Last week, in SoTW 126, we presented Bob Dylan’s original performance of ‘Tears of Rage’ from “The Basement Tapes”. This week we’re presenting ‘Tears of Rage’ as it appears on The Band’s first album, “Music from Big Pink”.

In July, 1968, hippies were being beaten in Chicago, Black ghettos were on fire, RFK and MLK had been killed, Paris was under siege and Prague was invaded. “Battle lines being drawn.” Rock music was the vehicle for the younger generation to rail against parents, professors, police – louder and faster and flashier, more and more strident and abrasive and combative. Get high, get angy, get laid. Up against the wall, motherfucker.

Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding” had provoked nothing more than a collective “Huh?” “Sgt Pepper” had deteriorated into Deep Purple and Iron Butterfly and Vanilla Fudge and Steppenwolf and The Doors and Cream .

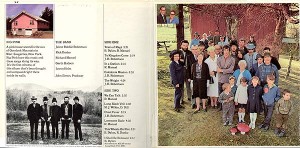

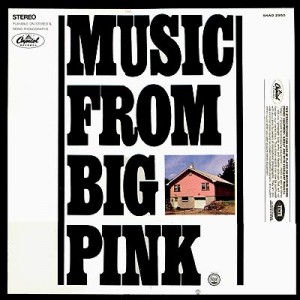

Then Bob Dylan’s backing band – formerly The Hawks, now the non-name The Band – released their first album. The back cover pictured a pink house (hence the title “Music from Big Pink”), and inside was a photo of five guys who looked more like the James Brothers – the gang, not the band. Even worse, they included a picture of a whole tribe of horn-rimmed honkies, captioned ‘Next of Kin’. This was in a day when everyone else was denying that they had biological parents. Didn’t these guys know anything about being cool?

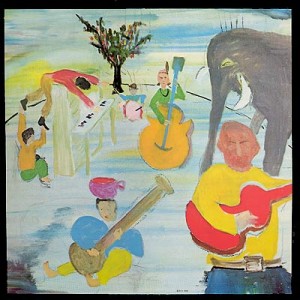

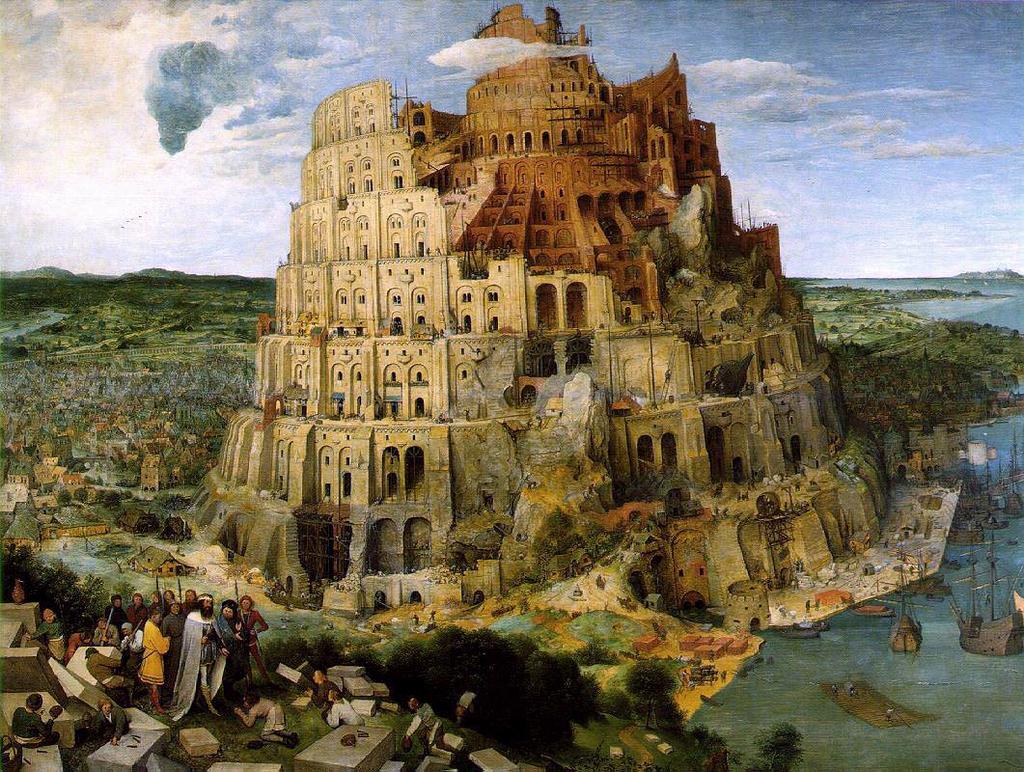

But the front cover was a primitive painting of the group by The Dylan himself. Not only that, the album featured three songs by him, two of them collaborations with The Band (music for ‘Tears of Rage’ by Richard Manuel, for ‘This Wheel’s on Fire’ by Rick Danko, together with ‘I Shall Be Released’). This was at a time when Dylan no more collaborated with mortals than did The Almighty Him/Herself. So “Music from Big Pink” entered the marketplace as an authoritative word from on high, if not Dylan himself speaking, then at least his angels.

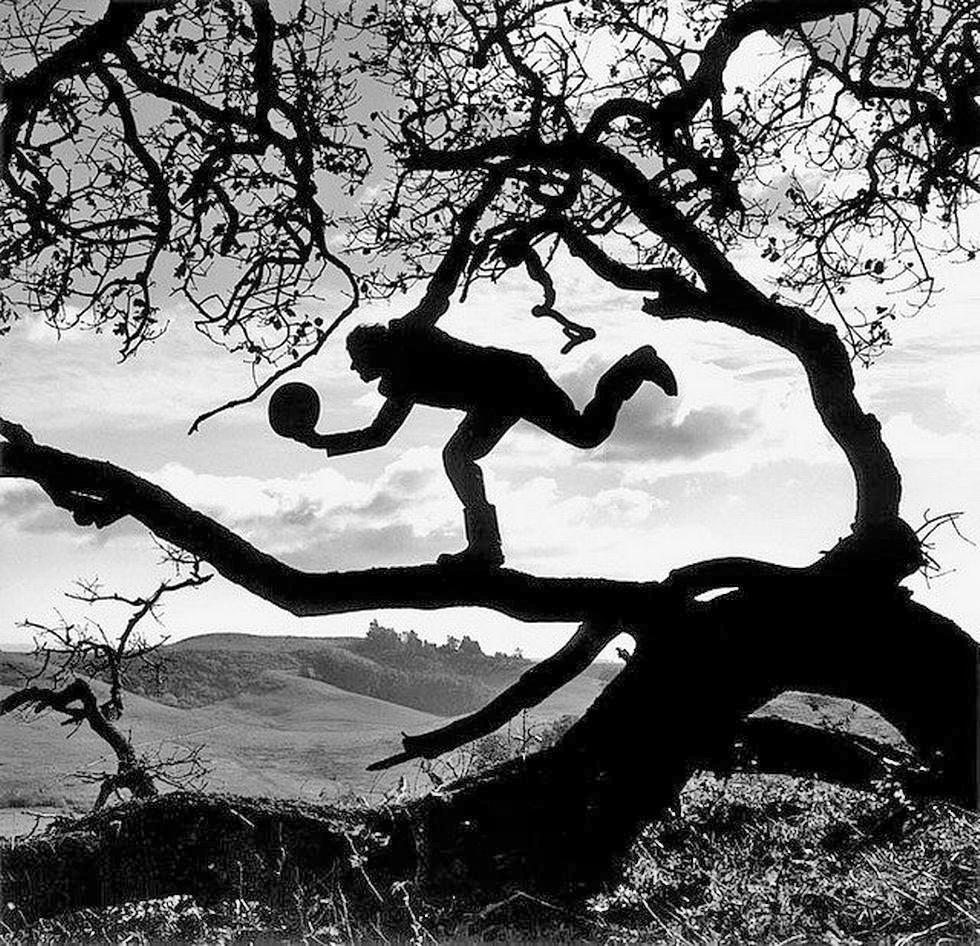

But the music? It was so strange. Nary a backbeat on the entire LP. Nothing you could dance to. No electricity. It all sounded as though it had grown up through the ground. The instruments sounded as though they had been picked off a stalk and hand-fashioned. The songs talked about family, faith, and rural life. Talk about ‘Huh?’!

But the music? It was so strange. Nary a backbeat on the entire LP. Nothing you could dance to. No electricity. It all sounded as though it had grown up through the ground. The instruments sounded as though they had been picked off a stalk and hand-fashioned. The songs talked about family, faith, and rural life. Talk about ‘Huh?’!

Its impact was subtle but immediate. Eric Clapton heard the album and decided on the spot to break up Cream. It would take us all years to absorb the music from Big Pink – the polar opposite of everything we were experiencing at the time: ensemble music, acoustic, organic. Roots music in a wholly new style. Five individuals performing as a single unit in a way common to jazz and chamber music, unknown in rock. Listening rather than shouting.

The music created a new aural palette—a rhythm piano (Richard Manuel); a “fourth-dimensional” organ providing distinctive colorings and lead voices (Garth Hudson); a guitar (Robbie Robertson) pursuing a holistic sound; and a drum (Levon Helm) taking an equal creative role in the musical pastiche. Their vocals were a wonder – Levon usually taking the lead (‘The Weight’), the authentic drawling Southerner aside four Canadians; reedy Danko (‘This Wheel’s On Fire’), simultaneously vulnerable and raucous; and the miracle of Richard Manuel’s voice (‘Tears of Rage’, ‘I Shall Be Released’ in a harrowing falsetto, gut-wrenching ‘Lonesome Suzie’ – passionate, expressive, joyous, pained, his eventual suicide already foreshadowed). Producer John Simon also played a critical role in pulling it all together, playing horns with Garth, tweaking the marvelous sounds that are as much a feature of the album as the songs and the musicianship.

It is remarkable to think that this quantum shift didn’t have to occur; it was a product of Bob Dylan’s decision to pull off the fast lane.

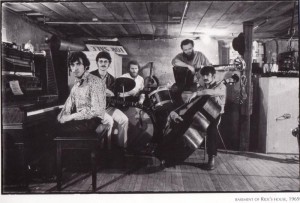

The Hawks had been touring Canada and the South as a heavy, funky rock/rock&roll/country-tinged rhythm&blues band for five years when they were drafted to back Dylan as the band he used to electrify his sound. They were booed nightly. (I saw one of these performances—it was so raw and raunchy the rafters literally shook; Robbie’s guitar was deafening. I refrained from joining the booing only out of respect for Dylan.) Dylan crashed on his motorcycle, and the whole group retired to the Saugerties near Woodstock, where they took their first break from the road in years. They hung out, walked in the woods, and met daily in the basement to play the old music they loved and recreate the sound and mindset of America.

Robbie Robertson: “My guitar playing was like a premature ejaculation in the beginning. I was in my early twenties with Bob Dylan. Same thing, a hundred guitar solos a night. I’d done this to death…I wanted to discover the sound of the band. ..I’m not gonna play a guitar solo on the whole record. I’m only going to play riffs, Curtis Mayfield kind of riffs. I wanted the drums to have their own character. I wanted the piano not to sound like a big Yamaha grand. I wanted it to sound like an upright piano. I wanted these pictures in your mind. I wanted this flavor. I didn’t want screaming vocals. I wanted sensitive vocals where you can hear the breathing and the voices coming in. This whole thing of discovering the voices…This is emotional and this is story telling. You can see this mythology. This is the record that I wanted to make. “

Drummer Levon Helm, from his autobiography “This Wheel’s on Fire”: “’Tears of Rage’” opened the album with a slow song, which was just another way of our rebelling against the rebellion. We were deliberately going against the grain. Few artists had ever opened an album with a slow song, so we had to. At the zenith of the psychedelic music era, with its flaming guitars and endless solos and elongated jams, we weren’t about to make that kind of album. Bob Dylan helped Richard with this number about a parent’s heartbreak, and Richard sang one of the best performances of his life. It had those trademark horns and organ and the moaning tom-tom style of drumming that I’ve been credited with by some observers, but I know that Ringo Starr was doing something like it at the same time. [JM: Cf the deadened tom-tom sound Ringo invented on ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’.] You make the drum notes bend down in pitch. You hit it, it sounds, and then it hums as the note dies out. If the ensemble is right, you can hear the sustain like a bell, and it’s very emotional. It can keep a slow song suspended in an interesting way. (John Simon heard this and started calling me a bayou folk drummer, but not to my face.)”

What is most remarkable to me today about “Music from Big Pink” in general and ‘Tears of Rage’ specifically is the way they assemble the music through mutually interdependent lines. Just like jazz at its best. Listen to the original version of ‘Tears of Rage’ from “The Basement Tapes.” Even wooden-fingered Jeff can play that guitar part, strum-two-three-four, strum-two three-four. Now listen to the opening of The Band’s ‘Tears of Rage’, the very opening of this miraculous album. What’s going on? Where is the rhythmic center? We don’t hit an identifiable marker until about the eighth bar—it’s just intertwining and floating, but all in tandem, a pas de cinq ballet of sounds. So much of what the Band invents can be found right here in this instrumental introduction—the ‘Curtis Mayfield’ guitar riff, the lead voice, but so much an integral part of the whole; the almost inaudible but crucial floating sustained organ; the interplay of the bass and the drum and the rhythm piano, together providing an implicit rhythm created as much by the gaps as by the beats, as intimate as lovers, as self-effacing as monks, as synchronized as guys who have been travelling together for six years.

What is most remarkable to me today about “Music from Big Pink” in general and ‘Tears of Rage’ specifically is the way they assemble the music through mutually interdependent lines. Just like jazz at its best. Listen to the original version of ‘Tears of Rage’ from “The Basement Tapes.” Even wooden-fingered Jeff can play that guitar part, strum-two-three-four, strum-two three-four. Now listen to the opening of The Band’s ‘Tears of Rage’, the very opening of this miraculous album. What’s going on? Where is the rhythmic center? We don’t hit an identifiable marker until about the eighth bar—it’s just intertwining and floating, but all in tandem, a pas de cinq ballet of sounds. So much of what the Band invents can be found right here in this instrumental introduction—the ‘Curtis Mayfield’ guitar riff, the lead voice, but so much an integral part of the whole; the almost inaudible but crucial floating sustained organ; the interplay of the bass and the drum and the rhythm piano, together providing an implicit rhythm created as much by the gaps as by the beats, as intimate as lovers, as self-effacing as monks, as synchronized as guys who have been travelling together for six years.

“Music from Big Pink” is too weighty a work to try to deal with it in its entirety. I’m struggling to give just the first cut a fair shake. I guess I’ll just have to (get to!) revisit some of the other wondrous songs another time. Last week I tried to give an honest reading of the song as its author performed it. But that, for all the beauty and wisdom of the song, is clearly a sketch of a rendition, still in its adolescence. Here, in The Band’s treatment, it finds its full, organic expression. Manual’s voice together with Garth’s organ and the tambourine and – oh, there’s just no end to the richness of this tapestry. It can’t be plumbed, it can’t be dissected or measured. Just sit back and let it rend your heart.

For further edification:

The wonderful Norwegian Web site chronicling all things Band.

Al Kooper’s 1968 review in Rolling Stone magazine of the Album of the Year, “Music from Big Pink”

Alternate version of ‘Tears of Rage’ from the “Big Pink” sessions

An unsuccessful ‘Tears of Rage’ by Manuel and Danko from the LP “Whispering Pines” (1985)

A very successful ‘I Shall Be Released’ by Manuel and Danko from the LP “Whispering Pines” (1985)

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy:

126: Bob Dylan, ‘Tears of Rage’ (The Basement Tapes)

A bizarre personal story of mine regarding the house, Big Pink

087: Bob Dylan, ‘Black Diamond Bay’

016: Bob Dylan, ‘Percy’s Song’

008: ‘I’ll Keep It With Mine’, Fairport Convention (Bob Dylan)

You’ve captured the awe many of us felt when this album appeared. 43 years later we know much of the the music is timeless. Thanks for explaining in words what we feel in our hearts.

These keep getting better and better. When is your book coming out?

i was choking on laughter by the third paragraph! and your analysis was righteous too – i knew i liked all the inter-generational mingling the album referenced but until your article i hadn’t thought of the perfection of the opening cut in that context. thanks/keep it up.

Dylan’s version from last week is much better. No comparison.

You Keep Me Hanging On by Vanilla Fudge is one of my favourite songs of all time. However, I had never heard anything else by them until YouTube came around and now it seems that their Motown cover is the only thing I like of theirs.

I went to see The Band once at Varsity Stadium. I think it was on Labour Day. It was chilly outside and they were so late – hours – that I left without seeing them.

After seeing The Rolling Thunder Revue at Maple Leaf Gardens we went down the street to see Ronnie Hawkins at The Nickelodeon (his bar) because we thought that Dylan might show up. He did. But Ronnie Hawkins had a great band backing him with a great singer alongside him and it was a much better show than The Revue.

I’m eternally grateful for the confluence of events and talent that gave birth to The Band. Your lovely SOTW perfectly nails the musical zeitgeist of the time and the impact such a singular, against-the-grain, and welcome new aggregation had on many of us longing for a return to simplicity, sincerity, soul and feeling in music. Thanks for another gem, Jeff.