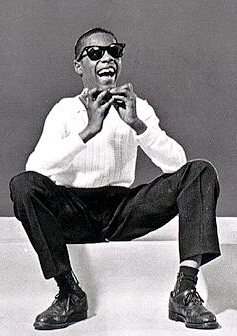

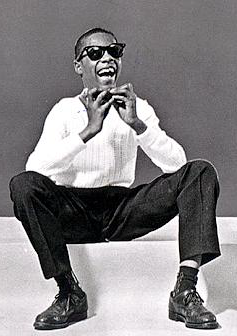

12-year old Stevie, ‘Fingertips’ (live video)

Have you ever thought about the relative personal-ness of the various wind instruments? It’s a subject that occupies me at various moments of repose. How much harder it is to get a personal tone on, say, a brass instrument (trumpet, valve trombone) than it is on a saxophone, for instance? Not that a brass player can’t express his personality on his ax; but it’s a whole lot harder to recognize a trumpeter from just a few notes than it is a saxophonist. A pianist is even harder. A glockenspielist may be even harder than that. A vocalist, obviously is the most individually expressive instrument, but God made that one, so it’s not really a fair competition. Anyway, it seems to me that running a close second to the human voice, and far ahead of the rest of the pack of wind instruments, is the harmonica.I think of the harmonicists I know best, and how their individual voices are as easily recognizable as my Aunt Martha’s (okay, her voice was indeed particularly strident) or Andy Devine’s. Toots Thielemans. John Sebastian. Bob Dylan. (I’m all too ignorant in the Little Walter/Sonny Boy Williamson genre.) And of course Mr Stevie Wonder.

Listen to this too-little known, quintessential James Taylor gem, ‘Don’t Be Sad’ from the too-little known James Taylor album “In The Pocket”. It’s co-written by the harpist. You don’t need me to tell you who that is.

Blind almost from birth (1950), Steveland Hardaway Judkins grew up as Steveland Morris in Detroit. He was discovered in a church choir by Ronnie White of the Miracles (SoTW 28, ‘The Tracks of My Tears’), who brought him to Berry Gordy at Motown, who signed him immediately and renamed him Little Stevie Wonder (“we can’t keep calling him the eighth wonder of the world”).

Blind almost from birth (1950), Steveland Hardaway Judkins grew up as Steveland Morris in Detroit. He was discovered in a church choir by Ronnie White of the Miracles (SoTW 28, ‘The Tracks of My Tears’), who brought him to Berry Gordy at Motown, who signed him immediately and renamed him Little Stevie Wonder (“we can’t keep calling him the eighth wonder of the world”).

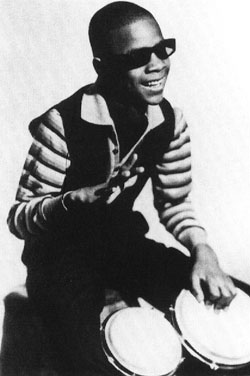

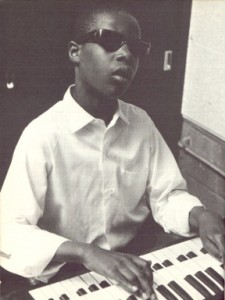

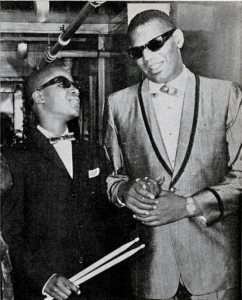

Within months, the eleven year-old Little Stevie had recorded two unsuccessful studio albums: “Tribute to Uncle Ray,” a derivative tribute to Ray Charles; and “The Jazz Soul of Little Stevie,” an instrumental showcase of Stevie’s prowess on bongos, harmonica and keyboards. It’s not all that memorable, but it is an admirable venture for the fledgling Motown/Tamla label. Here’s a harmonica ballad from there, ‘Some Other Time’.

![Jazzsoul[2]](https://jmeshel.com//wp-content/uploads/2011/07/Jazzsoul2-296x300.jpg) Then in May 1963 Motown released a live album, “The Twelve Year Old Genius,” which included a 6’40” almost-instrumental recorded in June, 1962, during a Motortown Revue performance at the Regal Theater in Chicago (with young Marvin Gaye on drums). Stevie plays a bit of bongos, shouts some very gritty call-and-response, lots of harmonica. And he plays some very memorable chromatic harmonica.

Then in May 1963 Motown released a live album, “The Twelve Year Old Genius,” which included a 6’40” almost-instrumental recorded in June, 1962, during a Motortown Revue performance at the Regal Theater in Chicago (with young Marvin Gaye on drums). Stevie plays a bit of bongos, shouts some very gritty call-and-response, lots of harmonica. And he plays some very memorable chromatic harmonica.

Here’s the entire original shmegegge, all 6’40” of it, Parts 1 and 2 undivided and unadulterated, in all their glorious funk.

Harmonicas are pre-tuned to a given scale, but the chromatic version has a handle which shifts the tone up one half step, enabling the musician to play all 12 notes, opening up a whole realm of tonal possibilities, a great number of which the 11 year-old covers here. Covers, my foot. He’s already inventing a personal style here, drawing heavily from contemporary rhythm and blues, especially Ray Charles, but also riding on the nascent Motown hit train, while infusing the music with his own personal ebullience, vibrant optimism, musical sophistication, and melodic genius which would come to fruition over the decades to come.

There haven’t been a lot of successful pop prodigies. Taylor Swift recorded her first album at 17. Here’s Michael Jackson at the age of 8; I hope I don’t need to explain why this underwhelms me. And here’s Little Stevie Wonder at 13 on the Motown Review – callow, perhaps, but certainly not innocent.

Rhythm and blues was born of the unholy coupling of gospel and the profane. There’s a fervor brewing here that may have begun on the altar in the church choir, but reached its pitch afterwards up in the balcony with some willing young soprano. If you don’t believe me, check out this prepubescent (well, maybe) version of Ray Charles’ ‘Hallelujah I Love Her So’. The lad knows of whence he sings.

Rhythm and blues was born of the unholy coupling of gospel and the profane. There’s a fervor brewing here that may have begun on the altar in the church choir, but reached its pitch afterwards up in the balcony with some willing young soprano. If you don’t believe me, check out this prepubescent (well, maybe) version of Ray Charles’ ‘Hallelujah I Love Her So’. The lad knows of whence he sings.

Here’s Brother Ray performing his version live in 1955, at the age of 25.

Pop records of 1963 were limited to three minutes, so Berry Gordy divided up the live version into Little Stevie’s first single, ‘Fingertips Part 1’ b/w ‘Fingertips Part 2′. In August, 1963, the B side hit #1 on both the Pop and R&B charts, only Motown’s second #1 hit, following The Marvellettes’ ‘Please Mr. Postman’. In the following decade, they would chart over 30 #1 hits, over 100 in the Top Ten. Their house band, The Funk Brothers, would play on more number one hits than the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, Elvis, and the Beatles combined. But rarely did the more mature Motown artists display the rawness and grittiness of 11 year-old Little Stevie – Martha and the Vandellas (‘Heat Wave’) being the only one that comes to my mind.

Little Stevie himself hit a bit of a dry spell as the hormones kicked in and his voice changed. In 1964 he appeared in the Frankie Avalon/Annette Funicello vehicles “Muscle Beach Party” and “Bikini Beach” (compulsory viewing for anyone remotely interested in that decade), singing such non-wonders as ‘Dance and Shout‘ (introduced by Don Rickles). Then in 1966 he recorded ‘Uptight (Everything’s Alright)‘, magnificient, albeit straight from the classic Motown mold of the time.

It wasn’t till 1972, a whole new era, when Stevie Wonder (no longer ‘Little’) began recording the series of albums including “Talking Book”, “Innervisions” and “Songs in the Key of Life” that gained him his reputation as one of the premier popular artists of our times.

It seems to me that there’s an element of minstrelsy in Little Stevie Wonder’s live performance of ‘Fingertips‘ (not to mention that in ‘Bikini Beach’) – buffoonish and groveling, yet musically gifted and joyous. I don’t think these displays of self-debasement can be dismissed as a function of Stevie’s youth; but rather they reflect stereotypes still extant in American society in the early 1960s, even in the self-perception of blacks. By 1972, due in no small part to the mature achievements of artists such as big Stevie Wonder himself, these vestiges had greatly disappeared. But that’s a wholly other story.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy:

SoTW 062: Martha and the Vandellas, ‘Heat Wave’

I’ve been known to listen to “Uptight” on a constant loop just to get to those soaring horns and that second verse. Thanks for this post!

Great post!

The new format is excellent

Is it fair and accurate to consider Stevie Wonder a pop music “genius?”

I love little Stevie on harmonica- a wonderful way to begin this Friday morning. Thanks!

“Genius” goes well with over-the-top multi-talented artists like Ray Charles, Stevie, or Jacob Collier. I think he’s an exceptional musician and songwriter. I don’t think his lyrics or songs as an entity are on the level with his melodic and arranging brilliance. Yeah, what the heck, let’s give him the moniker.

I’ve always had a soft spot for this “harp.” It’s wistful quality has a bittersweet taste I love. Genius? I was eighteen the first time I heard “Talking Book.” I thought it was genius then and for me, the word still apples.

Thank you for sharing your insights into his formative years.

Great post and what a great website you’ve got! Love it!