Alchemy 101: Take a jazz banjoist, a classical double-bassist and a percussionist of traditional Indian music, mix vigorously, and waddaya get? “The Melody of Rhythm”. Oh, yeah, and if you’re feeling really rambunctious, or perverse, just for fun you can also toss in the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under the baton of maestro Leonard Slatkin.

Let’s see if we can demystify that, or at least demist it.

Let’s see if we can demystify that, or at least demist it.

Like so many other New York kids, Béla Fleck (b. 1958) got turned onto the banjo by (snore) ‘Dueling Banjos‘ from the film “Deliverance”, where a city slicker plays acoustic guitar behind the front-porch banjo of an Appalachian backwoods idiot savant kid, before the latter’s uncle rapes the city guy just for fun.

That very famous clip is a Hollywoodized taste of bluegrass, which is a folk music from those mountains, popularized in the 1940s and 1950s by Bill Monroe and Earl Flatt & Lester Scruggs. Arising from Scottish-Irish roots, traditional bluegrass is typically based on a small set of acoustic stringed instruments including mandolin, acoustic guitar, banjo, fiddle, dobro and upright bass. Note the absence of drums.

In the 1970s and northwards, some stellar musicians such as Jerry Garcia, David Grisman, Andy Statman and Tony Rice played a lot of second generation bluegrass. Then in the 1980s a newer aesthetic began to evolve from these roots, progressive bluegrass or ‘newgrass’, led by Mr Fleck himself. These musicians retained the original orchestration of bluegrass, but incorporated a jazz-based musicality, resulting in a wonderfully unclassifiable new sub-genre with its own very loyal cadre of followers and an active festival circuit. Bela’s home base for the past 30 years has been his own band The Flecktones, who have made tons of innovative, marvelous music, but he’s also been involved in heaps of transient projects with a number of recurring partners, one of whom is Edgar Meyer, with whom he’s been fiddling around for 25 years.

In the 1970s and northwards, some stellar musicians such as Jerry Garcia, David Grisman, Andy Statman and Tony Rice played a lot of second generation bluegrass. Then in the 1980s a newer aesthetic began to evolve from these roots, progressive bluegrass or ‘newgrass’, led by Mr Fleck himself. These musicians retained the original orchestration of bluegrass, but incorporated a jazz-based musicality, resulting in a wonderfully unclassifiable new sub-genre with its own very loyal cadre of followers and an active festival circuit. Bela’s home base for the past 30 years has been his own band The Flecktones, who have made tons of innovative, marvelous music, but he’s also been involved in heaps of transient projects with a number of recurring partners, one of whom is Edgar Meyer, with whom he’s been fiddling around for 25 years.

Jazz/classical/newgrass bassist Meyer (b. 1960) hails from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, received his classical training at Indiana, and in 2002 was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, “The Genius Award”, the neatest recognition bestowed on humans. Edgar has recorded in more contexts than would seem possible – Bach’s cello suites on bass; a solo album playing piano, double bass, guitar, banjo, viola da gamba, mandolin and dobro; the Coplandian Grammy-winning “Appalachian Journey” and “Appalachian Waltz”, collaborations with Yo Yo Ma and newgrass fiddler Mark O’Connor, a rare case of respectable ‘classical crossover’; and several knockout concerti of his own composition recorded with symphony orchestras, one for double bass, one for double bass and cello (played by good old Yo Yo), one for banjo (guess who) and double bass, and a triple concerto for double bass, banjo and tabla that you just might read about below.

Jazz/classical/newgrass bassist Meyer (b. 1960) hails from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, received his classical training at Indiana, and in 2002 was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, “The Genius Award”, the neatest recognition bestowed on humans. Edgar has recorded in more contexts than would seem possible – Bach’s cello suites on bass; a solo album playing piano, double bass, guitar, banjo, viola da gamba, mandolin and dobro; the Coplandian Grammy-winning “Appalachian Journey” and “Appalachian Waltz”, collaborations with Yo Yo Ma and newgrass fiddler Mark O’Connor, a rare case of respectable ‘classical crossover’; and several knockout concerti of his own composition recorded with symphony orchestras, one for double bass, one for double bass and cello (played by good old Yo Yo), one for banjo (guess who) and double bass, and a triple concerto for double bass, banjo and tabla that you just might read about below.

Zakir Hussain (Hindi: ज़ाकिर हुसैन, Urdu: ذاکِر حسین, in case you were wondering) was born in 1951 in Mumbai, son of the legendary tabla player Alla Rakha. Zakir was a child prodigy on the tabla, moved to the US in 1970 and began playing with the likes of George Harrison, John McLaughlin, Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead, and Bela Fleck and Edgar Meyer. This was much to the chagrin of his father, who refused to condone this newfangled stuff until Zakir promised him that he would never stop playing traditional Indian music. I really don’t get what was bugging dad, who had himself appeared alongside Ravi Shankar (Norah Jones’ father) at the Monterey and Woodstock festivals, as well as recording an album with Buddy Rich! But Dad had some stature. Mickey Hart: “Allarakha is the Einstein, the Picasso; he is the highest form of rhythmic development on this planet.” The tabla, for the uninitiated amongst you, “involves extensive use of the fingers and palms in various configurations to create a wide variety of different sounds, reflected in the mnemonic syllables (bol). The heel of the hand is used to apply pressure or in a sliding motion on the larger drum so that the pitch is changed during the sound’s decay.” That may not sound too intriguing, but just listen to how Zakir says it. Convinced, are you?

Zakir Hussain (Hindi: ज़ाकिर हुसैन, Urdu: ذاکِر حسین, in case you were wondering) was born in 1951 in Mumbai, son of the legendary tabla player Alla Rakha. Zakir was a child prodigy on the tabla, moved to the US in 1970 and began playing with the likes of George Harrison, John McLaughlin, Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead, and Bela Fleck and Edgar Meyer. This was much to the chagrin of his father, who refused to condone this newfangled stuff until Zakir promised him that he would never stop playing traditional Indian music. I really don’t get what was bugging dad, who had himself appeared alongside Ravi Shankar (Norah Jones’ father) at the Monterey and Woodstock festivals, as well as recording an album with Buddy Rich! But Dad had some stature. Mickey Hart: “Allarakha is the Einstein, the Picasso; he is the highest form of rhythmic development on this planet.” The tabla, for the uninitiated amongst you, “involves extensive use of the fingers and palms in various configurations to create a wide variety of different sounds, reflected in the mnemonic syllables (bol). The heel of the hand is used to apply pressure or in a sliding motion on the larger drum so that the pitch is changed during the sound’s decay.” That may not sound too intriguing, but just listen to how Zakir says it. Convinced, are you?

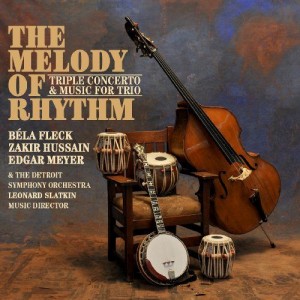

So these three guys get together in 2009 – sort of like a centaur, a mermaid, and a Toyota Prius in a ménage a trois – and record an album called “The Melody of Rhythm.”

There are nine cuts on the CD, the middle three being the aforementioned Triple Concerto. Thom Jurek, the most effusive music writer around, calls it a “spacious, wide-ranging, beautifully paced concerto with the trio interacting on its own quite intently and with the DSO not as individual instrumentalists, but as a group in dialogue with the orchestra [in a mix of] jazz, Indian folk forms, classical music, Appalachian folk, progressive instrumental music.”

The first and last three pieces on the CD are just our three guys creating something wholly other – unique, transcending taxonomy like nothing else you’ve ever heard, as natural and organic as a single petal of a daisy, unforced, convincing and absolutely lovely. Here you are, our SoTW, ‘Babar’, the first cut from “The Melody of Rhythm”. Indeed.

The first and last three pieces on the CD are just our three guys creating something wholly other – unique, transcending taxonomy like nothing else you’ve ever heard, as natural and organic as a single petal of a daisy, unforced, convincing and absolutely lovely. Here you are, our SoTW, ‘Babar’, the first cut from “The Melody of Rhythm”. Indeed.

For your further listening edification:

There are lots of YouTube clips of the trio performing live, all of problematic audio quality. Here’s a nice NPR article on the them with some links of better quality.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy these off-beat recommendations:

068: Hermeto Pascoal, ‘Santa Catarina’

063: Pust, ‘En Reell Halling’

030: The Bulgarian State Radio and Television Women’s Choir (Le Mystere des Voix Bulgares) – ‘Pilentze Pee’

003: Garcia/Grisman, ‘So What’

Mikey likes it. Wow!

Like everything thing Bela touches, this stuff is gold! Thanks for turning me on to this.

I’m guessing that he’s the Prius in your analogy?

One thing I learned in literature school, take a metaphor only as far as it works.

I always enjoy your Song of the Week but don’t always comment as I don’t usually have anything intelligent to add. I feel compelled to respond here as I’ve quite simply never heard anything like this music. I love the cultural mix. Thanks for broadening my horizons!

נהנתי מאוד,תודה ושבת שלום

The bass solo at the intro of “Babar” is simply delicious.

I could swear that’s a sitar, and not a banjo…..

Beautiful.

I always enjoy your Song of the Week but don’t always comment as I don’t usually have anything intelligent to add. I feel compelled to respond here as I’ve quite simply never heard anything like this music. I love the cultural mix. Thanks for broadening my horizons!

Thanks for this. Love it!

Thanks for this. Love it!

Beautiful! Always been a fan of Bela Fleck, and LESTER Flatt & EARL Scruggs 🙂

I always enjoy your Song of the Week but don’t always comment as I don’t usually have anything intelligent to add. I feel compelled to respond here as I’ve quite simply never heard anything like this music. I love the cultural mix. Thanks for broadening my horizons!

Many thanks this time.

Has no one ever heard of Ralph Towner’s group, Oregon??? I suggest their album “Distant Hills.” This was fusion music before its time.

Ach! Another CD I will need to buy. Thank you, JM, for helping me to keep the right priorities.