclude the decade with the masterpiece of masterpieces, the coup de grace of the whole shmeer, “Kind of Blue”.

How good is this album? A few quotes:

How good is this album? A few quotes:

Duane Allman: “I haven’t hardly listened to anything else for the last couple of years.”

Chick Corea: “It’s one thing to just play a tune, or play a program of music, but it’s another thing to practically create a new language of music.”

Hip hop artist and rapper Q-Tip: “It’s like the Bible—you just have one in your house.”

US House of Representatives: “A national treasure.”

But my favorite appraisal is from critic Robert Palmer (liner notes from a remastered re-release):

[For music fans and critics] “no ‘great work’ is sacrosanct. Not all rock aficionados share a high opinion of Sgt. Pepper; to some, it’s uneven, self-indulgent, overproduced, underwritten—and dated.” But “Kind of Blue” is unique, he says. It has no detractors.

It’s universally acknowledged to be a masterpiece. By rockers, by rappers, by jazzists, by aficionados and snobs, by layfolk and casual listeners. By those of wooden ears. By elevator riders. It’s the prettiest background music you’ll ever not listen to. But if you do, it’s a monolith of lyric beauty and depth.

It’s universally acknowledged to be a masterpiece. By rockers, by rappers, by jazzists, by aficionados and snobs, by layfolk and casual listeners. By those of wooden ears. By elevator riders. It’s the prettiest background music you’ll ever not listen to. But if you do, it’s a monolith of lyric beauty and depth.

It is perfect.

It is so subtle, so nuanced, that you can listen to it several trillion times (as many have) with it sounding wholly fresh and vital every time. Ask Q-Tip.

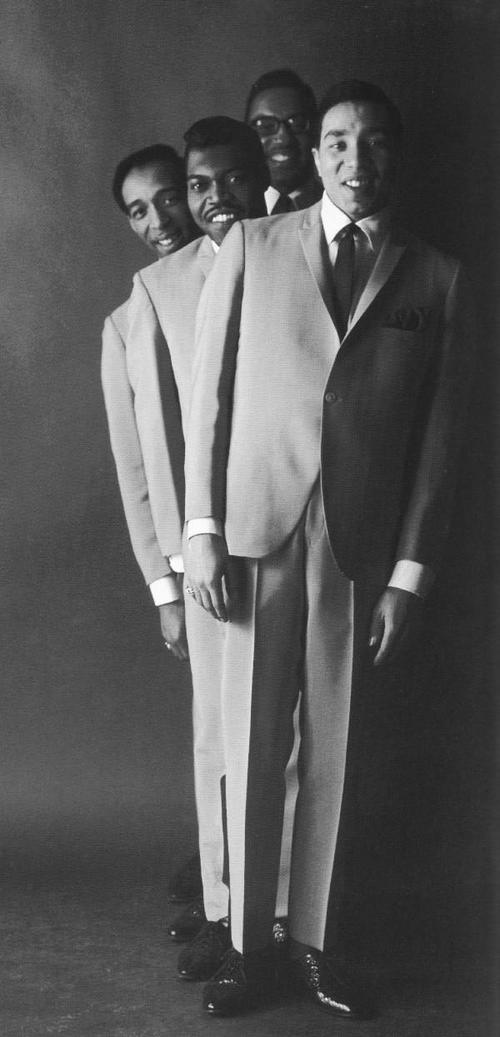

Miles’ 1955 quintet was still playing in the throes of post bebop, complex, dense, chord-laden music, which Miles now labeled “thick”. His band was falling apart, due to a fatal mix of drugs and ego. Pianist Red Garland went his way. Drummer Philly Joe Jones was grooving in his own vein. John Coltrane was bounced from the band for abuse and unreliability. While Miles was in France, Coltrane served a tour of duty with Thelonious Monk and got himself clean. Miles returned, rehired all three in addition to new-on-the-scene alto sax Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, recording with them the experimental album “Milestones,” and then fired the drummer and pianist. So we’re left with Miles on trumpet, Coltrane on tenor, Cannonball on alto, and good old Paul Chambers on bass. Jimmy Cobb came in on drums.

Via Gil Evans, Miles had read and been deeply influenced by a book called “The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization”, which posited an entirely new approach to what notes are played. It created Modal jazz. Jazz prior to this had been based on chord changes. Modal music talked about playing within a scale, free of the fetters of chords. The artist improvises melody, without the strictures of the over-evolved, ‘thick’ post-bebop music. Think of Peggy Lee’s ‘Fever’. No chords, just a series of modulating scales. Miles:

“No chords … gives you a lot more freedom and space to hear things. When you go this way, you can go on forever. You don’t have to worry about changes and you can do more with the [melody] line. It becomes a challenge to see how melodically innovative you can be. When you’re based on chords, you know at the end of 32 bars that the chords have run out and there’s nothing to do but repeat what you’ve just done—with variations. I think a movement in jazz is beginning away from the conventional string of chords… there will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them.”

“No chords … gives you a lot more freedom and space to hear things. When you go this way, you can go on forever. You don’t have to worry about changes and you can do more with the [melody] line. It becomes a challenge to see how melodically innovative you can be. When you’re based on chords, you know at the end of 32 bars that the chords have run out and there’s nothing to do but repeat what you’ve just done—with variations. I think a movement in jazz is beginning away from the conventional string of chords… there will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them.”

Okay, that may be a bit dry for a lot of normal people. But listen to this! “The Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization” was written by George Russell, a 25-year old black drummer who was hospitalized in 1945 for 16 months with tuberculosis. To wile away the time, he wrote this theoretical work. Gil Evans turned all the cool young musicians onto it. So now, in 1958, Miles asked George Russell to recommend a pianist who could play this modal stuff. (Russell had just finished recording a jazz concept album/composition entitled “New York, N.Y.” Participating in the session were Art Farmer, Bob Brookmeyer, Hal McKusick, John Coltrane, Milt Hinton, Barry Galbraith, Jon Hendricks, Phil Woods, Al Cohn, Max Roach, and Benny Golson, Oh, yeah, and a young honky pianist named Bill Evans.) Russell:

I recommended Bill.

I recommended Bill.

“Is he white?” asked Miles.

“Yeah,” I replied.

“Does he wear glasses?”

“Yeah.”

“I know that motherfucker. I heard him at Birdland—he can play his ass off. Bring him over to the Colony in Brooklyn on Thursday night.”

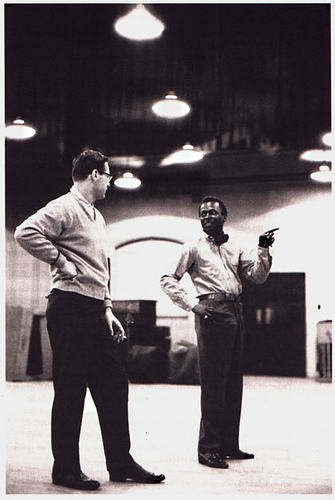

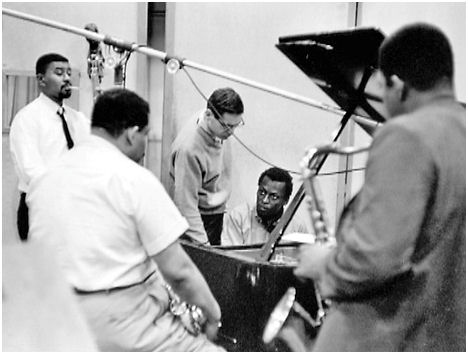

The club was in Bedford Stuyvesant, a neighborhood whites didn’t ordinarily enter. But George and Bill did, Bill sat in and got his white ass hired, and the classically-trained wimp became the pianist for the coolest jazz band in the world. Miles:

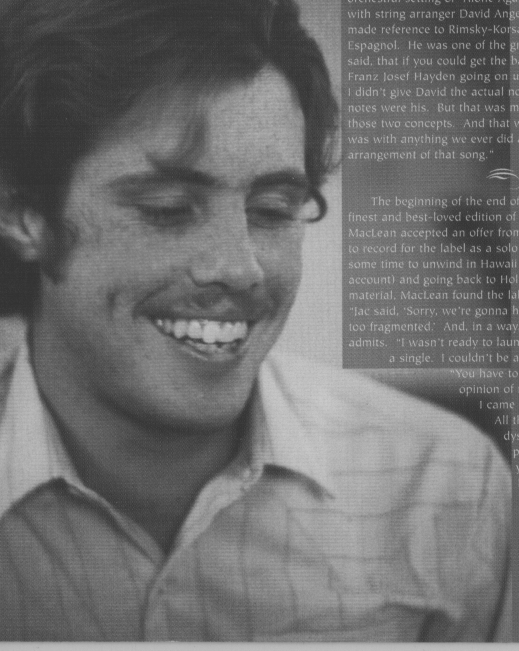

When Bill Evans—we sometimes called him Moe—first got with the band, he was so quiet, man. One day, just to see what he could do, I told him [and you have to hear Miles’ raspy whisper to really appreciate this], “Bill, you know what you have to do, don’t you, to be in this band?”

He looked at me all puzzled and shit and shook his head and said, “No, Miles, what do I have to do?”

I said, “Bill, now you know we all brothers and shit and everybody’s in this thing together and so what I came up with for you is that you got to make it with everybody, you know what I mean? You got to fuck the band.” Now, I was kidding, but Bill was real serious, like Trane.

He thought about it for about fifteen minutes and then came back and told me, “Miles, I thought about what you said and I just can’t do it, I just can’t do that. I’d like to please everyone and make everyone happy here, but I just can’t do that.”

I looked at him and smiled and said, “My man!” And then he knew I was teasing.

Bill brought a great knowledge of classical music, people like Rachmaninoff and Ravel. He was the one who told me to listen to the Italian pianist Arturo Michelangeli, so I did and fell in love with his playing. Bill had this quiet fire that I loved on piano. The way he approached it, the sound he got was like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall. I had to change the way the band sounded again for Bill’s style by playing different tunes, softer ones at first. Bill played underneath the rhythm and I liked that, the way he played scales with the band. Red’s playing had carried the rhythm but Bill underplayed it and for what I was doing now with the modal thing, I liked what Bill was doing better.

This Miles Davis sextet played standards and material from “Milestones” through most of 1958 without making any significant recordings. Miles:

Some of the things that caused Bill to leave the band hurt me, like that shit some black people put on him about being a white boy in our band. Many blacks felt that since I had the top small group in jazz and was paying the most money that I should have a black piano player. Now, I don’t go for that kind of shit; I have always wanted just the best players in my group and I don’t care about whether they’re black, white, blue, red or yellow. As long as they can play what I want that’s it. But I know this stuff got up under Bill’s skin and made him feel bad. Bill was a very sensitive person, it didn’t take much to set him off.”

Bill wanted desperately to please everybody and to fit in. So although he didn’t actually service the guys, what he did learn during that time was how to shoot heroin. After seven months, he’d had it with the road. He was replaced in the band by the very competent if uninspired blues-oriented pianist Wynton Kelly. In March, 1959, Miles brought Evans back for a couple of recording sessions. Wynton was the sitting pianist in the group—Miles liked to do that, to set one band member near another, to get them nervous. Fun guy, that Miles Davis.

Only hours before the session, Miles wrote down some sketches and taught them to the musicians during the sessions themselves. No rehearsals. Here’s the modal framework, go. Five songs for release in six takes.

Only hours before the session, Miles wrote down some sketches and taught them to the musicians during the sessions themselves. No rehearsals. Here’s the modal framework, go. Five songs for release in six takes.

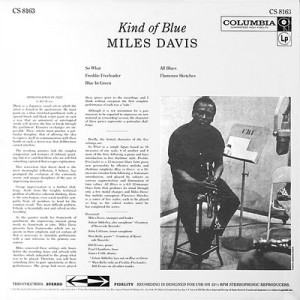

The very eloquent Bill Evans, from the original liner notes of “Kind of Blue” (you’ll pardon me for the extensive quote, but I have read these words hundreds of times, and find them an unplumbable source of wisdom and inspiration):

“There is a Japanese visual art in which the artist is forced to be spontaneous. He must paint on a thin stretched parchment with a special brush and black water paint in such a way that an unnatural or interrupted stroke will destroy the line or break through the parchment. Erasures or changes are impossible. These artists must practice a particular discipline, that of allowing the idea to express itself in communication with their hands in such a direct way that deliberation cannot interfere.

The resulting pictures lack the complex composition and textures of ordinary painting, but it is said that those who see well find something captured that escapes explanation.

The resulting pictures lack the complex composition and textures of ordinary painting, but it is said that those who see well find something captured that escapes explanation.

This conviction that direct deed is the most meaningful reflections, I believe, has prompted the evolution of the extremely severe and unique disciplines of the jazz or improvising musician.

Group improvisation is a further challenge. Aside from the weighty technical problem of collective coherent thinking, there is the very human, even social need for sympathy from all members to bend for the common result. This most difficult problem, I think, is beautifully met and solved on this recording.

As the painter needs his framework of parchment, the improvising musical group needs its framework in time. Miles Davis presents here frameworks which are exquisite in their simplicity and yet contain all that is necessary to stimulate performance with sure reference to the primary conception.

Miles conceived these settings only hours before the recording dates and arrived with sketches which indicated to the group what was to be played. Therefore, you will hear something close to pure spontaneity in these performances. The group had never played these pieces prior to the recordings and I think without exception the first complete performance of each was a “take.”

I’m not going to wax poetic here trying to replicate in mere words the beauty that is “Kind of Blue.” If you want to read more about it, Ashley Kahn wrote an entire book called “The Making of ‘Kind of Blue’“. But if you don’t own the album, you really should. Remember what Q-Tip said? One phrase of the first song on the album, ‘So What’, is worth a thousand words. The entire song is worth a book. The album is worth a library. It’s an education in itself. And if, as one assumes, you do own the album, give it a spin. It will sound as fresh as it always does. And thanks be to He Who Created jazz musicians for instilling in these six guys the talent to create such magical beauty. Humans creating perfection. Not something you run into everyday.

Thanks Jeff. One of my favourites…..

Nicely done. Tackling this monolith took courage. Never realized the album was done in one take like that. Essence of music, really. Thanks for the fine work.

I love the history……. it adds so much more to the already familiar music……. as always, amazing work Jeff

Mucho thanks. Good to hear from you.

As always you’ve given me background that simply opens the door to deeper understanding and appreciation. Oh, and it just so happens that it took me exactly 9:25 to read the post. I like that, too.

Thank you very much for your time and will to do that splendid and vivid history tales , you’re like one of the “Holly Word Messenger” leaving for generations the relation about those magnificent moments when the “creation of this Masterwork” was being doing for the “Jazz Gospel”, really cheers for do that titanic job!!!.

Thank you very much for that!!!

Kind of Blue is my favorite record ever! that silky trumpet gives me goosebumps every time.

“Jazz music has always been a place where anything is possible.” Bill Evans

Thank you for your beautiful exploration of what they made possible.

It’s a snowy, blustery day in Boston, a perfect time to pull out one of my six copies of the greatest jazz ever put to vinyl, boil a kettle, and let my pup know she’ll have to wait another hour or so for her next walk. Who knows – perhaps she’ll be seduced by Miles and his peerless, swingin’ cohorts along with this cozy fire I’ve got going. Or lulled into contented slumber by Jimmy Cobb’s holy grail ride cymbal…