‘De profundis’ –Arvo Pärt (Paul Hillier, Theater of Voices)

‘Cantate Domino’–Arvo Pärt (Paul Hillier, Theater of Voices)

II don’t consider myself to be a very spiritual person. I’m empirical, skeptical and cynical, dwelling in the here and now. If pressed, I define myself as ‘observant’, rather than ‘religious’. But Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is upon us, and some sort self-reckoning is enescapable.

Last week we snuck outside the synagogue for a spiritual boost from Brother Ray and Sister Aretha’s Southern Baptist fervor. This week, as the gates creak slowly closed, we’re traveling all the way to the Baltic Sea for musical inspiration from a contemporary classical composition of Psalm 130, a central prayer in these Days of Repentence:

שִׁיר הַמַּעֲלוֹת: מִמַּעֲמַקִּים קְרָאתִיךָ ה’.

1 Out of the depths have I cried unto Thee, O Lord.

אֲדֹנָי, שִׁמְעָה בְקוֹלִי: תִּהְיֶינָה אָזְנֶיךָ, קַשֻּׁבוֹת – לְקוֹל, תַּחֲנוּנָי.

2 Lord, hear my voice: let Thine ears be attentive to the voice of my supplications.

אִם-עֲוֹנוֹת תִּשְׁמָר-יָהּ – אֲדֹנָי, מִי יַעֲמֹד.

3 If Thou, Lord, shouldest mark iniquities, O Lord, who shall stand?

כִּי-עִמְּךָ הַסְּלִיחָה – לְמַעַן, תִּוָּרֵא.

4 But there is forgiveness with Thee, that Thou mayest be feared.

קִוִּיתִי יְהוָה, קִוְּתָה נַפְשִׁי; וְלִדְבָרוֹ הוֹחָלְתִּי.

5 I wait for the Lord, my soul doth wait, and in His word do I hope.

נַפְשִׁי לַאדֹנָי– מִשֹּׁמְרִים לַבֹּקֶר, שֹׁמְרִים לַבֹּקֶר.

6 My soul waiteth for the Lord more than they that watch for the morning: I say, more than they that watch for the morning.

יַחֵל יִשְׂרָאֵל, אֶל-ה’: כִּי-עִם-ה’ הַחֶסֶד; וְהַרְבֵּה עִמּוֹ פְדוּת.

7 Let Israel hope in the Lord: for with the Lord there is mercy, and with him is plenteous redemption.

וְהוּא, יִפְדֶּה אֶת-יִשְׂרָאֵל – מִכֹּל, עֲוֹנֹתָיו.

8 And He shall redeem Israel from all his iniquities.

Those are some powerful words there, in any language, for me especially in Hebrew, the language I pray in. Correction, that I read the words in. If I can carry some of this music’s gravity into synagogue with me, maybe I can achieve ‘prayer’.

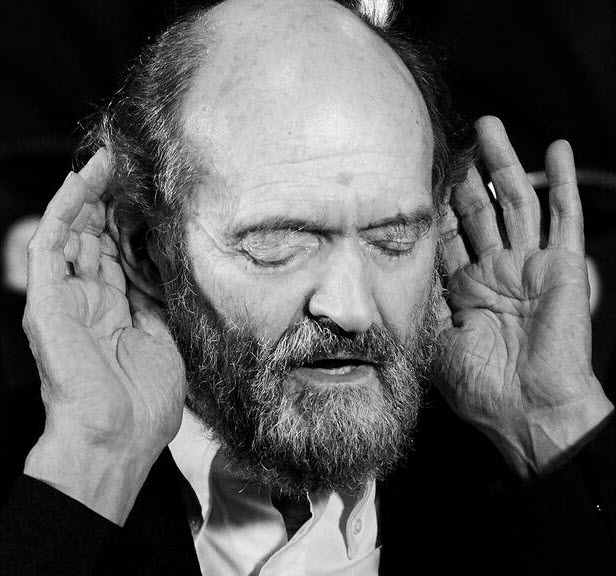

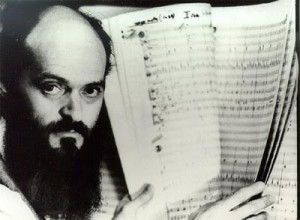

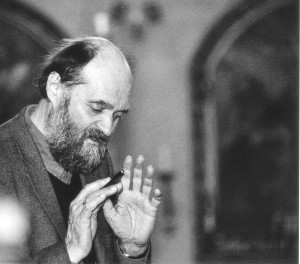

Arvo Pärt was born in Estonia in 1935, composed furiously in the tonally severe vein of Bartok, then in the serialist mode of Schoenberg, which got him into a heap of trouble with the Soviets, then he stopped composing completely for about a decade, working as a radio engineer. And then he was reborn musically in the early 1970s, heavily influenced by Gregorian and Medieval and Renaissance liturgical music, and apparently motivated by his own devout Russian Orthodox belief.

He emigrated from Estonia in 1980, ultimately settling in Berlin, where he still lives and composes. The piece attached here is ‘De Profundis’ (Psalm 130), composed in 1977 (Pärt’s composition, not the psalm, which was composed about 2500 years ago), performed by Paul Hillier’s Theatre of Voices, four men, an organ and percussion.

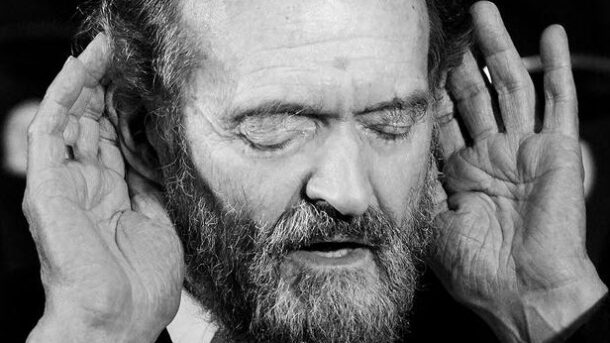

Pärt’s music is elevated, glorious, full of gravitas, gorgeous. I’ve known this CD for a number of years, but it recently started speaking to me in a certain quiet voice that’s riveted my attention, and I’m working hard at broadening my appreciation for his work. Actually, I’ve listened to nothing else. That’s deep immersion, even for me. But those gates are creaking closed, and thinking about what lies ahead in the coming year gives pause for reflection.

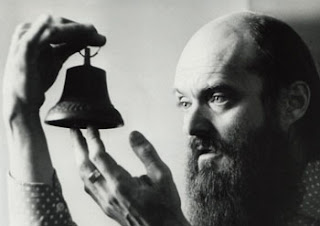

He frequently employs a technique he calls ‘tintinnabuli’, a bell-like sustained triad. His music doesn’t really move forward in the standard Western dramatic sense of tension and release, complications and resolutions. It’s as thought he’s not interested in getting anywhere, just in letting go and floating up into a rarer place. Kind of like what we’re supposed to be doing in our Yom Kippur prayer. It’s as if the music exists outside time, outside the turmoil of tempo, in peace and harmony. Utter simplicity, utter serenity. Much of his music is choral. He calls the voice “the most perfect instrument of all”.

“Tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers – in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have the certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning. The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises – and everything that is unimportant falls away. Tintinnabulation is like this. . . . The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I call it tintinnabulation.”

Well, thank heaven he usually writes music, not words, and thank heaven mostly I listen to him rather than talk about him.

Some people associate him with the ‘minimalists‘, but I hear quite a lot happening. I sure wouldn’t call him any names at all. So let’s check our cynicism at the gate, settle in and relax. Make sure there’s no one about to disturb, and crank the speakers way up loud. Let the music float, and float with them, those tintinnabulous triads.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

073: Erik Satie, ‘Gymnopédie No. 1′

084: Dmitri Shostakovich, Prelude & Fugue No 16 in B-flat Minor (Tatiana Nikolaeva)

Since, as you pointed out, it really dosen’t go anywhere – I find it very annoying. Sort of like a quiet version of trance music, repitition, repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition,repitition.

See – annoying!

You not only write with an open mind, but with an open heart as well. Lovely music and a sincere review.

I loved it. I do feel like I’m in a trance after listening to it. I didn’t find the repetition boring or annoying at all, just lovely and mesmerizing.

from R.Z.:

Thanks Jeff.

Beautiful. Heaven, (I hope), it is…

I love it. Great!

Can be bought in stores… Acquired… Yeah sure. 🙂 Very beautiful, the kind of music my wife would like at first but then ask for more Shlomo Artzi. Doesn;t go anywhere, no grand finale, but I wouldn’t bother listening to it more than a few minutes at a time.

Have you checked moondog ? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moondog Also one of the exponents of minimalist music, it was said that he couldn’t compose very well so everyhting was written in major chords. I like him as well.

And if you tell me that you can buy his stuff at stores (you can’t) I will laugh.