Miles Davis Nonet–‘Move‘

Miles Davis Nonet–‘Move‘

Miles Davis Nonet–‘Jeru‘

Miles Davis Nonet–‘Israel‘

Les Double Six–‘Boplicity‘ (here’s a whole post on their music)

Mark Murphy–‘Boplicity‘

This week we’re going to make our first stop in a planned series following Miles Davis’ remarkable voyage through the 1950s.

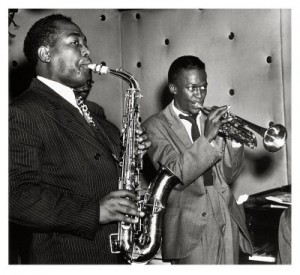

Let’s take 1947 as our starting point, when the WWII swing bands were dropping like brontosauri (all the young folk who had frequented clubs were staying at home nights parenting us baby-boom babies). The music that was thriving on 52nd street was bebop–fast, frenetic, insolent, wild and witty, indulgent, brilliant, and not to be danced to! Charlie (Bird) Parker (b 1920) was The Man whose music and life epitomized freedom – loose, unconstrained abandon.

Let’s take 1947 as our starting point, when the WWII swing bands were dropping like brontosauri (all the young folk who had frequented clubs were staying at home nights parenting us baby-boom babies). The music that was thriving on 52nd street was bebop–fast, frenetic, insolent, wild and witty, indulgent, brilliant, and not to be danced to! Charlie (Bird) Parker (b 1920) was The Man whose music and life epitomized freedom – loose, unconstrained abandon.

Miles Davis (b 1926) was raised in the very bourgeois home of a St Louis dentist who owned horses. Much to his father’s chagrin, he took to jazz trumpet. A tender 18-year old in 1944, he joined the traveling Billy Eckstine big band in which Bird was playing alto sax. When they finally landed in New York, Charlie wanted to rebuild his old bebop quintet (here on film with his old playmate Dizzy Gillespie). But Diz refused to play with him any more because of Bird’s impossibly dissolute lifestyle, so Bird gave young Miles his big break.

Miles was never the greatest trumpeter around. He had very limited technique, so he stuck to playing select notes in the middle register of his trumpet simply because he couldn’t play as fast or as high as many of his contemporaries. Bird apparently didn’t mind, and Miles was happy to be in the company of the most renowned jazz musician of the era. Throughout the two years he played with Bird, Miles stayed clear of drugs and booze (though not of women). But Bird’s penchant for damaging himself and those around him was as great as his genius as a musician, and Miles left him in 1949.

Miles was never the greatest trumpeter around. He had very limited technique, so he stuck to playing select notes in the middle register of his trumpet simply because he couldn’t play as fast or as high as many of his contemporaries. Bird apparently didn’t mind, and Miles was happy to be in the company of the most renowned jazz musician of the era. Throughout the two years he played with Bird, Miles stayed clear of drugs and booze (though not of women). But Bird’s penchant for damaging himself and those around him was as great as his genius as a musician, and Miles left him in 1949.

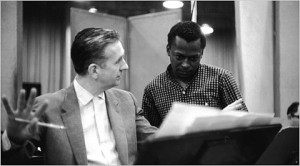

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Claude Thornhill was a dinosaur in the post-WWII years, maintaining a Swing-era style dance band whose distinguishing style was slow, dreamy ballads. Gil Evans (b 1912), wanted to write an arrangement of a Bird song for Thornhill, and approached Miles to get some help with the charts. So began a legendary partnership. Here’s Bird’s version of “Anthropology”, here’s Gil Evans’ arrangement.

In 1948, Miles was hanging out with a group of young musicians at Gil Evans’ apartment behind a Chinese laundry. They exchanged ideas and played together informally. Evans was the guru, Miles was the driving force, but the music was a group effort according to the many accounts. They played a couple of gigs opening for Count Basie, and recorded 12 sides. They were so insignificant commercially that they had no real name (The Miles Davis Group, The Miles Davis Nonet, The Miles Davis Tuba Band). But over the years this effort became a legend, known as The Birth of the Cool.

In 1948, Miles was hanging out with a group of young musicians at Gil Evans’ apartment behind a Chinese laundry. They exchanged ideas and played together informally. Evans was the guru, Miles was the driving force, but the music was a group effort according to the many accounts. They played a couple of gigs opening for Count Basie, and recorded 12 sides. They were so insignificant commercially that they had no real name (The Miles Davis Group, The Miles Davis Nonet, The Miles Davis Tuba Band). But over the years this effort became a legend, known as The Birth of the Cool.

The 12 cuts recorded in 3 sessions in 1949 were originally released as 78 RPM singles; 8 of them were released on a 10″ record in 1954, 11 of them on a 12″ LP in 1957 under the name “Birth of the Cool”. Numerous versions have been released since. In 1998 they were released together with the (inferior) live performances, called “The Complete Birth of the Cool”. In recent years, Gerry Mulligan created a “The Rebirth of the Cool” group; the reconstructed scores were released in book form; and bands and combos all over the world play the charts regularly.

Miles Davis was an angry young man. He fought with police and the white music business establishment. In the early 1950s he displayed angry Black Pride almost a generation before that mindset gained wide currency. And yet, paradoxically, his great music from the 1950s was sweet, poignant, romantic, a monumental marriage of the black jazz tradition with white European music.

Miles Davis was an angry young man. He fought with police and the white music business establishment. In the early 1950s he displayed angry Black Pride almost a generation before that mindset gained wide currency. And yet, paradoxically, his great music from the 1950s was sweet, poignant, romantic, a monumental marriage of the black jazz tradition with white European music.

I don’t know how to explain that. Critics don’t address the subject very much. But the music, all agree, is heavenly. It’s also commonly called ‘pivotal’ and ‘seminal’, because it pretty much single-handedly established Cool Jazz–the predominant mindset of modern jazz.

Miles (and Evans) used a nonet for these recordings–trumpet, trombone, French horn, tuba, alto sax, baritone sax, piano, bass and drums. (as opposed to the typical bebop quintet or swing band of at least 16 musicians). The use of French horn and a tuba for tonal breadth was unique in jazz, the latter employed for the first time not as a bass/rhythm instrument, but as a melodic one. In reaction to both bebop and swing, the sound they created displayed a light, vibratoless tonality, subtle rhythm, pure tone, legato phrasing. They stressed the seamless integration of scored sections with improvised elements.

Miles (and Evans) used a nonet for these recordings–trumpet, trombone, French horn, tuba, alto sax, baritone sax, piano, bass and drums. (as opposed to the typical bebop quintet or swing band of at least 16 musicians). The use of French horn and a tuba for tonal breadth was unique in jazz, the latter employed for the first time not as a bass/rhythm instrument, but as a melodic one. In reaction to both bebop and swing, the sound they created displayed a light, vibratoless tonality, subtle rhythm, pure tone, legato phrasing. They stressed the seamless integration of scored sections with improvised elements.

The song we’ve chosen from the collection is “Boplicity”, written by Miles (under his mother’s maiden name, Cleo Henry) and Evans (uncredited), arranged by Evans. Solos are (in order) by Mulligan (baritone sax), Miles, and John Lewis (piano).

The influence of these 1948 recordings cannot be overstated. Gerry Mulligan soon split for California (a la Jack Kerouac), forming there a pianoless quartet with young Chet Baker and starting the first school of white jazz, West Coast cool. John Lewis formed the Modern Jazz Quartet. Lee Konitz, the only musician participating in all three recording sessions, is one of my very favorite musicians. He had a magnificently varied career stretching from his first solo with Claude Thornhill in 1947 up till his death during the pandemic at age 92.

The influence of these 1948 recordings cannot be overstated. Gerry Mulligan soon split for California (a la Jack Kerouac), forming there a pianoless quartet with young Chet Baker and starting the first school of white jazz, West Coast cool. John Lewis formed the Modern Jazz Quartet. Lee Konitz, the only musician participating in all three recording sessions, is one of my very favorite musicians. He had a magnificently varied career stretching from his first solo with Claude Thornhill in 1947 up till his death during the pandemic at age 92.

Miles had already begun dabbling in heroin at this time, and would soon sink into a 3-year abyss. But he would go cold turkey on his father’s horse farm and return to form his first quintet (with young John Coltrane), and record 2 masterpieces in collaboration with Gil Evans (‘Porgy and Bess’ and ‘Sketches of Spain’) and one of the great albums of modern music, ‘Kind of Blue’–all before the decade was out.

But we get ahead of ourselves. Let’s just pause for a moment here and treat ourselves to 2’58” of heaven.

What a great and interesting post.

I might hazard a statement that Miles’ lack of pyrotechnics in his playing is what made him the man he became. ie Cool.

His ‘less is more’ style was actually what held him apart from the others.

Even Wynton Marsalis started by trying to sound like Miles.

There are many trumpet players with superior technique to Miles but would you dare to compare Oscar Peterson to a more minimalist Bill Evans?

Nevertheless a great and interesting post. Lets have more.