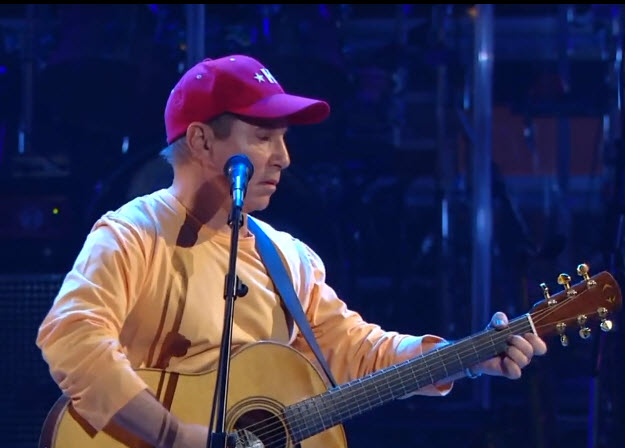

Bob Dylan – ‘All Along the Watchtower’

I set aside several days last week to catch up on reading my fan mail, when I came across this one:

I set aside several days last week to catch up on reading my fan mail, when I came across this one:

Dear Jeff, I’ve been following your blog faithfully for years and enjoy it most of the time (especially that one about Blind Willie Greenberg’s “I Ate Your Cat, Now You Bite My Dog”), although you certainly should be talking more about Texas swing. You wrote last week that you consider “John Wesley Harding” one of your “Top 10” albums (that is a pretty cheesy concept, don’t you think, Jeff?), but that you “almost never” listen to it. Well, Jeff, I hardly know what to say. How would you feel if I wrote a lyric “Oh, that SoTW blog is fine/But to read it I never seem to have the inclination nor the time”??

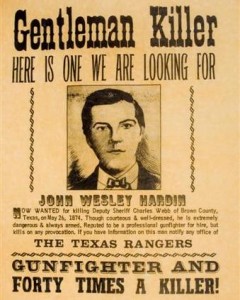

Can you imagine my unmitigated mortification? My utter chagrin? So we begin our third centenary of posts with a rectification: Rehabilitating John Wesley Harding.

For the innocents, ignorants and yung ‘uns amongst you—that’s a joke. I was employing irony, because Bob Dylan so patently needs nothing from me (or anyone), especially not JWH. It’s perhaps the most ‘serious’ album to come out of the entire rock oeuvre – ‘serious’ in the sense of intellectually profound, affectively incisive and craftsmanly masterful. Bob Dylan at his best. Which is to say the art of our time at its best. For time capsules, for satellites to distant universes, for future generations: this is what we had to offer.

From January 1964 to May 1966, Dylan released five generation-defining albums. Not defining in the sense of ‘explaining the nature of’, but in the sense of ‘determining the boundaries of’. We would wait at the record store on the day of the release of a new album of Dylan (and The Beatles). Standing in line we’d ponder, “I wonder where he’s taking us now? What will be our landscape be for the next year?” Little did we know that we’d still be pondering those same questions 50 years later.

In July, 1966, two months after the release of the seminal “Blonde on Blonde”, Dylan broke his neck in a motorcycle accident. Rumors were rife: he’s a paraplegic; he’s permanently out of commission. We knew nothing. In December, 1967, “John Wesley Harding” was released, to our utter bewilderment.

“BoB” had been a living nightmare – electric, haunted, amphetamine-fevered: Lights flicker from the opposite loft/In this room the heat pipes just cough/The country music station plays soft/But there’s nothing, really nothing to turn off/Just Louise and her lover so entwined/And these visions of Johanna that conquer my mind/…The ghost of electricity howls in the bones of her face/Where these visions of Johanna have now taken my place.

And then comes “John Wesley Harding”, mostly minimalist 3-verse songs, acoustic guitar/gentle bass/brushed drums, rife with biblical imagery and judiciously crafted clichés, a landscape of wide-open spaces and allusions to the antiquated, the world of a man still dazed from a personal tsunami, gingerly embracing the time-tried. If it’s been here for a long time, it has some dimensionless gravitas. Dylan presents us with the dialectics of The Desperado and The Destitute. The Landlord and the Homeless. The Immigrant and The Enfranchised. The Deceiver and The Deceived. Frankie Lee and Judas Priest. The Joker and The Thief. And the mortal, moral ground between them.

This is Bob Dylan the survivor, seriously addressing serious issues, taking stock après le deluge. Remember what Noah did after being cooped up with everything from aardvarks to zebras? He sets foot on dry (well, muddy) land, and what does he see? Nothing. The aftermath of absolute holocaust. A cleansing. An existential reboot. So what does Noah do? What would anyone do? He thanks God.

In the words of a song from “The Basement Tapes”, which Dylan was recording at the same time as “JWH”: “Strap yourself to a tree with roots, you ain’t going nowhere.”

From the cover to the liner notes (do yourself a favor, revisit them; they’re Dylan at his very finest) through the 12 songs, Dylan reveals a unified, variegated vision. Each with its own corner of the universe, together adding up to a coherent, disturbing attempt at resolution of the disparate and irreconcilable.

The most disturbing, the most patently visionary song of the 12 is ‘All Along the Watchtower’. The lyric can be distilled thus:

Joker: The world is intolerably harsh.

Thief: Live with it.

Narrator: Ominous things lie ahead.

Not very comforting, I admit. There are prophets of doom, and there are prophets of comfort. But Dylan is no prophet at all (Time and Newsweek notwithstanding). A prophet is claimed (by himself or others) to have been contacted by God and to serve as an intermediary with humanity. Dylan is a mere medium, all veils and masks and giving you a glimpse of what should have been and what yet might be. But has no obligation to tell Dylanists anything.

Bob Dylan has no God. At least not in December, 1967. A dozen years later he would have a whole series of them. But at this point, the whole vision is on him, take it or leave it. We all took it. And the world changed direction. From rocketing forward faster and louder and higher to – wait a minute. Ssh. Ssh. Just breathe. Relax a moment. And think about what’s going on. Live with it.

So what’s going on in this song? We have an intercourse between two 2-dimensional, Kafkaesque figures. (Let that roll around your mind a bit, just how much Bob sounds here like Franz sans guitar.) The third verse is eschatological (relating to The End), a portent of doom. But is it really apocalyptic (i.e., alluding to the secrets revealed to the prophet about the structure of the heavens, the future, the end of days, angels)? Does the narrator know things? I don’t think so.

I think the narrator, and hence the narration, is at most a barometer, a weather vane, a harbinger. Not a bearer of answers. And as he’s long known—you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows. Now he’s providing a service, a wake-up call. But it’s us who need to get ourselves up and moving.

The imagery could hardly be more profoundly frightening, Dylan at his finest. Even if he snitches a bit from Isaiah 21:6–9:

כי כה אמר אלי ה’ לך העמד המצפה אשר יראה יגיד

For thus the Lord said to me: ‘Go, set a watchman; what he sees, let him declare.’

וראה רכב צמד פרשים רכב חמור רכב גמל והקשיב קשב רב-קשב

And when he sees a troop, horsemen by pairs, a troop of asses, a troop of camels, let him heed it most attentively.

ויקרא אריה על-מצפה ה’ אנכי עמד תמיד יומם ועל-משמרתי אנכי נצב כל-הלילות

And he shall cry like a lion: ‘Upon the watchtower, O Lord, I always stand all day on my watch, I am at my post all night.’

והנה-זה בא רכב איש צמד פרשים ויען ויאמר נפלה נפלה בבל וכל-פסילי אלהיה שבר לארץ

And, behold, here it comes, a troop of men, horsemen by pairs.

And he spoke and said: ‘Fallen, fallen is Babylon; and all the graven images of her gods are broken unto the ground.’

‘Fallen, fallen is Babylon.’ Well, that’s conclusive. And comforting! But we’re living 2500 years later, and the answers – some of them, anyway – that worked then no longer hold. The world is complex, the slope is slippery, and even time isn’t what it used to be. Sorry, Joker, there is no way out of here. Yeah, it sucks. Live with it. The hour is getting late.

Look, for example, at God. He had a similar dilemma. Noah stepped off the ark, saw that only he and his family and passengers remained After the Flood, and made a burnt offering. “And God smelled the savory smell; and God said in His heart, “No more will I curse the ground for Man, because the impulse of Man’s heart is evil from youth, and I will no more punish all living things as I just did.”

I made Man, and I made the world for him. He has an evil impulse, and I’m not pleased with that. But I guess I’ll just have to reconcile myself to the world as it turned out.

And what about those two riders? What tidings are they bearing? It don’t sound good!

Well, don’t ask me. I have no idea. But they are fast approaching, so maybe we’ll have an answer soon. Tune in next week.

All Along the Watchtower

“There must be some way out of here,” said the joker to the thief,

“There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief.

Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth,

None of them along the line know what any of it is worth.”

“No reason to get excited,” the thief, he kindly spoke,

“There are many here among us who feel that life is but a joke.

But you and I, we’ve been through that, and this is not our fate,

So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late.”

All along the watchtower, princes kept the view

While all the women came and went, barefoot servants, too.

Outside in the distance a wildcat did growl,

Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl.

A factual correction: Drummer Kenney Buttrey is using sticks, not brushes, on “All Along The Watchtower.”

enjoyed a lot!

Thanks for the writing and passion. And what a great song indeef. I think the song deserves a mention of Jimi Hendrix’s inspired version. Lastly, sorry to be pedantic but Noah was in the ark for a little over a year.

Great song, done better IMHO by Hendrix, in part (again, IMHO) because there was no annoying harmonica braying. Dylan was a lot of things, but a virtuoso on the harmonica wasn’t apparently one of them.

I’ve heard this song 254 times but I never thought about it like this. Thank you.