Charles Ives, ‘The Unanswered Question’ (Bernstein/NYPO)

Charles Ives, ‘The Unanswered Question’ (Bernstein/NYPO)

Charles Ives, ‘Central Park in the Dark’ (Bernstein/NYPO)

Charles Ives, ‘Concord Sonata’ Movement 2 (The Alcotts)

I have a self-imposed rule for Song of The Week: “Write about music you love with a passion.” This week I’m breaking that rule.

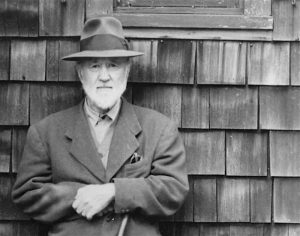

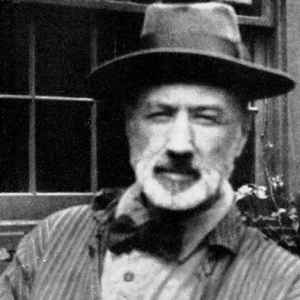

I do not love the music of Charles Ives, but I admire the man passionately. He’s my new role model – despite (or probably because of) the fact that his life was a paragon of a trait I painfully lack.

During the work week, Charles Ives (no relation to Burl) founded one of the most successful insurance companies in the US, invented the concept of estate planning, and wrote crazy, impossible music on the commuter train and on weekends. His music was largely ignored during his lifetime—and he didn’t give a flying hoot.

Me? I dabble in quasi-creative enterprises and when the world doesn’t collectively lie down on its back in reverence I run home crying. This is a guy I have to learn from.

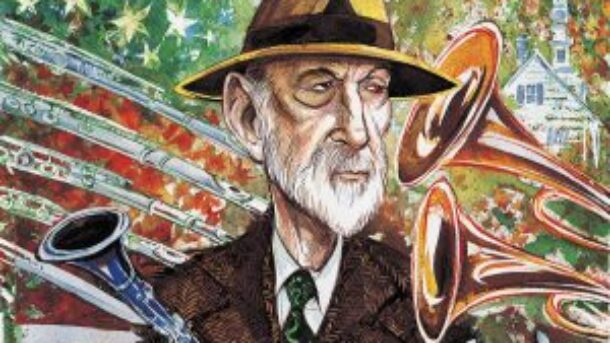

Charles Ives Ives (1874 – 1954) was an American modernist composer, experimenting in atonality before Schoenberg and in free dissonance before Stravinsky. His roots were the church and band and popular and folk music of Danbury, Connecticut. His musical education (at Yale) was in the classical European tradition.

His mentor, inspiration and guiding light was his father, George, who led ‘the best band in the Union army’ during the Civil War. When he caught his 5-year old son banging out the rhythm part of a band piece on the piano with his fists, he patted the boy on the head and sent him for drum lessons. Charles later became one of the first proponents of cluster chords, instructing the pianist in one of his most famous compositions, the Concord Sonata, to use a board 14 3/4 “ long to play them.

His mentor, inspiration and guiding light was his father, George, who led ‘the best band in the Union army’ during the Civil War. When he caught his 5-year old son banging out the rhythm part of a band piece on the piano with his fists, he patted the boy on the head and sent him for drum lessons. Charles later became one of the first proponents of cluster chords, instructing the pianist in one of his most famous compositions, the Concord Sonata, to use a board 14 3/4 “ long to play them.

George Ives would have his son sing in one key while he accompanied in another; he built instruments to play quarter-tones; he played his cornet over a pond so Charlie could gauge the effect of space; he set two bands marching around a park blaring different tunes, to see what it sounded like when they approached and passed. Of a man singing off-key in church: “Look into his face and hear the music of the ages. Don’t pay too much attention to the sounds–for if you do, you may miss the music. You won’t get a wild, heroic ride to heaven on pretty little sounds.”

Charles was a professional church organist at the age of 14, already composing pieces considered difficult to play even today, which Charlie called “as much fun as playing baseball”. He moved to New Haven, captained his high school baseball team, was touted as a potential champion sprinter, joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, and learned all the rules he was determined to flaunt under the leading teacher of the European classical tradition in America.

Charles was a professional church organist at the age of 14, already composing pieces considered difficult to play even today, which Charlie called “as much fun as playing baseball”. He moved to New Haven, captained his high school baseball team, was touted as a potential champion sprinter, joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity, and learned all the rules he was determined to flaunt under the leading teacher of the European classical tradition in America.

He left Yale in 1898 to work in the insurance business in New York. As he put it, if a composer “has a nice wife and some nice children, how can he let them starve on his dissonances?”

From 1906-08 his various lives climaxed.

He founded the insurance company which he would build into an empire until his retirement in 1930.

He suffered his first breakdown.

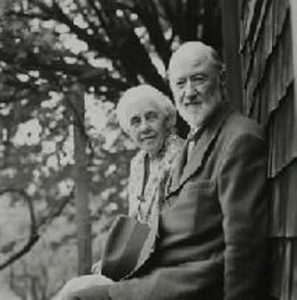

He married Harmony Twitchell, a fellow Transcendentalist (followers of the thoughts of Emerson and Thoreau).

And he composed prolifically (on the commuter train and on Sundays), including “Two Contemplations”: “Central Park in the Dark” and our SoTW, “The Unanswered Question”. Both pieces would wait until 1946 for their first performance.

“Central Park in the Dark” was originally titled “A Contemplation of Nothing Serious or Central Park in the Dark in ‘The Good Old Summer Time’”. He described it thus: “This piece purports to be a picture-in-sounds of the sounds of nature and of happenings that men would hear some thirty or so years ago (before the combustion engine and radio monopolized the earth and air), when sitting on a bench in Central Park on a hot summer night.”

“Central Park in the Dark” was originally titled “A Contemplation of Nothing Serious or Central Park in the Dark in ‘The Good Old Summer Time’”. He described it thus: “This piece purports to be a picture-in-sounds of the sounds of nature and of happenings that men would hear some thirty or so years ago (before the combustion engine and radio monopolized the earth and air), when sitting on a bench in Central Park on a hot summer night.”

“The Unanswered Question” is scored for 3 voices playing in independent tempos. A string quartet placed offstage! sustains slow tonal triads that according to Ives represent “The Silence of the Druids—who Know, See and Hear Nothing”. The solo trumpet presents a nontonal phrase seven times—”The Perennial Question of Existence”, which a quartet of flutes answers in increasing frustration six times. They are “Fighting Answerers” who, after a time, “realize a futility and begin to mock ‘The Question'” before finally disappearing, leaving “The Question” to be asked once more before “The Silences” are left to their “Undisturbed Solitude”. The seventh ‘question’ of the trumpet is left unanswered by the flutes.

“The Unanswered Question” is scored for 3 voices playing in independent tempos. A string quartet placed offstage! sustains slow tonal triads that according to Ives represent “The Silence of the Druids—who Know, See and Hear Nothing”. The solo trumpet presents a nontonal phrase seven times—”The Perennial Question of Existence”, which a quartet of flutes answers in increasing frustration six times. They are “Fighting Answerers” who, after a time, “realize a futility and begin to mock ‘The Question'” before finally disappearing, leaving “The Question” to be asked once more before “The Silences” are left to their “Undisturbed Solitude”. The seventh ‘question’ of the trumpet is left unanswered by the flutes.

Leonard Bernstein called these “the beginning of American music”.

Over the next decade, Ives composed furiously, including his major works. In 1918, the same year he published his groundbreaking “Life Insurance with Relation to Inheritance Tax”, he suffered his second breakdown, after which he composed very little, although he continued to revise earlier works. One day in early 1927 Ives came downstairs with tears in his eyes. He could compose no more, he said, “nothing sounds right.”

He would spend the rest of his life revising, organizing and self-publishing his own compositions, as well as anonymously supporting other modernist composers. But his music went unperformed until 1939, when a recital of the “Concord Sonata” garnered rave reviews. In 1947 Ives was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in music for his Symphony No. 3, completed nearly 40 years earlier.

In 1951, Leonard Bernstein and his New York Philharmonic premiered Ives’ “Second Symphony”. Although he offered Ives to conduct a private performance for him in a darkened hall, Ives refused to attend. A few days later, when the symphony was broadcast, he went into the kitchen to listen to it on the maid’s radio. From the liner notes of the LP: “He emerged from the kitchen doing an awkward little jig of pleasure and vindication. This seems to have been the only unqualified pleasure in an orchestra performance that Ives ever had.”

His reputation has since grown exponentially, his works being canonized by Leonard Bernstein as those of a “true primitive”, an “authentic American saint… Americans found Mark Twain, Emerson and Abraham Lincoln all rolled into one.” His proponents eventually included Mahler, Stokowski, Tilson Thomas, Frank Zappa, and Phil Lesh, bassist of the Grateful Dead (“One of my two musical heroes”).

Arnold Schoenberg: “There is a great Man living in this Country – a composer. He has solved the problem how to preserve one’s self-esteem and to learn. He responds to negligence by contempt. He is not forced to accept praise or blame. His name is Ives.”

“He responds to negligence by contempt.” I’ve been thinking a lot about that lately. When people ask me “What do you do?” I mumble something about my history of day jobs, and add “but mostly I am involved with music.” “Oh, you have a hobby?” they respond, smiling condescendingly.

After Wallace Stevens won the Pulitzer Prize for his poetry in 1955, he was offered a faculty position at Harvard but declined since it would have required him to give up his vice-presidency of The Hartford. Was his poetry a ‘hobby’?

In his twenties, Tenessee Williams worked at the International Shoe Company factory, then later as a caretaker on a chicken ranch. His mother:”Tom would go to his room with black coffee and cigarettes and I would hear the typewriter clicking away at night in the silent house. Some mornings when I walked in to wake him for work, I would find him sprawled fully dressed across the bed, too tired to remove his clothes.” Were his plays a ‘hobby’?

In his twenties, Tenessee Williams worked at the International Shoe Company factory, then later as a caretaker on a chicken ranch. His mother:”Tom would go to his room with black coffee and cigarettes and I would hear the typewriter clicking away at night in the silent house. Some mornings when I walked in to wake him for work, I would find him sprawled fully dressed across the bed, too tired to remove his clothes.” Were his plays a ‘hobby’?

Jazz pianist Denny Zeitlin (b. 1938) has 35 albums and piles of awards to his credit. He was also clinical professor of psychiatry the University of San Francisco. Was his music a ‘hobby’?

Minimalist composer Philip Glass worked as a plumber and a taxi driver. Glass was called to the house of art critic Robert Hughes to install a dishwasher. Hughes recognized him and complained that Glass was an artist, and therefore shouldn’t be installing a dishwasher. Glass replied that yes, he was an artist, but he was sometimes a plumber as well, and Hughes should go away and let him finish the job. Were his compositions a ‘hobby’?

These gents achieved recognition in their lifetimes. So we retrospectively minimize their day jobs, right? Charles Ives only began to taste acknowledgement at the very end of his life, but is today canonized, and good for him.

These gents achieved recognition in their lifetimes. So we retrospectively minimize their day jobs, right? Charles Ives only began to taste acknowledgement at the very end of his life, but is today canonized, and good for him.

What makes these people legitimate ‘artists’, their belated public recognition? What about the forgotten Franz Kafkas and Emily Dickinsons? – the innumerable unrecognized, great artists who labored at their crafts nights and weekends and train rides, year after year, decade after decade, only to have their executors eventually dump the contents of their desk drawers into the garbage bin? What about the myriads of honest, dedicated pedestrian practitioners who supported their families by day and toiled in their chosen medium with passion at night as “amateurs”–literally, ‘lovers’?

To all the honest, unrecognized or insufficiently appreciated practitioners of creative endeavors, myself included, I wish you a modicum of Charles Ives’ dignity. May you–correct that, may we–respond to negligence with contempt. Well, we’re not all Charles Ives, so may we at least temper the lack of appreciation with the knowledge that we had the passion and conviction of our creation. Charlie Ives knew that that’s what really matters.

A thoughtful tribute to Ives, and the many other ‘amateurs’ that enrich our world.

Even without the celebrity, you are doing that as well. Thanks so much.

I really appreciate this- as a 20 year old who loves art and has many passions, I feel a lot of pressure (from myself) to be “successful” and the best, and it’s nice reading stories of artists who were so casual and personal with their art. I have to remind myself why I do it often to not get overwhelmed, but it’s a struggle. Reading this definitely helped relieve some of the pressure though, thank you!

An interesting, no, a great SotW to remind us of the importance of art. Not success or recognition or steady income, if we do it as a passion, but as a means of expression that enriches our lives. As for Charles Ives, I love the way his father supported his musical journey. In a way, that’s true American pioneer spirit!

Pretty interesting. At first, you made him seem to be a superman. Then we started hearing about his mental problems. I wonder if they are related.