I try to confine myself in SoTW to music I enjoy and admire. I figure there’s so much great music waiting to be praised, why occupy ourselves with anything else? But I admit that this week, it’s not the music but the story behind it that moves me. Holocaust Day is about to begin, and here’s the stranger-than-fiction story of a Jewish composer from Eastern Europe.

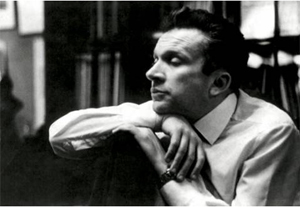

The personal odyssey of Mieczyslaw Weinberg (1919–1996) is emblematic of that of the Jewish people in the 20th century, not only for the trials and tribulations he underwent (although there were more of them than can be grasped), but because of the wholly bizarre, tortuous and miraculous course of events.

Before we get started with this tragic saga, a word about the man’s names. In Polish (i.e. prior to his move to the USSR), his name was rendered as ‘Mieczysław Wajnberg’. In the Russian it became ‘Моисей Самуилович Вайнберг’ (Moisey Samuilovich Vaynberg). In the Yiddish theater of antebellum Warsaw he was known as Moishe Weinberg (Yiddish: משה װײַנבערג). Among close friends he would also go by his Polish diminutive ‘Metek’. Re-transliteration of his surname from the Cyrillic alphabet (Вайнберг) back into the Latin alphabet produced a variety of spellings, including ‘Weinberg’, ‘Vainberg’, and ‘Vaynberg’. The form ‘Weinberg’, an English-language rendition of this common Jewish surname, is now the most frequently used form.

Weinberg’s father Shmuel (Shmil) left his home in the Moldavian town of Kishinev after the pogroms of 1903 and 1905 in which both his father and grandfather were killed (fired by a blood libel, in which The Jews were accused of murdering a Christian boy to use his blood in the baking of matzos for Passover). In Warsaw the Weinbergs joined the Yiddish theater, Shmil as a violinist and conductor, Sonia as an actress. The father gave his prodigy son his initial practical experience, exposing him to the traditional and liturgical Jewish music that was to inform his work for the rest of his life – a life already impacted by family history such as Moishe’s cousin Isay Abramovich Mishne, the secretary of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Baku Soviet commune who was executed in 1918 along with the other 26 Baku commissars.

Moishe made his first public appearance as a pianist at the age of ten, and two years later, in 1931, he became a student at the Warsaw Academy of Music. Moishe, or ‘Metek’, had time to compose a number of works (while working to support the family after the Yiddish theater had closed) before he graduated in 1939. Soon after the German invasion in September, his parents and sister were interned in the Lodz ghetto and murdered in the Trawniki concentration camp. Mieczysław managed to flee. He was stopped by a border guard who insisted on registering his name as “Moisey”, to mark him as a Jew, to which Weinberg replied: “Moisey, Abram, whatever you want, if I can only enter the Soviet Union!”

In Minsk, Belarus, he studied composition in the conservatory for two years. On the day after his final examinations in June, 1941, Germany invaded the USSR, and Weinberg again fled eastwards, this time finding work as a coach in the opera house in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

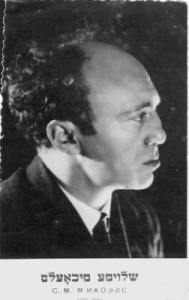

There he met Solomon Mikhoels (and married his daughter Natalia Vovsi), who served Stalin first as the artistic director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater, and then during the war as the chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. In this capacity he travelled around the world, meeting with Jewish communities to encourage them to support the Soviet Union in its war against Nazi Germany. After the war, Stalin became virulently anti-Semitic. Mikhoels was the most visible and respected Jewish intellectual in the USSR, so instead of receiving a show trial for his service to the state, in 1948 Stalin had him bludgeoned to death and his body run over by a truck as a thinly-veiled hit-and-run accident. Mikhoels received a state funeral.

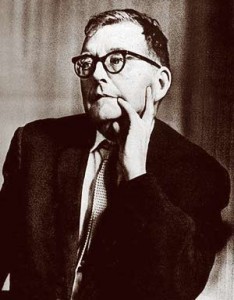

Meanwhile, back in Tashkent in 1943, Mikhoels encouraged his new son-in-law to send the score of his First Symphony to Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975), who was so impressed that he arranged for Weinberg to be officially invited to Moscow (an extremely rare occurrence), where he would remain for the rest of his life. Life in Moscow in 1943 had a lot of advantages over that in Uzbekistan–like food. Shostakovich was a cultural icon with a complex relationship with the establishment. He had already been denounced in 1936 (and subsequently rehabilitated). But he was to have many more ups and downs with the authorities over the years. Shostakovich (a philo-Semite) was a man of great personal courage, and had a great admiration for the younger Jew. Over the decades, Shostakovich used Weinberg as his first reader. He would bring him all his new compositions, discuss them. He greatly valued Weinberg as a musician, as a composer (much more so than did the critics and the public, who often dismissed him musically as a Shostakovich clone), and as a friend.

Shostakovich was denounced again in 1948 for Formalism. Most of his works were banned, he was forced to publicly repent, and his family had privileges withdrawn. He waited for his arrest at night on the landing by the lift, so that his family wouldn’t be disturbed.

At the time, although Weinberg refused to join the Communist Party, his music was officially praised “for depicting the shining, free working life of the Jewish people in the land of Socialism.” But even that didn’t help. He was arrested in January 1953 and charged with conspiring to establish a Jewish republic in the Crimea — a concoction that although absurd, was still accompanied by a death sentence. The real reason for his arrest was the fact that his wife was the niece of Miron Vovsi, the main defendant at Stalin’s anti-Semitic ‘Doctors Plot’ trial. It was assumed that the sickly Weinberg, incarcerated in sub-zero temperatures and deprived of sleep and clothing, would not return. It was likewise assumed that Weinberg’s wife would be arrested. Shostakovich and his wife agreed to accept power-of-attorney for the Weinbergs’ seven-year-old daughter Vitosha.

Then, in an act of incomprehensible courage, the out-of-favor Shostakovich wrote to Stalin and to NKVD security chief, Lavrenti Beria, protesting Weinberg’s arrest. A month later Stalin died, and many intellectuals and artists were released from prison, including Weinberg. He was officially rehabilitated shortly afterwards. Weinberg’s wife:

“Soon after this Shostakovich and his wife went to the south on holiday, making me promise to send a telegram as soon as Weinberg was released. And shortly we were able to send them this telegram: ’Enjoy your holiday. We embrace you, Tala and Metak.’ Two days later the Shostakoviches were back in Moscow. That evening we celebrated. At the table, festively decked out with candles in antique candlesticks, Nina Vasilyevna read out the power of attorney that I had written. Then Dmitri Dmitriyevich got up and solemnly pronounced, ’Now we will consign this document to the flames,’ and proposed that I should burn it over the candles. After the destruction of the ’document’, we drank vodka and sat down to supper. I rarely saw Dmitri Dmitriyevich as calm, and even merry, as he was that evening. We sat up till the early hours of the morning. Nina Vasilyevna laughingly recounted how I was worried that Vitosha would get a bad upbringing in the orphanage; it was then that I discovered that they had decided to take her into their own home.”

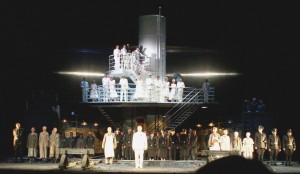

But Weinberg’s personal response to the attacks on himself and those close to him remained stoic and positive. Among his prolific output in almost every musical genre are 17 string quartets and 26 complete symphonies, the last of which, “Kaddish”, was written in memory of the Jews who died in the Warsaw Ghetto. Weinberg donated the manuscript score to the Yad Vashem memorial in Israel. In 1968 he wrote “Die Passagierin“, a ‘shatteringly intense’ opera with a libretto based on the novel of the same name by Zofia Posmysz, a native of Krakow who survived three years in the Nazi horror factories of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Ravensbrück. Weinstein considered it to be the most significant of his compositions, although he never heard it performed. The opera was only premiered in 2010; Director David Pountney brought Posmysz to the stage.

Two months before his death in 1996, dispirited by Russia’s disregard for him and weakened by a long battle with Crohn’s disease, Weinberg converted to the Russian Orthodox Church. Weinberg: “Many of my works are related to the theme of war. This, alas, was not my own choice. It was dictated by my fate, by the tragic fate of my relatives. I regard it as my moral duty to write about the war, about the horrors that befell mankind in our century.”

While I can’t say I identify with his response to the life forced upon him, I can’t help but be moved by the life itself.

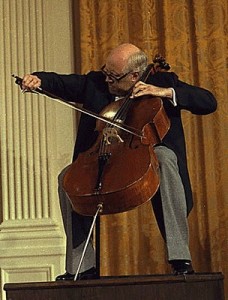

Here’s the first movement (Adagio) of his Cello Concerto Opus 43, as performed by the masterful and muscular Mstislav Rostropovich.

String Quartet #16 in Ab Minor, Op. 130 – I Allegro

String Quartet #7 in C Major, Op. 59 – I Adagio

Piano Sonata Op. 46 I Allegretto

If you liked this post, you may also like:

084: Dmitri Shostakovich, Prelude & Fugue No 16 in B-flat Minor (Tatiana Nikolaeva)

Thanks Jeff. A very sad and moving tale indeed and how appropriate for Yom Hashoah.

Yes a very depressing life.

Concerning Weinberg and his music … the more I dive into it the more I marvel about it. One stellar example (among many) is the cello concert performed by Rostropovich.

It was very nice to discover your page about Weinberg featuring his genial cello concerto. I use same music at my website. I could also encourage you and others to hear Rostropovich’s former student and fabulous cellist, Josef Feigelson playing his outstanding solo works: unique 24 Preludes and Four Sonatas – most music for unaccompanied cello ever written by one composer! Get it on Amazon or elsewhere…

I’m pretty sure I’d commit suicide if I listened to a lot of either Weinberg’s or Shostakovich’s music, but I found their story as you presented it quite inspiring.

“in an act of incomprehensible courage”. That’s quite a tribute. Shostakovich is the hero of this piece.

Paul Robeson also wrote to Stalin — in this case to save Itzik Pfeffer — but when Stalin did nothing, Robeson (notoriously) hushed it up.

http://www.conservapedia.com/Paul_Robeson#Betrayal_of_Pfeffer