Dylan just turned 82, and the dude shows no signs of slowing down.

I wrote the following piece during the Nobel controversy. I talk about The Basement Tapes, about how much Dylan has informed and affected me for 60 years, and attempt to express just how I perceive him as an artist.

It’s a longish read, but, fuck, it’s Bob Dylan. Respect, man.

You Ain’t Going Nowhere

Too Much of Nothing

Quinn, the Eskimo

Nothing Was Delivered

Well, Bobby, you done it. Pulled another rabbit out of your illusionist’s top hat. The master of sleight of word has once again danced the dance of the seven veils and come out fully clothed, masked and smirking.

Folks are all a-buzz, and that’s great. The more people buzz about Bob, the better the world. A bunch of SoTW readers have said they expect me to weigh in, so here goes my 2¢.

Disclaimer

I’m going to step on some toes here. (Howie/Shmuel, I love you, but I’m gonna be speaking my mind here, not The World’s.)

I’m going to talk about my relationship with Bob.

Let me clarify that. Most people who write or talk about Dylan passionately want to explain him to you. I once saw a TV show in which a bunch of local artists each presented “My Dylan”. I was sick in bed for two weeks. My Dylan? What is he, a catcher’s mitt? An aquarium?

They don’t own him, any more than you own your child, any more than you own the wind. He owns himself. I have no My Dylan. He baffles me. He befuddles me. He eludes me, deludes me, precludes me, secludes me, fastfoods me…

I don’t own Dylan, I don’t possess him. Hell, I don’t even grasp him.

The most I can do is to try to describe how I perceive him, shade it with some biographical or socio-historical hues, season it with a bit of humor. But if you’re looking for the key, that’s not me. You can find it in the Nobel-worthy John Wesley Harding liner notes: ‘The key is Frank.’

I offer you as a foil My James Taylor.

James began sharing his most intimate thoughts and feelings with me when we were 20, and they have been a balm for me ever since. I embrace him in my mind, in my heart. I’d love to go fishing with him.

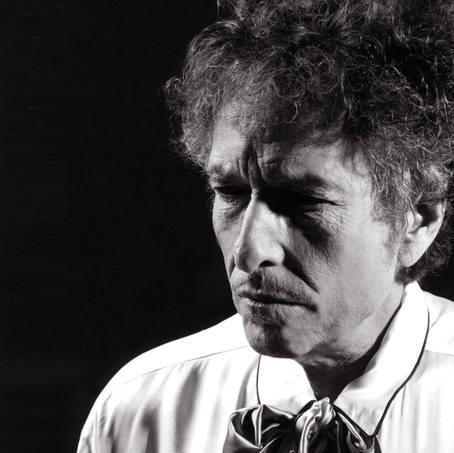

Not so Mr Dylan. He has informed me, stirred me, enlarged me, served me as a model for emulation. But I wouldn’t go up to him and hug him. The one time I did meet him, in his dressing room backstage at The Johnny Cash Show, May 1, 1969, I had the opportunity. I didn’t hug him. I stuttered.

“Hi. I’d like to talk to you.”

“About what?”

“About music.”

“I don’t know much about music.”

The fleeting moment of Dylan intersecting with my real world.

My Perception of Dylan

I’m guessing that 98% of the people voicing their thoughts about Dylan receiving the prize will talk about him still growing strong at 75. I’m in the 2%. I just listened to 20 seconds of him at Desert Trip, 10 of McCartney and 5 of The Stones. That’s way more than too much for me.

Dylan earned my vote for what he did 50 years ago. I choose to ignore these old farts’ pathetic attempts to stay relevant (and rich). My respect is for them in their prime, not in their dotage.

What I talk about when I talk about Dylan

His great works:

- Freewheeling (1963)

- The Times They Are A-Changing (1964)

- Another Side Of (1964)

- Bringing It All Back Home (1965)

- Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

- Blonde on Blonde (1966)

- The Basement Tapes (1967)

- John Wesley Harding (1967)

- New Morning (1970)

- Blood on the Tracks (NY sessions, 1975)

- Desire (1976)

- A couple of handsful of assorted songs.

I’m not including his admirable-but-less-than-great works, because they obfuscate matters: Nashville Skyline (1970), Planet Waves (1974), Oh Mercy (1989), Time Out of Mind (1997), Love and Theft (2001), and Modern Times (2006).

I’m also not including a whole gaggle of stuff I have great admiration for, which reflect Dylan at his finest, but are outside the scope of his primary achievement, his songs: various liner notes (especially Bringing It All Back Home and John Wesley Harding), Chronicles, his satellite-radio show Theme Time Radio Hour.

Is Dylan eligible for the Nobel Prize in Literature?

A former secretary of the Nobel Committee told me that the judges adhere meticulously to the letter and spirit of Alfred Nobel’s last will and testament. But I checked, and Al’s will doesn’t specify what constitutes ‘literature’. “…One part to the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction.” Al invented dynamite, and was sharp enough to appoint experts to choose the laureates. ‘The prize shall be awarded by the Academy in Stockholm.’

What is “Literature”? Winston Churchill was an orator. Last year’s laureate was Svetlana Alexievich, a Belarusian investigative journalist whose written corpus consists of interviews. No one made a peep, not even in Belarusian.

Haruki Murakami was considered a leading candidate. I’ve read a number of his books, and I’d put money on him saying something like ‘Dylan’s a million times more worthy than I of the prize’. Haruki is a fine writer, and he sounds like a guy I’d want to hang out with over a couple of beers. We’d probably talk about Dylan. In my most Dylanesque dreams, I couldn’t envision myself schmoozing with Bob over a brew, talking about Murakami.

Leonard Cohen’s reaction: “It’s like pinning a medal on Mount Everest for being the highest mountain.”

In other words, the prize is nice, it’s cute, but it’s not validating. Dylan doesn’t need anyone’s validation.

Does Dylan write poetry?

Answer #1:

No.

He writes lyrics to songs that he sings.

But he publishes his lyrics as written words!

So did Harold Pinter. You can buy the script of a Bergman movie.

Dylan’s defining mode of expression is singing songs. The lyrics and the music and the arrangement and the performance are all part of his artistic gestalt.

Answer #2:

I’m no expert on the subject, although I do have a couple of academic degrees in poetry, and I’ve been following Dylan closely for about 52 years, so I guess I ought to be able to say something coherent on the subject.

Unfortunately, I can’t. The question of whether Dylan’s lyrics stand as ‘poetry’ is one I’ve never really been interested in addressing. It’s speculation, it’s moot, it’s irrelevant.

It’s no more reasonable to judge his lyrics as poetry than it is to set Shakespeare’s sonnets to music and to judge them as lyrics.

Old Willie Yeats hit it on the head: O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,/How can we know the dancer from the dance?

Is Dylan worthy of The Nobel?

Dylan made his initial mark as a protest singer. I’m not even going to put that in quotation marks. It was his first persona, singing ‘Blowing in the Wind’ and ‘Masters of War’ and ‘With God on Our Side’ with Joan Baez and marching with Martin Luther King (August, 1963). But by January 1964 (liner notes to “The Times They Are A-Changing”) he was singing a different tune:

Woody Guthrie was my last idol/he was the last idol/because he was the first idol/I’d ever met/face t’ face/that men are men/shatterin’ even himself/as an idol/an’ that men have reasons/for what they do/an’ what they say/an’ every action can be questioned/leavin’ no command/untouched an’ took for granted/obeyed an’ bowed down to/forgettin’ your own natural instincts/(for there’re a million reasons/in the world/an’ a million instincts/runnin’ wild/an’ it’s none too many times/the two shall meet)/the unseen idols create the fear/an’ trample hope when busted/Woody never made me fear/and he didn’t trample any hopes/for he just carried a book of Man/an’ gave it t’ me t’ read awhile/an’ from it I learned my greatest lesson/ /you ask “how does it feel t’ be an idol?”/it’d be silly of me t’ answer, wouldn’t it . . .?

And by August, 1964, we were listening to another side of Bob Dylan: Good and bad, I define these terms/Quite clear, no doubt, somehow./Ah, but I was so much older then,/I’m younger than that now.

That was the first life lesson I learned via Dylan. Not from him, but through him. I was only 16 when he recorded and I heard ‘My Back Pages’. I had my pantheon of heroes—John & Paul, and John Keats, I guess. Preceded by Mickey Mantle and The Lone Ranger. Succeeded by Hitchcock and Primo Levi and Oliver Sacks and Rav Soloveitchik and JS Bach. In 1964, at 16, Dylan was my idol. And he’s telling me that there ain’t no idols. So that was a bit confusing. But most everything is confusing for a 16-year old, and Dylan is confusing for adults. Like in 1974, when he finally released a live album with The Band, and it was so bad, his shouting a parody of a drunken, tone-deaf fraternity boy shouting out the lyrics. Or 1980, when he espoused a belief in Christianity. Dylan, the brightest of all, was spouting patent poppycock.

First he told me that there are no idols. Then he demonstrated it to me.

I always lagged behind Dylan, for a myriad of reasons. One of them is that he’s seven years older than me. I really encountered Dylan seriously in 1964, with “Another Side Of”. I was in the 10th grade. He was 23. That’s a big difference. I didn’t have 23-year old friends then, obviously. He was writing songs like ‘All I Really Want to Do’, the most disingenuous seduction song I know.

I’m guessing that at 16 I took it at face value, hearing the same theme as The Beatles’ ‘I’m Happy Just to Dance with You’, which was released the very same month. (If you’re wondering why Dylan got the Nobel and not the Beatles, there’s your answer. Sixteen year-old Jeff had no trouble palling around with them.) Or the rich, impassioned love/hate songs ‘I Don’t Believe You’ (I can’t understand, she let go of my hand) and ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe’ (Go ‘way from my window, leave at your own chosen speed.) How could I grasp those songs at 16? I’d barely been kissed.

And so it went, over the decades. So many songs just took me years to digest, to intuit, to get close to. I started to say ‘to wrap my mind around’, but that’s not really true. ‘All Along the Watchtower’ or ‘As I Went Out One Morning’–I fail to comprehend (that’s denotation as ‘wrap your brain around’) as much today as I did at 19, when “John Wesley Harding” was released. I’ve learned to accept their mystery, to love it. That’s where Dylan’s energy is, his electricity. In the synapses between what he says and what I understand.

What has Bob Dylan been for me? (And again, let me stress how different that question is from ‘Who is Bob Dylan in my eyes?’.)

Prophet?

I’m very uncomfortable with that term. No, he’s a human, directed not by the word of God, but by his own imagination. I’d maintain that there’s a fundamental connection between God and Dylan’s imaginative capacity, but Isaiah and Jeremiah made their reputations on the distinction between themselves and God, not by the overlap.

From the git-go, Dylan has been a man not of answers, but of questions. The answer is blowing in the wind.

Teacher?

I’ve certainly learned through him. But he’s never stood up in front of me and said ‘Open your book to page 61’ or ‘Spit out the gum’ or ‘You have to listen to this’. And I never asked him for permission to go to the john. All three times I saw him, I bought a ticket and he sang some songs.

“Myself, what I’m going to do is rent Town Hall and put about thirty Western Union boys on the bill. I mean, then there’ll really be some messages.”

Role model?

Role model?

I’ve never sneered at a former girlfriend ‘How does it feel to be on your own?’. I’ve never flirted with Christianity. I’ve never been painted in white-face, sported a pencil moustache, or uncovered Sinatra.

Bob Dylan writes songs about what he sees and thinks and feels. I listen to them, form my impression of them, and go my merry way. More often than not, they give me food for thought. They enlighten me, because I learn things about the world through his eyes.

As he said in his later years about Woody Guthrie, “You could listen to that music and learn how to live.” There’s a big difference between that an idolatry. The learning is on the listener.

You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.

Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters.

The pump don’t work ‘cause the vandals took the handles.

Music like that that played an instrumental, formative role in my learning how to live – to the extent that I’ve done so.

The Basement Tapes

In July, 1966 (shortly after the release of “Blonde on Blonde”), Dylan had a motorcycle accident and disappeared from the public eye. In December, 1967, he released the somber, enigmatic, cryptic “John Wesley Harding”, full of biblical allusions and newly-coined myth.

In July, 1966 (shortly after the release of “Blonde on Blonde”), Dylan had a motorcycle accident and disappeared from the public eye. In December, 1967, he released the somber, enigmatic, cryptic “John Wesley Harding”, full of biblical allusions and newly-coined myth.

I ingested the album immediately – acoustic, soft and gentle in texture, profound and ominous in content. I’m still working on wrapping my mind around it, because that’s what I do. I know I’ll never be any wiser for all the effort, at least not in this lifetime.

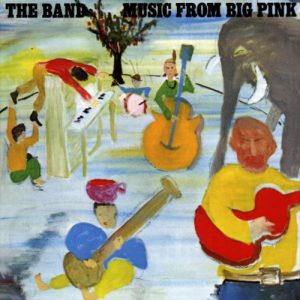

We didn’t know it back then, because there were no alternative media resources, no Rolling Stone, no interweb, but Dylan recorded “John Wesley Harding” during a short break from his main occupation of the summer of 1967. He was hanging out with The Band in the basement of Big Pink, making music, old and new. Garth had a tape recorder.

A few pieces leaked out, but we couldn’t put them together: Peter Paul and Mary’s ‘Too Much of Nothing’ (September, 1967); Manfred Mann’s ‘Quinn the Eskimo’ (January, 1968), and most importantly “Music from Big Pink” in June, 1968, containing ‘Tears of Rage’, ‘This Wheel’s on Fire’ and ‘I Shall Be Released’. In November, 1968, The reconstituted Byrds released the first country-rock album, “Sweetheart of the Rodeo”, including ‘Nothing Was Delivered’ and ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere’.

Each one was an inscrutable, Sphinx-like enigma, although together with “John Wesley Harding”, some sort of picture was beginning to emerge – something homesy, acoustic, grounded, back to basics. There was sublime humor (‘I looked at my watch, I looked at my wrist, I punched myself in the face with my fist’) and profound anguish (‘Any day now, any day now, I shall be released’).

“Nashville Skyline”, released in April, 1969, just made things confusinger.

Jeff the Bootlegger

But sometime in the winter I took a trip up to that town of refuge for bohemians, Yellow Springs, home of Antioch College, and came back with some paradigm-shifting booty: “The Great White Wonder” and “Troubled Troubadour”— unofficial, illegal vinyl recordings of the Basement Tapes and a few other unreleased Dylan oldies–the very first bootleg albums.

But sometime in the winter I took a trip up to that town of refuge for bohemians, Yellow Springs, home of Antioch College, and came back with some paradigm-shifting booty: “The Great White Wonder” and “Troubled Troubadour”— unofficial, illegal vinyl recordings of the Basement Tapes and a few other unreleased Dylan oldies–the very first bootleg albums.

Years later I would organize the best of these recordings onto a cassette that I played till it plopped. I called the cassette “Never Felt So Good”, which can be read in several very different ways. The music reflected both.

The Up Side was a series of hilarious verbal tours de force – Yeah, Heavy and a Bottle of Bread; Million Dollar Bash; Tiny Montgomery; Lo and Behold; Please, Mrs Henry.

The Down Side contained several Scary Clown cuts (Nothing Was Delivered, Quinn the Eskimo, Too Much of Nothing), and several songs so serious, so profound, so rich that they continue today to shake and touch me to the very core–Tears of Rage, This Wheel’s on Fire, I Shall Be Released.

There was one cut that was too serious for The Up Side, too funny for The Down Side. Just like life. To even out the cassette, ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere’ went on the shorter side.

Clouds so swift rain won’t lift, gate won’t close and the railings froze

Get your mind off wintertime, you ain’t goin’ nowhere.(chorus)

Whoo-ee! Ride me high, tomorrow’s the day my bride’s gonna come.

Oh, oh, are we gonna fly down in the easy chair!

I don’t care how many letters they sent, morning came and morning went.

Pack up your money and pick up your tent, you ain’t goin’ nowhere

Buy me a flute and a gun that shoots, tailgates and substitutes.

Strap yourself to a tree with roots, you ain’t goin’ nowhere.

Genghis Khan, he could not keep all his kings supplied with sleep.

We’ll climb that hill no matter how steep when we get up to it

That’s Dylan for me. Elusive, slippery. Riveting. Hilarious and harrowing. You could listen to that music and learn how to live.

The Best of Times, The Worst of Times

But my mind was busy rocking and rolling at that time. I’d mark ‘that time’ from the release of “John Wesley Harding” (December 1968) till May, 1970, 18 months.

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us…

It was the headiest of times. Musically, it was the golden age of our lifetimes. Politically, the war was raging and the draft was a horrifying specter. Personally, I was having the time of my life. Hell, it was Woodstock! It was the apex of “The 60s” – sex, drugs and rock-and-roll dangling from every lovely low branch.

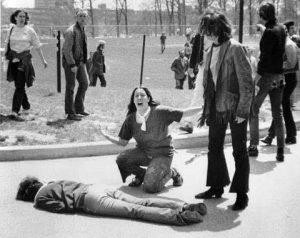

Then on May 4, 1970, the National Guard opened fire on protesting students at nearby Kent State, and it all came crashing down.

Then on May 4, 1970, the National Guard opened fire on protesting students at nearby Kent State, and it all came crashing down.

The university closed down, and every single familiar, friendly face in my life disappeared into the woodwork. My parents had left town half a year before. I was unmoored. Lost, disillusioned, terrified. Freefall.

Suddenly, I was rudderless, depressed and desperate. I did something unconscionably reckless, and paid for it with a 24-hour living nightmare. The next day, my sister was in town to visit her in-laws. I sat in the front seat of my car with her, held her perfect, innocent 10-month old baby in my arms, and wept.

I said, “I don’t like the life I’m leading. That’s not me.”

But what was me? I had no clue. Like always, I turned to the jukebox in my head for an answer. Do you know what came on?

“Strap yourself to a tree with roots, you ain’t going nowhere.”

Within six months I was engaged to a rigorously clear-minded and focused woman, had moved to a fledgling country whose very existence was still precarious, and had committed to a religiously observant life.

The Meshel

Am I thrilled by Dylan’s being awarded The Nobel? As my father used to say, it’s better than a sharp stick in the eye. But, no, The Nobel is nothing more than a nice-to-have.

Am I thrilled by Dylan’s being awarded The Nobel? As my father used to say, it’s better than a sharp stick in the eye. But, no, The Nobel is nothing more than a nice-to-have.

Almost 50 years ago, in my heart and soul and mind and life, I bestowed an award on this artist for introducing me to a new direction, a path I chose to adapt and adopt and live by. So today, let’s make it public and formal:

I hereby pronounce you, Robert Allen Zimmerman, aka Bob Dylan, the recipient of The Meshel, for creating music that has had a profoundly formative impact on my life.

Don’t ever stop writing, Jeff. You just make my DAY!!

Thank you for your observations and personal experience with Dylan’s music. As a novice Dylan listener, I appreciate the insight and also the way you write about the profound way music can be interwoven into our lives. Thanks for a great post.

Thanks, guys.

Epic.

Dylan and this SoTw.

Both.

As good as always, both sotw and Dylan.

Beautiful, witty, sly, and profound, Jeff. Like you, I think.

I like a couple of BD songs that conjure memories of my past. I don’t use them to guide my life. I don’t think most people have used them to guide their

lives. I am a free thinker as well as a conservative Catholic. Deal with it. I have a happy-realistic life. I am fairly practical. So I am results oriented. The

results of the whole folk movement, in its many iterations, is TODAY. We have a deeply flawed impostor president in power who desperately requires

removal by a deeply flawed orange man. The sooner the better. Jeff, you write well. You think YOU. My hobby is music and you keep that alive. Thanks.

I will always love the way you write. The exception: the use of the “f ” word. Really necessary? Your vocabulary is too large in English and Hebrew. Great songs but my favorite will always remain ‘Dream” performed by PP&M

When I was in high school (Class of ’66), someone asked the English teacher “Is Bob Dylan a poet?”

The teacher said, “Of course Bob Dylan is a poet. He’s a bad poet.”

I’ve got to agree. When Dylan’s far-flung net hauls a rhyme in, sometimes it’s fine serendipity and sometimes it’s just embarrassing.

Very interesting insight into the impact that Dylan had on you. He is an amazing writer/poet and I think he speaks to many now as he has for many years.