‘You Will Walk in the Field’, Chava Alberstein (1975)

‘You Will Walk in the Field’, post-October 7 pogrom ensemble (2023)

‘You Will Walk in the Field’, Chava Alberstein (2013, live)

‘You Will Walk in the Field’, Shlomi Saranga (2008)

‘You Will Walk in the Field’, Rona Kenan (2021)

I don’t know how we’re going to feel after this war in Gaza. My only point of reference is how we felt after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. I remember the pain, the sorrow, the communal depression. The years-long struggle to return to “normal”.

There are striking similarities and great differences between that war and the October 7 pogrom. In both, Israelis were shocked into inspiring cohesiveness and resilience, the entire nation clutching each other like an organic family, together shedding mixed tears of sorrow and joy.

If you’ve been following my post-pogrom Songs of The Week, you may have noticed that they’re all Israeli. I find myself able to listen only to music in Hebrew. I guess it’s a tribal thing—circle the wagons. This week, even as we struggle to function ‘normally’, I’ve been immersing myself in a uniquely Israeli genre—Memorial Music.

Israel is usually perceived as as an active, vital, vivacious nation. That’s true, but think how often our country is couched in mourning. Every few months we have our Holocaust Day, or Memorial Day, or 9th of Av, or the day before Yom Kippur. And nary a season goes by without a major terrorist attack. For all of those days, there’s no happy music on the radio.

But you can’t just stop playing music, people need the balm. So DJs and memorial ceremony organizers reach for the Memorial Music playlists. I don’t know what the key is—how many dead Jews trigger a programming change and for how long. But we know the drill well.

That adds up to a lot of quiet, introspective music. Over the last hundred years, Jews have displayed a noteworthy penchant for creating quality popular music (Gershwin, Dylan, etc.). Being that young Israeli musicians are also Members of that Tribe, it’s no surprise that Memorial Music has grown into a highly-evolved genre, some of Israel’s finest popular music.

The genre of Memorial Music flowered in the wake of the Yom Kippur War, and has continued to grow since. ‘I Have No Other Land’ (SoTW 309) is from 1986, as is ‘Ashes and Dirt’ (SoTW 310). But still today on the various days of mourning, you’ll hear a disproportionate amount of mid-70s music. Perhaps because that war was our greatest national shock, jarring loose creative juices. Perhaps there were just a bunch of fine artists all trying to deal with our national post-bellum blues–Arik Einstein (SoTW 184), Kaveret (SoTW 135), Shlomo Artzi, Matti Caspi (SoTW 102). Perhaps these were the first generation of fine young Sabra mourning songs, and they’ve become the template, the classics. In any case, they’re still all over the radio today.

Even teenagers sitting around a bonfire with a guitar, drinking wine, hormones pulsing—together with today’s raucous rock you’re likely to hear them singing these tender, poignant songs of reflection. They’re affectionately referred to as ‘Shirei Dikaon’, ‘Depression Songs’. This is our culture, such is our life.

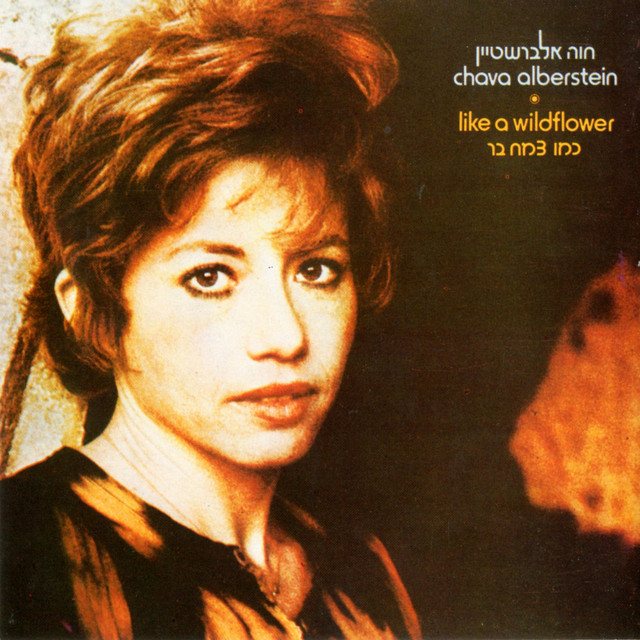

Chava Alberstein (b. 1946) is the queen of Memorial Music. In the throes of the Yom Kippur War she recorded the album “Like a Wildflower” to express “the need to turn the frustration, the humiliation, and the pain we all felt after the Yom Kippur War into something positive, changing, hopeful. I felt a need to comfort, not to shout, not to accuse. The songs on this album found each other like people finding soulmates in a crowd.”

Since the mid-1970s, her songs have become more than popular—they’re post-trauma national icons.

One of the best is ‘You’ll Walk in the Field’ (‘At Tilchi baSadeh’). The lyric is a poem by Leah Goldberg, born into a Lithuanian family in 1911. She got a PhD from the Universities of Berlin and Bonn and mastered many European languages. But she was a poet and a Zionist, and vowed to write only in Hebrew. At 15, she wrote in her diary “The unfavorable condition of the Hebrew writer is no secret to me. Writing in a different language than Hebrew is the same to me as not writing at all.”

She immigrated to Palestine in 1935, leaving behind the center of European culture for a non-state desert wasteland with a Jewish population of under 400,000, sworn to write only in a language which had been dead for 1600 years and was disinterred and reawakened only 50 years earlier. A brand-new language still in ancient diapers, in which through sheer will and determination she composed indelible poetry still relevant today.

In ‘You’ll Walk in the Field’ the narrator describes a woman walking barefoot through a freshly plowed field, and wonders if the time will come when she will be able to walk there peacefully rather than be stabbed by the sharp undergrowth. The parable, I think, is clear.

The poem was first printed in early 1943. Was Leah Goldberg already aware of the Holocaust occurring in her native lands? Or was she ‘merely’ referring to the hoary Jewish history of persecutions and pogroms? No matter. The relevance of the poem to our post-October 7 pogrom feeling is clear. We have been ravaged, we have been devastated, we survive to yearn for peace.

It seems to me that The characteristic theme of Jewish writing throughout history, including the liturgy, is the irrational but irrepressible aspiration for peace in the face of neverending persecution and destruction. Our history is filled with tragedy. Our hearts are filled with sorrow and hope.

Only one thing has changed in the last 2000 years—we now have a homeland, a vibrant, thriving society with a people’s army to defend ourselves. Yonah’s dove has found its foothold in our homeland, albeit in a terrible neighborhood. Perhaps someday we will be able to walk in our plowed fields “like one of the grasses, like anyone.”

| האמנם האמנם עוד יבואו ימים בסליחה ובחסד ותלכי בשדה ותלכי בו כהלך התם | Indeed? Indeed? Will there come days of forgiveness and grace and you’ll walk in the field and you’ll walk in the field like an innocent? |

| ומחשוף ומחשוף כף רגלך ילטף בעלי האספסת או שלפי שיבולים ידקרוך ותמתק דקירתם | And will the bareness, the bareness of your sole brush the alfalfa leaves or will the stalks of the reeds stab you, with sweet pricks? |

| או מטר ישיגך בעדת טיפותיו הדופקת על כתפייך חזך צווארך וראשך רענן ותלכי בשדה הרטוב וירחב בך השקט כאור בשולי הענן | Or will the rain catch you in the pounding swarm of its drops on your shoulders, your breasts, your neck and your fresh head And you’ll walk in the wet field and the quiet will swell in you like the light at the edge of a cloud? |

| ונשמת ונשמת את ריחו של התלם נשום ורגוע וראית את השמש בראי השלולית הזהוב | And you breathe, and you breathe in the smell of the furrow Breathed and at ease and you see the sun in the mirror of a golden puddle? |

| ופשוטים ופשוטים הדברים וחיים ומותר בם לנגוע ומותר לאהוב ומותר ומותר לאהוב | And they’re plain, and they’re plain things and life and them you may touch and you may love and you may, and you may indeed love. |

| את תלכי בשדה לבדך לא נצרבת בלהט השרפות בדרכים שסמרו מאימה ומדם וביושר לבב שוב תהיי ענווה ונכנעת כאחד הדשאים כאחד האדם | You shall walk in the field by yourself Not singed by the heat of the fires along the way that panged from terror and from blood but with an upright heart again you shall be modest and accepting like one of the grasses, like anyone. |

I loved hearing the various performances of the song. The song is indeed a classic.

Chava is great, as are her songs.

Whatever she sings about, she sings with emotion.

Very moving. Thanks Jeff.

I love her passion. In it I hear the resolve of the Jewish people. Thank you for posting these songs.