I relate to the world through music. If you follow this blog, I’m guessing you’ve figured that out. What music to listen to, that’s my existential focal point.

Thirty-five days ago my family suffered a pogrom, when thousands of Hamas terrorists broke through the border fence between Gaza and Israel, murdered 1400 innocent people, commiting unspeakable atrocities and war crimes.

For a week, my ears couldn’t tolerate any music, no matter how grave. Not even Bach’s cello suites, Bill Evans solo, nor the Swedish folk’apella Kongero—my A-list for deep mourning music.

On October 7 it was my family that was decimated. I needed Israeli music. Like many Israelis, I turned to this grassroots lamentation, ‘Ein Li Eretz Aheret’ (SoTW 309).

Then I decided to force myself into motion. The first music I listened to was Poogy (the nickname of the band Kaveret). Why did I start with Poogy? Because theirs was the first music we listened to after the trauma of the Yom Kippur war, the first time we allowed ourselves to smile. Because of Danny Sanderson’s sad-funny Yiddish humor.

Post-pogrom humor.

Several days later I re-encountered the album in unspeakably horrifying circumstances. (SoTW 135)

Click on the photo on the right by Maya Oshri Meshel (my very talented daughter-in-law). It expresses my feelings better than I could in words.

There’s one other artist tagged in my heart as post-Yom Kippur War, Matti Caspi. I wrote about ‘Song of the Dove’ years before the October 7 pogrom, when it was still palatable to talk about peaceful co-existence. Well, I suppose I still believe in peace, in the abstract sense, but the song certainly doesn’t reflect my feelings right now. To every thing there is a season.

I’m floundering for music to listen to. I’ve been sorely neglectful of much Israeli music, including the “Religious Rock” sub-genre. Many of the songs are from the Jewish liturgy or psalms, sung in typically Jewish post-pogrom minor keys. Musical prayers of longing.

Longing for what, for peace? Seriously? Perhaps just for healing.

We Israelis can’t live without the hope for respite, for a resting place for Matti Caspi’s dove, for peace. For me right now, peace on earth is soaked in fresh blood. Perhaps there’s nothing left to do but to pray for some sort of peace we don’t understand to come from we know not where.

102: Netanela, ‘Shir HaYona’ (Matti Caspi)

I landed in Israel in 1970, twenty-two years old, carrying a passport from the Woodstock nation, Uncle Sam in hot pursuit to conscript me to Vietnam. I was carrying one suitcase of clothes (no winter coat) and one box of records (without which I wasn’t going anywhere).

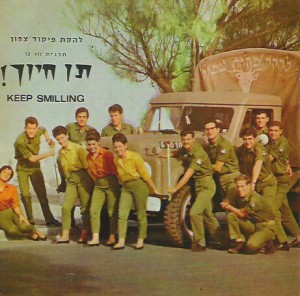

The music scene in my adopted country was as foreign to me as the backwards alphabet, the Bolshevik political climate and the Levantine cultural assumptions. The Big Deal in popular music back then in the interbellum years (1967–1973) was the army troupes.

The IDF (Israel Defense Force) was a civilian army. Everyone joined at eighteen, boys for three years, girls for two. They still do, actually. In those days, the IDF (Zahal in Hebrew) was at the center of the country’s mind, pocketbook, and Top 40. The dream of every young musician was to be accepted to an army entertainment troupe (lahaka tzvait), of which there were more than a dozen, and most of the future stars ascended through this farm system. Each comprised a dozen or more conscripts who would develop a program of songs composed and directed by the leading lights of Israel’s popular culture, and spent their service performing for the troops.

These programs were the heart and soul of Israel’s popular culture. The music was innocent, the frame of reference communal rather than personal. Here are a couple of clips from Lahakat HaNahal, “The Officer Forgave” (with very telling photos) and “Comradeship” (an archetypical expression of the Zahal ethos).

Musically, I felt like I had been exiled to Goth from Medici Florence – Dylan, The Band, Joni Mitchell, CSN&Y, Janis, Hendrix at the height of their creativity. So I bought myself a little Phillips record player (paying 120% tax) and spent a number of years avoiding the native music by hiding my head in my box of 40 albums.

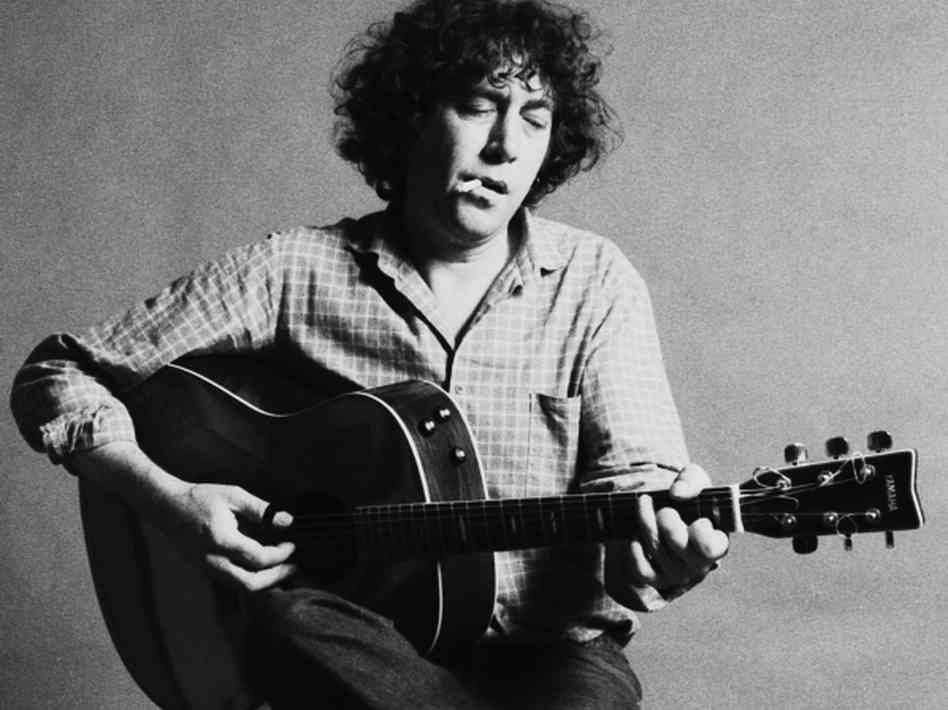

But then came the Yom Kippur War, with my new country tottering on the brink of extinction. In its wake, everything changed, including the music. The idealism of youth was shattered, and Israel began to awaken to the big world outside. Two new artists spoke to my ears in aesthetically mature and culturally engaging voices – Kaveret (Beehive) and Matti Caspi (b. 1949). His first two solo albums (1974, 1976) are still among my very favorites today.

Matti has travelled a long and bumpy road, musically and personally – an acrimonious divorce, self-imposed exile to Los Angeles, never reaching the same creative heights of those early albums. What has remained a constant is his sinuous, challenging, beautiful melodic and harmonic voice. You can invariably recognize a Caspi composition within a couple of bars. He’s primarily a composer (always using collaborators for lyrics). He’s a knock-out arranger (as our SoTW will show), a very honest and touching singer, an almost virtuoso multi-instrumentalist, and a terrific performer. He also has the driest sense of humor this side of the Sahara.

I really can’t do justice to the entirety of Matti Caspi’s large and varied corpus. Here’s one of my favorites, ‘How Dares the Star?‘ And another, ‘Here, Here’, using musical terminology to describe a song about a relationship. Here’s one of his most moving love songs, ‘Brit Olam‘ (Eternal Covenant). And here’s one of the funniest clips I’ve ever seen, ‘A Man Should Not Be Alone‘ (which also got its very own SoTW 150 all to itself, together with the Adam and Eve story). The text is from Gen 2:18. Matti was born and raised on a kibbutz, so he’s no stranger to the cowshed. Note the footwear. Towards the end, he says, ‘Kulam!’ (Everyone join in singing!).

In 1973 he was doing his reserve duty writing a program for the Air Force Troupe (my reserve duty, in contrast, usually consisted of planting mine fields—do you know how heavy anti-tank mines are?). There Matti (25) met Netanela (19), with the blackest hair on God’s earth, Uzbeki cheekbones and a timbre thicker than Nina Simone’s. Over the years he employed her voice as a unique color in his musical palette. Back then, a year before his first solo album, he composed a song based on lyrics by Shimrit Orr, ‘Shir HaYona’ (Song of the Dove):

Way up above the towers

The dove spreads her wing, gliding afar, her eyes longing.

High above like bell-clappers (sic!),

At daybreak she coos, and at nightfall is dumb, her wings alight.

Onwards, onwards, above the water she hovers, still waiting.

Way up above the Hills of Gilboa, above the clouds, the road is long.

The allusion, of course, is to Noah’s dove, searching for dry land. The dove holding the olive leaf in its beak is biblical. In early Christianity, the Hebrew ‘aleh’ was mistranslated as a branch–it really means ‘leaf’. As a symbol of the peace of the soul, the dove appears in 4th century Christian art. It referred to political peace as early as the 5th century, but was popularized by Picasso’s drawing La Colombe for the UN in 1949.

Matti orchestrated the song for a popular musical festival (when you watch the clip, remember that ‘music festival’ for me meant Woodstock), gave it to Netanela to sing, and the result was indelible. Here’s the memorable live performance; here’s the original recording (pay special attention to the beautiful orchestration). Here’s a lesser, later version of Matti and Netanela dueting on it.

Netanela also had her ups and downs personally and musically. She had several very fine hits (‘We Haven’t Discussed Love Yet’, ‘White Days’), mostly penned by Matti. Then she married a Swede and split her life between the North and the Middle East. Her career went off track, even though her version of ‘Eli, Eli’ was used in the final scene of the Israeli version of Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List”,(‘Jerusalem of Gold’, SoTW 282, was used abroad, but was too maudlin for the local audience). The words of ‘Eli, Eli’ (entitled ‘Walking to Ceasarea’) were written by 21-year old Hannah Senesh before she was parachuted as a Palestinian soldier by the British behind Nazi lines to try to save the Jews of her native Hungary. She was caught, tortured and killed. ‘Eli, Eli’ has become a secular Zionist prayer, obliquely pleading for the fundamental right to live freely. (My God, my God, may it never end, the sand and the water, the sound of the sea, the lightening in the sky, the prayer of man.) For a 21-year old Hungarian Jewess in 1942, that was an existential prayer.

‘Shir HaYona’ expresses a similar sentiment, a wish for transcendence, also a secular prayer. It struck a most responsive chord in the hearts of a people reeling from a national trauma, and gave voice to its deepest wish – to simply be left to lead a normal life in peace. In 1974, even though much of my musical tastes lay elsewhere, my heart was in Israel, recovering with everyone else from that national post-war shock, and this very beautiful song gave voice to that longing. I think the sentiment, and the song, are still very beautiful and truthful today.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy:

SoTW 150: Matti Caspi, ‘Not Good, A Man Being Alone’