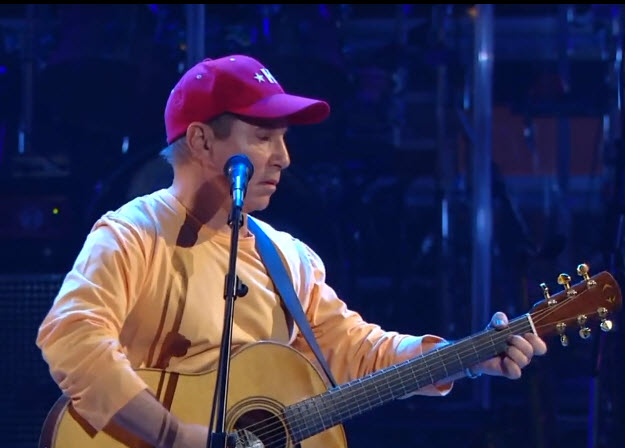

The fabulously talented pianist Omri Mor will appear at Zappa Tel Aviv on October 29 with his AndalouJazz trio. Not to be missed.

Listen to him live at the Red Sea Jazz Festival, 2010.

Here’s some more clips from that gig: TuesdayI TuesdayIIIsinger wedI you,night,music intro

Omri Mor may not yet be a household name, not even among jazz fans in New York or Paris. But he will be. In his native Israel, he’s already a legend among those in the know. He’s been the pianist in the trio of bassist Avishai Cohen (together with brilliant young drummer Amir Bressler) for a year now, globetrotting between festivals and clubs worldwide. A prestigious gig indeed, but his local reputation centers on his own trio project, a vibrant, exciting new style he calls AndalouJazz, Omri’s own creation, in which all three members contribute to a driving, polyrhythmic North African-tinged high-energy synthesis.

It’s jazz, drawing from all the traditional and contemporary vocabularies available, but the most singular musical inspiration for this Adaloujazz project is Nino Biton, a legendary figure in Jerusalem whose name is synonymous with ethnic Moroccan and Algerian music. He plays oud and violin, but is most famous as a paytan, a cantor of Sephardic liturgical poetry. Nino has also cast his spell over a cadre of young musicians who were fascinated by this traditional genre. Omri relates that he met Nino when he was only 14, and that Nino needed a keyboard player in his band to play the very complex Andalousian music. Omri says that he fell deeply in love with it, and for years has been going to Nino, sitting with him for hours at a time, sometimes playing music with him all night long. Nino never took money, Omri says, but is a great teacher in the traditional Moroccan sense.

Omri eventually got the idea to use Andalousian melodies as a basis for jazz improvisation, much as jazz musicians have traditionally done with American standards. In doing so, Omri avoids the pitfalls of crossover jazz, which usually results in music which is neither jazz nor the style it is trying to incorporate. Omri’s respect for this North African music is great, and the music is consequently honest, duly respectful, and inspired.

Omri’s background is Argentinean and Iraqi; bassist Simon Starr is an immigrant from Australia; drummer Noam David’s family originated in Spain and Iraq – a healthy Israeli mixed salad. But, as Omri says, no matter where your parents are from, in Israel you always come across Mizrachi (Israeli pop music with a high dosage of Middle Eastern influence) or Arabic music of different types. All three musicians are well-schooled in traditional American jazz, but this project is an innovative, riveting take on the traditional music of Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. “North African music (‘mashric’, east in Arabic) is very different from other styles of Arabic music (‘magrib’, west), says Omri.”It’s full of African polyrhythms, like 3/4 played over 4/4. The accented beat of the measure isn’t necessarily the first one, unlike Western or other Arabic music. Andalousian music often merges with Latin music as well, since North Africa was ruled by Spain, after all. So Andalousian music and Cuban music are related in many ways.”

The inspiration for the Omri Mor AndalouJazz Project may be North African, and they may be playing in what is ultimately an American idiom, but the mix is most decidedly Israeli. Regardless of the style they choose to play in, they are a highly-skilled, precisely honed jazz trio, what in the business is called ‘tight’.

Ever since I first heard the Omri Mor Trio at the Red Sea Jazz Festival in 2010, I’ve been revisiting these bootleg recordings, and my admiration for them just grows and grows – the electricity they generate is still palpable. We sat with Omri recently for an update.

He told me that he was flying to Paris the next day for a couple of gigs with Algerian drummer Karim Ziad, former drummer with Joe Zawinul, a leading name in North African ethnic music. They will be playing together with the Dialna ensemble (‘ours’ in Moroccan). In general, Omri’s been travelling a lot with Avishai, playing festivals all over the world. They’re out on tour a couple of times a month, which keeps him pretty busy. Even though the trio has been together for a year, they have rehearsals to polish things, to prepare new pieces for the repertoire.

Omri says it’s a great gig, that he greatly admires Avishai’s musicianship. Omri says that Avishai is real composer, which is crucial in jazz, that the artist be a composer as well as a player.

Asked to differentiate between his own trio’s music and Avishai’s, Omri says that Cohen’s music has a lot more Latin and Turkish elements in it, whereas his is more focused on North African rhythms, but that they’re both very Mediterranean, very Israeli.

Omri mentions that he’s been studying classical piano with his teacher Shoshana Cohen for years, and practices a lot, which also keeps him busy. He’s not actively exploring new styles of music because he feels like he has more to do in his AndalouJazz. He says that when he feels that he’s finished his work there, he’ll explore new styles.

Asked about the current trio, Omri says that the new bassist, Simon Starr, is an Australian, living in Israel, that he plays Andalousian music with an Aussie accent, and that they need to pour some ‘arisa’ on him. However the drummer, Noam David, doesn’t need any more spicing up – he’s got plenty.

I say that one thing I’ve always found unique about his trio is how percussive it all is, home much of a joint effort it is, how central the beat is. Omri responds that he likes to lean on the beat, to work with the drummer, that he always tries to stimulate the rhythm, to create a piano/drum dialog.

I ask him if he listens a lot to other musicians, to which he responds that he doesn’t when he’s in a creative period, that he needs his energy for his own music. What about at festivals, I ask? You must be exposed to a lot of other artists. Omri says that before he goes on stage he’s preparing himself mentally, and afterwards he’s too tired.

Asked if he still spends time with Nino Biton, he says that he still goes to him to play music, talk, and even drink a bit.

I ask Omri if he’s never tempted to play a slow romantic standard, rubato, free of the very rhythmic music he usually plays. Every good melody has its internal pulse, he answers, with it’s own inner rhythm. The length of every note creates a rhythm. Rhythm is everywhere—it’s in the melody, in the harmony, in the movement of the chords. The etymology of the word rhythm is ‘flow’. [I checked, he’s right.] The music has to flow, he says.

More please, sir!

We want more!

Hello! Where can I get a cd of the AndalouJazz Project? Its very good.

Maayan, it a great shame, but Omri hasn’t recorded any of this yet. There are a few things on YouTube, both as a trio and as a quintet. IMHO, the clips posted above are the best I’ve heard.

Thanks, Jeff! Omri is a wonderful piano man & I love his style. Be it his rhythms, be it his way of playing “wide harmony” arpeggios. Great stuff.