Thelonious Monk, ‘Let’s Call This’

Once upon a time, the word ‘cool’ meant “of moderately low temperature”. This week ‘cool’ has been reduced to meaning ‘good’, as in “I’ll meet you at the peanut butter factory at 5.” “Cool.” But in between, especially in the 1950s, it referred to a restrained demeanor, especially pertaining to black males.

In his fine book “Birth of the Cool”, poet Lewis MacAdams quotes emotionologist Peter Stearns saying that cool symbolizes “our culture’s increased striving for restraint” to better blend into the social fabric, an attitude that “has become an emotional mantle, sheltering the whole personality from embarrassing excess.” Emotionologist, huh? Maybe that’s what I’ll be when I grow up.

‘Cool’ expressed itself in all sorts of unexpected arts in the 1950s–-poetry, stand-up comedy, Broadway-–but none more prominently than in jazz. ‘Cool jazz’ was actually born from the meeting of Miles Davis and Gil Evans. Miles (b. 1926) was the product of a bourgeois black family, a refined European musical sensibility, and the hot, drug-laden band of the father of modern jazz, Charlie Parker. Gil Evans (b. 1912) was his hip, white mentor, deeply grounded in avant garde theory. Together they made the landmark “Birth of the Cool” recordings in 1948, which we talked about way back in SoTW 35.

‘Cool’ expressed itself in all sorts of unexpected arts in the 1950s–-poetry, stand-up comedy, Broadway-–but none more prominently than in jazz. ‘Cool jazz’ was actually born from the meeting of Miles Davis and Gil Evans. Miles (b. 1926) was the product of a bourgeois black family, a refined European musical sensibility, and the hot, drug-laden band of the father of modern jazz, Charlie Parker. Gil Evans (b. 1912) was his hip, white mentor, deeply grounded in avant garde theory. Together they made the landmark “Birth of the Cool” recordings in 1948, which we talked about way back in SoTW 35.

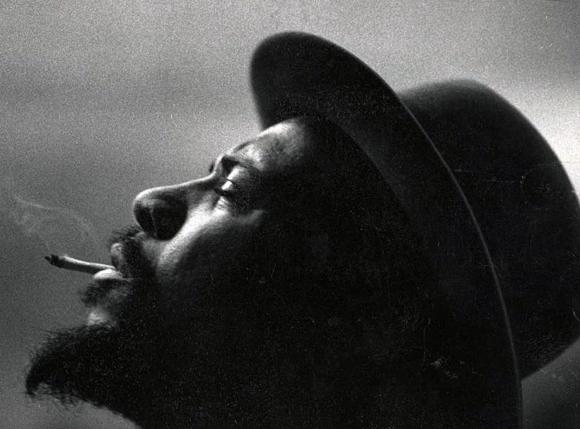

But of course it wasn’t so simple. Cool was in the air before, and one of the most remarkable creative artists to inform that spirit was the singular pianist Thelonious Monk (1917-1982). ‘Individualist’ doesn’t even begin to describe Monk. He had pretty much formed his own style in the early 1940s. At the beginning it was only ‘quirky’, but it quickly evolved into ‘weird’. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie tried to bring him into the bebop orbit, but Monk didn’t adhere to the pull of anyone else’s gravity. He played very few notes, and those unpredictable. Metronomes were witnessed imploding in his presence. He pounded the keyboard with extended, flat fingers. He got up in the middle of a song to dance. He wore funny hats. Sometimes he just refused to talk.

But of course it wasn’t so simple. Cool was in the air before, and one of the most remarkable creative artists to inform that spirit was the singular pianist Thelonious Monk (1917-1982). ‘Individualist’ doesn’t even begin to describe Monk. He had pretty much formed his own style in the early 1940s. At the beginning it was only ‘quirky’, but it quickly evolved into ‘weird’. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie tried to bring him into the bebop orbit, but Monk didn’t adhere to the pull of anyone else’s gravity. He played very few notes, and those unpredictable. Metronomes were witnessed imploding in his presence. He pounded the keyboard with extended, flat fingers. He got up in the middle of a song to dance. He wore funny hats. Sometimes he just refused to talk.

You talk about a different drummer? This cat inhabited a not-so-parallel universe.

Monk had lots of ups and downs in his career, including years spent in seclusion, forgotten and ignored, as well as periods of incredible productivity. Along the way he left a library of distinctive, inimitable music. He inspired no schools, because no one could figure out his footsteps. But musicians continue to play his hilarious, wacky, totally human music.

He composed and performed some of the best-known standards in the modern jazz songbook: bop classics ‘Straight, No Chaser’ and ‘Blue Monk’ (here from the film “Jazz on a Summer’s Day”), the riveting, elusive ‘Around Midnight’, the heartrending ‘Ruby, My Dear’ (here with Coltrane), and a whole giant oeuvre of fun, funny-whee and funny-huh? gems, such as our SoTW, ‘Let’s Call This’.

First of all, you gotta love the guy’s song titles: Crepuscle with Nellie, Epistrophy, Humph, Pannonica, Trinkle Tinkle.

Secondly, and foremostly, you gotta love the music. It swings, it grins. It completely lacks coherent melody, and you walk around all day humming it. It makes no sense to such an extent that it makes the most perfect of sense.

Thirdly, you gotta dig his aesthetic. We’ll get back to that in a moment.

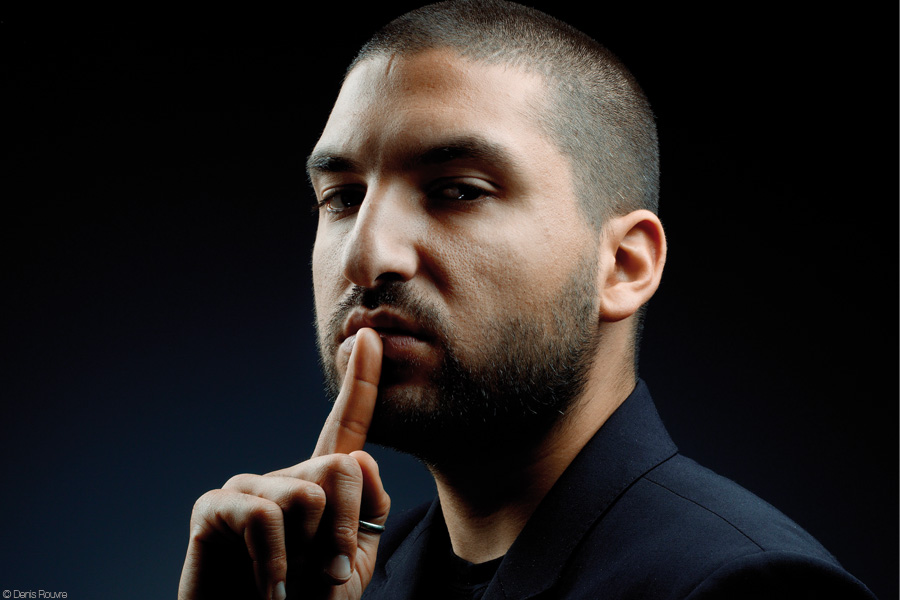

Steve Lacy (b. Steven Norman Lackritz, 1934-2004) was obscure enough for nary a non-jazz aficionado to have heard of him, but a fine enough musician to have won a MacArthur genius grant. He was The Man of the soprano saxophone and a committed Monk devotee. He recorded the first album of all-Monk compositions, “Reflections”, in 1958. Then in 1960 he played in Monk’s band for four months. He continued to explore Monk’s music for the next forty years, often in quartet and duo settings with the dynamite pianist Mal Waldron, a collaboration I discussed even wayer back in SoTW 21.

Let’s take a look at the joyous Monk song ‘Well, You Needn’t’ in his own hands (from “Live at the Blackhawk”, San Francisco, 1960).

And then Lacy’s straightforward 1958 treatment from “Reflections” (with a tame Waldron on piano):

And then the song wrenched and wrangled and strangled and dissected and whopped and whoopeed by Lacy and Mal Waldron from that 4-CD I love so much “Live at Dreher, Paris 1981″:

That just shows you what Monk can do to people when they listen to him too much.

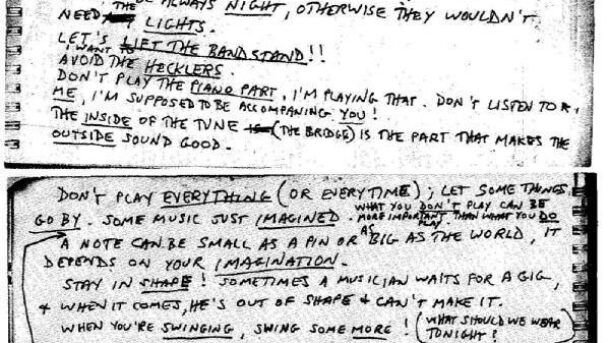

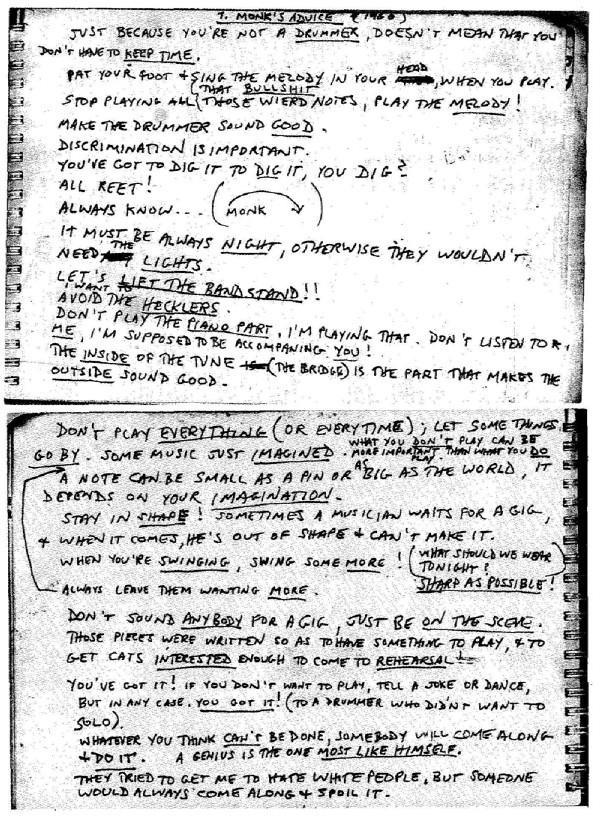

Meanwhile, back at the Thelonious. There’s this remarkable document we’d like to share with you. It is purportedly in Monk’s hand, addressed to Lacy, but that is disputed. Perhaps Monk dictated it to Lacy. It may even have been Lacy’s recollection of the Monktalk. Who knows? In any case, the document speaks for itself. You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig? It’s the essence of cool. It’s the most serious of spoofs and/or the most spoofish of sérieux. Feel free to write in and tell us which one is your favorite. I’ll tell you right now which one is my favorite: all of them.

“A genius is the one most like himself,” Monk says. Clearly, Monk was exactly like Monk.

Just because you’re not a drummer, doesn’t mean you don’t have to keep time.

Pat your foot and sing the melody in your head, when you play.

Stop playing all those weird notes (that bullshit), play the melody!

Make the drummer sound good.

Discrimination is important.

You’ve got to dig it to dig it, you dig?

ALL REET!

Always know….(MONK)

It must be always night, otherwise they wouldn’t need the lights.

Let’s lift the band stand!!

I want to avoid the hecklers.

Don’t play the piano part, I’m playing that. Don’t listen to me. I’m supposed to be accompanying you!

The inside of the tune (the bridge) is the part that makes the outside sound good.

Don’t play everything (or every time); let some things go by. Some music just imagined. What you don’t play can be more important that what you do.

A note can be small as a pin or as big as the world, it depends on your imagination.

Stay in shape! Sometimes a musician waits for a gig, and when it comes, he’s out of shape and can’t make it.

When you’re swinging, swing some more.

(What should we wear tonight? Sharp as possible!)

Always leave them wanting more.

Don’t sound anybody for a gig, just be on the scene. These pieces were written so as to have something to play and get cats interested enough to come to rehearsal.

You’ve got it! If you don’t want to play, tell a joke or dance, but in any case, you got it! (To a drummer who didn’t want to solo)

Whatever you think can’t be done, somebody will come along and do it. A genius is the one most like himself.

They tried to get me to hate white people, but someone would always come along and spoil it.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

010: Charles Mingus, ‘Remember Rockefeller at Attica’

Bebop piano split into two main directions Monk and Evans. I would say that Cecil Taylor inherited from Monk and Brad Meldau from Evans. I love them both.

Favorite line from the letter:

Make the drummer sound good.

“Whatever you think can’t be done, somebody will come along and do it. A genius is the one most like himself.”

If he didn’t say it, he should have!! 🙂

My fave….”a note can be as small as a pin or as big as the world,it depends on your imagination.”

He heard music in a different way, so thankful he shared it, and thank you for the post, it suits him to a T.

your prose gets better and better

Bill Holman has a great affinity for Monk’s music and his Orchestra has played and recorded his arrangements extensively.

You don’t have to play everything, let some things be imagined. And also, the music is what happens between the notes. Mozart said that. These guys are definitely on to something. Thank you for highlighting Monk.