Caution: This week’s SoTW contains content which may be unsuitable for minors and some adults.

“Death and the Maiden” — The Alban Berg Quartet

Before Franz Schubert died in 1828 at the age of 31, Pfennigless and a commercial flop, he had composed 600 Lieder (romantic art songs), nine symphonies, and a whole pile of chamber and solo piano music. His greatest hits include the Marche Militaire for a 4-handed pianist; the “Unfinished” Symphony; the “Trout” string quintet; “Ave Maria” (which started out as a translation of Sir Walter Scott’s poem ‘Lady of the Lake’ beginning with an ‘Ave Maria’ greeting–an 1820 ‘Yo Bro’ – but the text of the entire Latin prayer somehow stuck to the melody); and one of my personal favorites, the String Quintet in C Major. But for our Song of The Week (okay, it’s not a song – sue me) we’ve chosen his hands-down #1 smash hit on the Classical Horror Music chart – “Death and the Maiden” (“Der Tod und das Mädchen”).

Schubert first dealt with the subject at the age of 20 in his 1817 lied “Der Tod und das Mädchen”, the text taken from a poem by a minor German poet, Matthias Claudius:

| Das Mädchen:

Vorüber! Ach, vorüber!Geh, wilder Knochenmann!Ich bin noch jung! Geh, lieber, Und rühre mich nicht an. Und rühre mich nicht an. | The Maiden:

Pass me by! Oh, pass me by!Go, fierce man of bones!I am still young! Go, rather, And do not touch me. And do not touch me. |

| Der Tod:

Gib deine Hand, du schön und zart Gebild!Bin Freund, und komme nicht, zu strafen.Sei gutes Muts! ich bin nicht wild, Sollst sanft in meinen Armen schlafen! | Death:

Give me your hand, you beautiful and tender form!I am a friend, and come not to punish.Be of good cheer! I am not fierce, Softly shall you sleep in my arms! |

Seven years later, acutely aware of his impending death and tortured by his failure to achieve recognition as a composer, he used the theme of the lied as the basis for the second movement (Andante con moto) of the String Quartet No. 14 in D minor, also named “Death and the Maiden”.

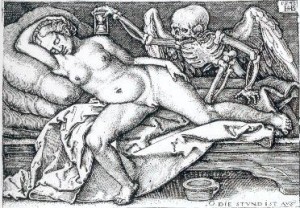

The Death and the Maiden motif first appeared in Medieval art as the “Dance of Death” (Danse Macabre), an allegory on the universality of death: no matter one’s station in life, the Dance of Death unites all. The Danse Macabre consists of personified Death leading representatives from all walks of life (typically a pope, an emperor, a king, a child, and a laborer) to dance along to the grave. These paintings were intended to remind people of the fragility of their lives and how vain were the glories of earthly life.

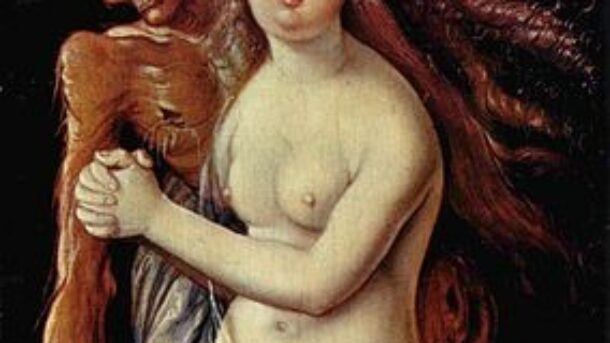

In Renaissance art the motif added an erotic twist and metamorphosed into Death and the Maiden. (The clash between Eros and Thanatos goes all the way back to the Greeks: The young goddess Persephone was gathering flowers in company of carefree nymphs when she saw a pretty narcissus and plucked it. At that moment, the ground opened, Hades came out of the underworld and abducted her. When the Greeks said ‘Don’t pick the flowers!’, Persephie dear, they meant it.)

The Renaissance artists may have been attracted to the virgin as the epitome of vitality, contrasting most sharply with skeletal death. Or, according to scholars more learned than I, they may have used her as an excuse to portray a naked woman. Kind of like slasher movies today, I guess.

In 1517, Hans Baldung Grien painted this painting in which Death seizes a girl by the hair and forces her to go down into the tomb dug at her feet. Death indicates with its right hand the grave. The girl, completely naked, does not try to resist. Her mouth is plaintive, her eyes are red and tears run down on her cheeks; but she understands this is the end.

A couple of years before Schubert wrote his quartet, he wrote to a friend: “Think of a man whose health can never be restored, and who from sheer despair makes matters worse instead of better. Think, I say, of a man whose brightest hopes have come to nothing, to whom love and friendship are but torture, and whose enthusiasm for the beautiful is fast vanishing; and ask yourself if such a man is not truly unhappy.”

Well, he was no innocent – he was dying of advanced syphilis. But he certainly knew something about Death. His “Der Tod und das Mädchen” is a harrowing expression of the spectre of his imminent end; in the words of critic Andrew Clements, “its bleak vision and almost unremitting foreboding”.

It’s some of the most dramatic music I know, hyper-energetic throughout, an astounding amount of music for sixteen strings played by sixteen fingers (well, seventeen if you count the cellist’s thumb). There’s a notable lack of solo voices throughout–more often two pairs playing in tandem.

Schubert’s one accomplishment during his lifetime was to inspire devotion from a close circle of supporters. In life, as the maiden so painfully learns, you go to the grave alone. But harmony, as this quartet shows so memorably, is made with the help of your friends.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

124: Bill Evans, ‘Nardis’ (another dying artist shouting at his approaching death)

077: J.S. Bach, ‘The Art of The Fugue’

012: Arvo Pärt, ‘Cantate Domino’

Best yet. Really learned a lot from this week’s SoTW.

Got to love Schubert.

A lovely piece, quite melodic and soothing – if one didn’t know the topic.

A very interesting sotw – Thanks Jeff!

Jeff, a well written and informative piece. Thanks. While not a big fan of classical, you really brought this music to life. No pun intended

I love the music…

(Death and the Maiden (1994) – http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0109579/ ) – very good movie, but very difficult to watch ….

Jeff, thank you for the background on the music (and all your other posts….)

I saw the play on stage once upon a time. Indeed, a hard one to take.

Thanks for the comment. Always very good to hear from you.

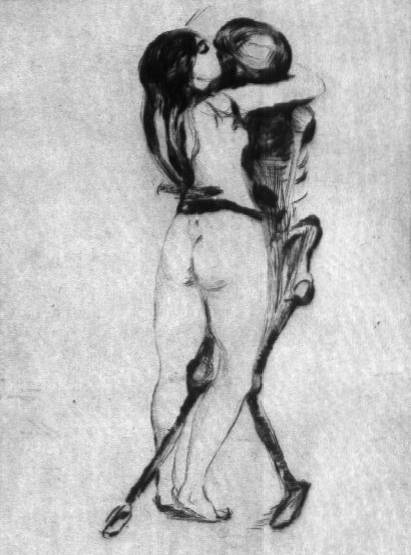

Thank you for including the Edvard Munch artwork, it has always fascinated me.

Schubert, he’s a handful.