‘Tears of Rage‘ (The Basement Tapes, Take #1, from the Columbia”The Bootleg Series” 2014)

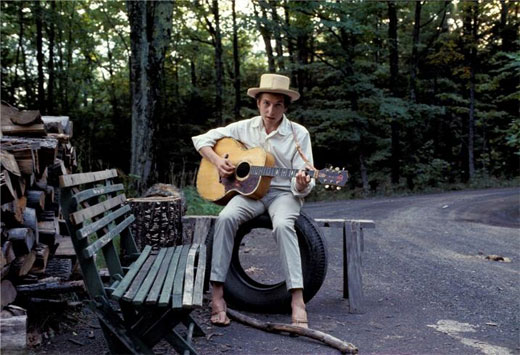

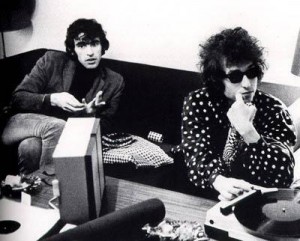

In the Summer of Love, 1967, while the Beatles were busy overtracking “Sgt. Pepper”, Bob Dylan was holed up in the basement of a pink house in upstate New York with a bunch of friends, playing hokey old country and western music standards at a leisurely tempo while he convalesced from a motorpsycho-broken neck.

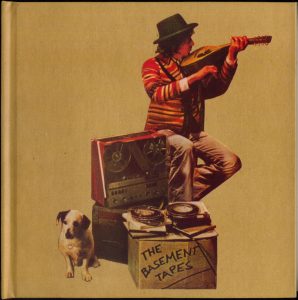

Fortunately, Dylan and his touring-band buddies, The Hawks (later The Band), turned on a home tape recorder. The resulting “Basement Tapes” – a collection of songs which are hilarious, wise, passionate, and pained, and include several grave masterpieces – leaked out as the very first illegal bootleg records (“The Great White Wonder”, “The Troubled Troubadour”–I owned and treasured them both), and here and there in minor cover versions. Then a year later The Band recorded definitive versions of the three most serious songs on their first album “Music from Big Pink” (‘This Wheel’s on Fire’, ‘I Shall Be Released’, ‘Tears of Rage’). For an incredible, picaresque story about the house itself, see SoTW 049.

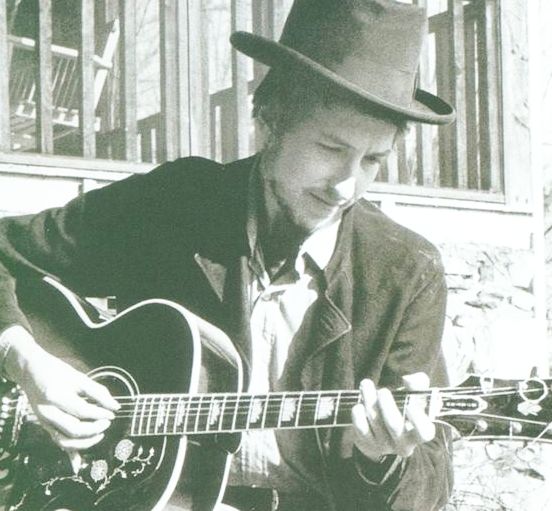

So “The Basement Tapes” had no direct impact on America when they were recorded in 1967. But they are The Watershed, the point at which the dominant aesthetic of the Western world turned from the supersonic to the simple. These recordings were seminal in shaping the way people view the world till today. They contained the seed for the mindset of the ‘organic’, the acoustic, the spiritual. “Strap yourself to a tree with roots, you ain’t going nowhere.”

June, 1966, America was exploding. Over 500 American soldiers died in Vietnam that month, the first race riots were breaking out in the Black ghettos of Chicago and other cities. Sympathizers of the nascent counterculture were listening to the new releases “Freak Out!”,” Yesterday and Today” (including the original release of ‘I’m Only Sleeping’, ‘Doctor Robert’, and ‘And Your Bird Can Sing’), “Aftermath”, “Daydream”, the debut albums of Love and the Mamas and the Papas.

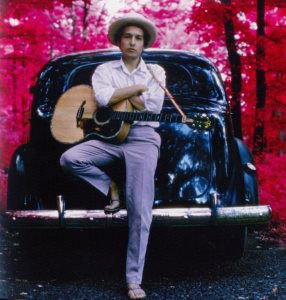

But the acknowledged leader of the pack was Bob Dylan, popularly proclaimed ‘prophet of the generation’, despite all his disclaimers. He was touring at breakneck speed with his new electric band, rabidly booed by dozens, listened to passionately by thousands. “Blonde on Blonde” was released on June 27, shouting “Everybody must get stoned!” Dylan practiced what he preached, ingesting large quantities of amphetamines and “who-knows what else”. Two days later he broke his neck in a motorcycle accident and disappeared from the public eye for a year and a half, till the release of “John Wesley Harding” in December, 1967.

Critic Mike Marqusee: “At the very moment when avant-gardism was sweeping through new cultural corridors, Dylan decided to dismount. The dandified, aggressively modern surface was replaced by a self-consciously unassuming and traditional garb. The giddiness embodied, celebrated, dissected in the songs of the mid-sixties had left him exhausted. He sought safety in a retreat to the countryside that was also a retreat in time, or more precisely, a search for timelessness.”

The Basement Tapes are rough, unpolished, rehearsal recordings. That’s okay. Perhaps it’s part of their charm, their intimacy. Many of Da Vinci’s greatest masterpieces have reached us only as sketches, right?

Guitarist Robbie Robertson: “One of the things is that if you played loud in the basement, it was really annoying, because it was a cement-walled room. So we played in a little huddle: if you couldn’t hear the singing, you were playing too loud.”

Organist Garth Hudson, “We were doing seven, eight, ten, sometimes fifteen songs a day. Some were old ballads and traditional songs … but others Bob would make up as he went along. … We’d play the melody, he’d sing a few words he’d written, and then make up some more, or else just mouth sounds or even syllables as he went along…It amazed me, Bob’s writing ability. How he would come in, sit down at the typewriter, and write a song. And what was amazing was that almost every one of those songs was funny.” Well, many of them. Not ‘Tears of Rage’.

Columbia Records released a 2-LP “The Basement Tapes” in 1975, questionable both in its audio quality and in its selection. A third of the tracks weren’t connected to Dylan, and a number of the major songs were omitted. In the 1990s a 5-CD bootleg set surfaced, “The Genuine Basement Tapes”, which includes virtually all the recordings from those months.

“Million Dollar Bash”:

But my mind always goes back to bootleg where I learned the core great songs from the session. There was a series of hilarious, comic psychodelerious virtuoso romps: ‘Million Dollar Bash’, ‘Open the Door, Homer’, ‘Yeah Heavy and a Bottle of Bread’, ‘Please Mrs Henry’, ‘Lo and Behold’, ‘Tiny Montgomery’. Just one taste: “Well, I looked at my watch, I looked at my wrist, I punched myself in the face with my fist. I took my potatoes down to be mashed, then I made it over to that million dollar bash.”

And there’s a series of brilliant, inspired songs flitting between the comic and the fantastic and the oh-so-serious: ‘Nothing Was Delivered’, ‘Quinn the Eskimo’, ‘Too Much of Nothing’, ‘Crash on the Levee’, ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere’. The last of these is ostensibly humorous. But there was enough gravity in it to serve as a catalyst for a 180° change in my life, no exaggeration. We took our music seriously back then.

“You Ain’t Going Nowhere” (improvised lyrics):

And there’s no music more serious than the three songs from that basement that The Band would record for their first album: the cosmic, apocalyptic ‘This Wheel’s On Fire’; ‘I Shall Be Released’, Dylan’s existential meditation on that little question: ‘What is the point of living a life of such pain?’; and our SoTW, ‘Tears of Rage’, a searing cry of the pain of betrayal.

If ‘I Shall Be Released’ is Dylan’s “Hamlet”, ‘Tears of Rage’ is his “King Lear”. Before this, Dylan had never collaborated. But bassist Rick Danko provided the music for ‘This Wheel’s on Fire’, and pianist Richard Manuel the music for ‘Tears of Rage’.

Manuel: “He came down to the basement with a piece of typewritten paper … and he just said, ‘Have you got any music for this?’ … I had a couple of musical movements that fit … so I just elaborated a bit, because I wasn’t sure what the lyrics meant. I couldn’t run upstairs and say, ‘What’s this mean, Bob: “Now the heart is filled with gold as if it was a purse”?‘”

I sure empathize with Richard. For most of my life I’ve been as puzzled by the lyrics to the song as I am moved by them. A strange thing, poetry–you can puzzle at it and puzzle at it, decade after decade, and you know you’ll never ‘solve’ it. If you could, if there were a Hidden Answer in there, it wouldn’t evoke that curiosity, that obsessive probing and plumbing and pondering.

Dylan has some great songs that can be parsed as allegory, stories directly paralleling something else–‘Mr Tambourine Man’ (a drug dealer), ‘Went to See the Gypsy’ (Elvis), ‘Ballad of a Thin Man’ (a straight guy at a gay party). But most of his great, evocative works defy such ‘solutions’. What does ‘As I Went Out One Morning’ mean? Well, who knows? And we’ll only diminish it by trying to tie it down to a specific reading.

Dylan himself wrote a wonderful, wise spoof on ‘solving’ his lyrics as the liner notes to “John Wesley Harding”. I heartily recommend reading them. Nonetheless, I’m going to try to provide a running reading of ‘Tears of Rage’ not as a Cymbal symbol, but as scaffolding, a reading which will help us examine it closely, but needs to be dissembled when the work is through.

We carried you in our arms on Independence Day

And now you’d throw us all aside and put us on our way.

Oh what dear daughter ’neath the sun would treat a father so–

To wait upon him hand and foot and always tell him, “No?”

A father addressing his daughter. His love is total, his intentions are pure. He will carry her in his arms to take her to participate in a public celebration of communion and community. She, in turn, fulfills her filial duties–but mechanically, denying him the love he has so unselfishly bestowed on her. With the cruelty of coldness, she won’t even leave him room to complain: ‘I do what is required of me by custom and tradition. But the most important thing can’t be legislated, and that you will not get from me.’ Why? What would move her to reject his love, to turn her back on his paternal dedication, to deny requiting him his unreserved dedication to her? There is no answer provided, only the acutest of pain, that of a child’s rejection, the betrayal of unadulterated trust and unbounded love.

Tears of rage, tears of grief, why am I always the one who must be the thief?

Come to me now, you know we’re so alone, and life is brief.

What is he seeking that will impoverish her? Will she be diminished by returning his love? Au contraire. So why? The father is left with no avenue for response. It is a question which can’t be asked, let alone answered. Love cannot be dictated or demanded. The pain of senseless, inexplicable rejection. The speaker can only cry, rage, grieve, pitifully plead. He has no other response available to him.

We pointed out the way for you to go and scratched your name in sand,

Though you just thought it was nothing more than a place for you to stand.

I want you to know that while we watched you discover there was no one true

That I myself, I remember now, thought it was it was a childish thing to do.

Our narrative strains here. Who is the ‘we’? It seems to extend beyond the narrator (and the mother). The community in its role as educator? The amorphous society at large? The pointer they give her seems genuinely altruistic, if transitory. She misperceives it. It is a means, she understands it only as an end. The observers are accused of being childish—were they mockingly waiting for her to be disillusioned? Why is the loving father associating with a less-than-loving ‘we’? Albeit he distances himself from them; but he had nonetheless been party to their cynical stance.

Tears of rage, tears of grief, why must I always be the thief?

Come to me now, you know we’re so alone, and life is brief.

Cry, Dad, cry.

It was all very painless when you ran out to receive

All that false instruction which we never could believe.

And now the heart is filled with gold as if it was a purse;

But, oh, what kind of love is this which goes from bad to worse?

Is this ‘instruction’ equated with the pointer from the previous verse, or contrasted with it? I could argue either case, and neither seems conclusive or convincing to me. In any case, a pyrrhic victory has been achieved: the heart is full of gold: her dutifulness. But the heart isn’t a purse, is it? It’s not gold that we’re seeking. It’s something much more precious.

Tears of rage, tears of grief, why must I always be the thief?

Come to me now, you know we’re so alone and life is brief

This love the father treasures so–“why is my desire for it unlawful?” he asks himself. “What is my crime? I carried you in my arms, I ask for nothing in return other than a measure of the unconditional love I by nature gave you. But it is unnaturally denied me, and life is irretrievably passing.” Just as the love the father feels is more precious than gold, so the pain he feels is sharper than any physical blade. It is the pain of his inexplicable, senseless rejection.

Let’s take down the scaffold now. I don’t see the song as an allegory. When he wrote it, Dylan had only just become a father. He was presumably happy in his new marriage. So where did this come from? It’s been said that ‘Tears of Rage’ was the first expression of the pain of betrayal felt by many of America’s Vietnam war veterans, or by extension many of its young citizens. Perhaps this is the rejection being expressed, that of political disenfranchisement.

Who knows? Not Richard Manuel, not me, probably not Bob Dylan. But the song is nonetheless a work of profound passion, evocative of the deepest pain I can imagine.

Next week we’ll see how The Band reworked this sketch into a treatment incomparably more crafted, and no less impassioned.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy:

016: Bob Dylan, ‘Percy’s Song’

259: Chris Thile & Brad Mehldau: ‘Marcie’ (Joni Mitchell), ‘Don’t Think Twice’ (Dylan)

008: ‘I’ll Keep It With Mine’, Fairport Convention (Bob Dylan)

190: Bob Dylan, ‘Boots of Spanish Leather’

176: Chuck Berry, ‘Too Much Monkey Business’ (Bob Dylan, ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’)

248: Bob Dylan, ‘You Ain’t Going Nowhere’

201: Bob Dylan, ‘All Along the Watchtower’

262: Bob Dylan, ‘Went to See the Gypsy’ (“Another Self-Portrait”)

164: Bob Dylan, ‘Tangled Up in Blue’

204: Bob Dylan, ‘Idiot Wind’ (NY Sessions)

087: Bob Dylan, ‘Black Diamond Bay’

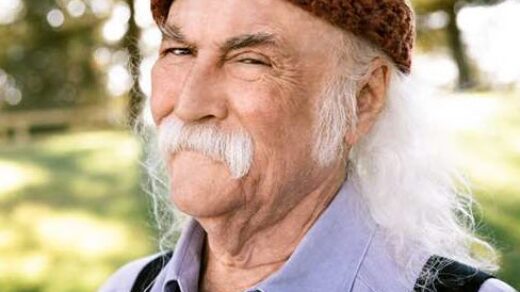

“I don’t mean to embarrass Bob or anything like that, but he’s said and done more, I think, than the lot of show business put together. You can take just one tune from back in the Sixties and it’s more meaningful than twenty or thirty years of what everybody else said, and yet he’s cranked out so many of them and said it with such insight and such wit – because that’s the thing I pick up from him, he’s really funny. And I suppose in a way he’s a hero of mine. But, at the same time, like with Ravi, I’m blessed in as much as being with them just makes life that much better”

George Harrison

(p. 202, Olivia Harrison, “George Harrison, “Living in the Material World”)

It is incorrect to state outright that Dylan broke his neck in ’67. He may have intentionally dropped out of the scene he was in; he may have entered treatment for drug abuse. He may even have had a motorcycle accident, the extent of which has always been inconclusive. Part of his myth has been that he nearly died in a motorcycle crash, but knowing his manipulation of his own imagery, we cannot trust his word on this. And, in fact, he has never spoken concretely about the accident, seeming uncomfortable to talk about it, as if it might be completely or partially fabricated.

I don’t call myself an authority on the details of Dylan’s life–there are people for whom that’s a full-time occupation. My understanding is that the period of his disappearance has never been conclusively or authoritatively documented, but the overall consensus of the several sources I looked at is that he had a motorcycle accident in which he hurt his neck.

Jeff, I think that you inflate the importance of this music. I like it but Dylan’s reputation rests on the work he did before this.

I’ve often marvelled that the idea that Dylan and The Beatles became outstanding figures for the work that they did for a few years in the early to mid-60s.

Beautifully written piece on the time The Band was being born, incubated by the Bob, who still had a lot to give.

God, how I miss those voices – Levon, Rick, and Richard. Dylan got them going, but Robbie sure picked up the baton and proceeded to write some of the greatest “American” music ever recorded. Comparing Big Pink and The Band albums to ANYTHING now is joke-worthy, if it wasn’t so sad.

Unique presentation and sound, incredible chops, killer songs, three heaven-sent voices, I mean…

Thank you for convincing me to finally listen to him and THEM after these decades…..he’s a wonder and Manuel….the VOICE.