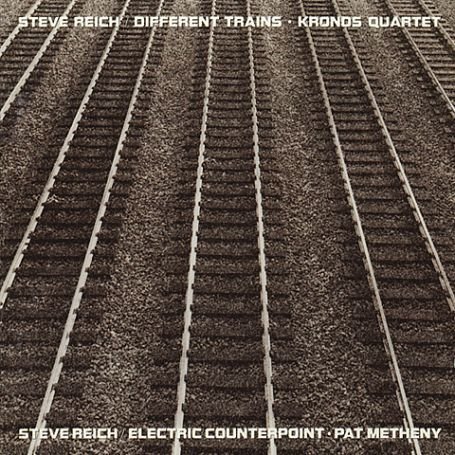

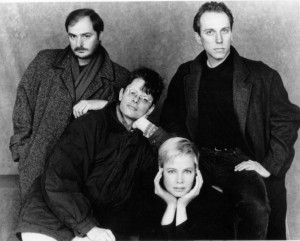

Different Trains — The Kronos Quartet

America-Before the War – Movement 1:

Europe-During the War – Movement 2:

After the War – Movement 3:

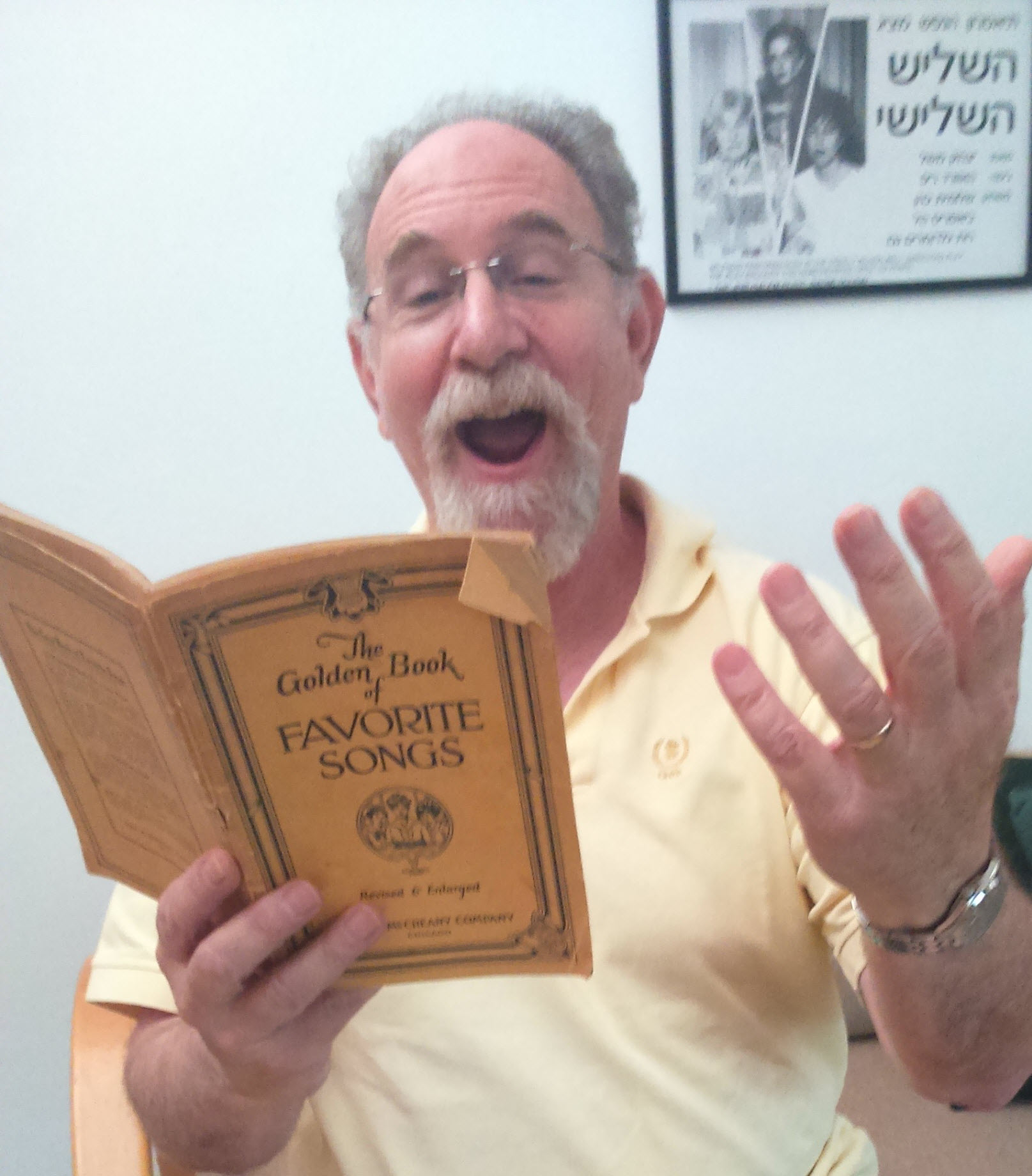

Need one apologize for listening tastes? You can listen to Justin Bieber or ‘Lawrence Welk Plays Your Polka Favorites’ all you want, I don’t care. I wish you wouldn’t tell me about it, but I don’t deny your democratic or aesthetic right to do so.

So I’m not going to apologize for the fact that in recent months I’ve become quite engrossed in Minimalist music. I realize this may not do much for my popularity at school or for the ratings of this blog, so maybe next week I’ll write about The Four Tops’ “I Can’t Help Myself”, just to keep the Hit-o-Meter popping. Aware of the dangers, this week I’m going to share with you the unique experience I’ve been having with Minimalist music, specifically that of Steve Reich, specifically his composition “Different Trains”.

I admit that my tastes can run at times to the arcane, the rarified, the–well, let’s call a spade a spade–the weird. I really don’t think that Steve Reich’s “Different Trains” is for everyone, but it has been speaking very loudly, clearly, and affectively to me (and it did win a Grammy), so I want to share it with you. Here come some boring definitions:

‘Minimalism‘ is often applied to designate anything which is spare or stripped to its essentials. Minimalism began as a post-WWII movement in visual arts where the work is stripped down to its most fundamental features; it expanded to encompass a movement in music which features repetition and iteration. The term has been used to describe a trend in design and architecture (Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: “Less is more”) wherein the subject is reduced to its necessary elements, often employing functional elements for aesthetic purposes (Buckminster Fuller). It has also been associated with Japanese traditional design and architecture; with the plays of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the writing of Ernest Hemingway, James M. Cain, Jim Thompson, and Raymond Carver, with poet William Carlos Williams; and even with the automobile designs of Colin Chapman.

Hey, I know almost all of those! (Well, I picked mostly ones I know, and I’m sure going to check out that Colin Chapman guy.)

‘Minimalist music‘ began in the 1960s as an underground contemporary classical scene in New York and San Francisco, based mostly on “consonant harmony, steady pulse (if not immobile drones), stasis or gradual transformation, and often reiteration of musical phrases or smaller units such as figures, motifs, and cells. It may include features such as additive process and phase shifting.” [We may not know all of those terms, but we get the gist, don’t we?] The composers associated with it are John Cage, Terry Riley, La Monte Young, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. Strong Minimalist elements can also be found in contemporary classical music employing traditional stylistic elements, such as that of Arvo Pärt (‘Holy Minimalism’) and John Tavener (‘Mystic Minimalism’), and even reaching back to composers such as Eric Satie, Carl Orff and Anton Webern.

New Age and much World music certainly huddle under the Minimalist umbrella. In jazz this aesthetic is rife; there’s even an entire label, EMC, dedicated to minimalist music.

[Here comes the neat part!] Minimal music is also present in pop music. Psychedelic rock acts of the 1960s and 1970s used repetitive structures and droning techniques to express the hallucinations of LSD and other drugs in a musical language. The Velvet Underground’s John Cale had an especially close working connection with La Monte Young. Minimalism also impacted Progressive Rock [a genre I’ve studiously avoided over the years], in artists such as Soft Machine, King Crimson, Brian Eno, Robert Fripp, Mike Oldfield and Tangerine Dream.

[Here comes the REALLY neat part!] In the 1990s Trance dance music was largely influenced by minimalism, based on repetitive instrumental structures. A favorite of mine, the ultra-bizarre Antony and The Johnsons, exhibit a completely original style of art songs, what I’d call ‘tone poems’.

Meanwhile, back to Steve Reich (b. 1936). He studied at Cornell (thesis on Wittgenstein, whom he of course later set to music) and Julliard. While driving a cab for a living, jazz drumming for fun, and living with Phil Glass for company, he began composing experimental music in a variety of contexts in the 1960s. A lot of it employed sampling (which anticipated the emergence of hip-hop by decades) and ‘phasing’, a process whereby two tape loops lined up in unison gradually move out of phase with each other, ultimately coming back into sync. Here are some of his notable early works:

- ‘It’s Gonna Rain‘, a phased piece constructed out of a 13-second sample of a sermon by the minister Brother Walter.

- ‘Drumming’ (inspired by a journey to Ghana) was scored for four pairs of bongos, three marimbas, three glockenspiels, and voice.

- ‘Pendulum Music’ which consists of the sound of several microphones swinging over the loudspeakers to which they are attached, producing feedback as they do so.

But it’s not all just weird, I promise you. Well, it is weird, but it’s not just weird.

- ‘Music for 18 Musicians’, one of his seminal works, in a very fine live rendition

- ‘Clapping Music’ – one performer keeps a line of a 12-quaver-long (12-eighth-note-long) phrase and the other performer shifts by one quaver beat every 12 bars, until both performers are back in unison 144 bars later; here’s a live performance; and here’s a TOTALLY mind-boggling version using a loop from one of the great B-movies of all time, John Boorman’s 1968 “Point Blank”, with the incredible Lee Marvin and the even incredibler Angie Dickinson

In later years, Reich began to draw materials from his Jewish background, such as ‘Tehillim’ (Psalms).

And for our Song of The Week, we’re bringing to you ‘Different Trains‘, a three-movement piece for string quartet and tape (1988), which won the Grammy Award in 1990 for Best Contemporary Classical Composition. Snippets of recorded speech are used here as a melodic (rather than rhythmic) theme.

The piece is Reich’s attempt, as an American Jew, to explore the legacy for him of the European Holocaust – a theme that has occupied me greatly throughout my life.

Recorded spoken phrases of his governess, a retired Pullman porter, and various Holocaust survivors are interlaid with the playing of the astounding Kronos Quartet. Reich compares and contrasts (“America-Before the War – Movement 1”) his childhood memories of his train journeys between New York and California in 1939–1941 (he traveled between his parents, who were separated) with the very different trains (“Europe-During the War – Movement 2”) being used to transport contemporaneous European children to their deaths under Nazi rule; and then (“After the War – Movement 3”) with the Holocaust survivors talking about the years immediately following World War II.

A leading professor of musicology, Richard Taruskin, called it “the only adequate musical response—one of the few adequate artistic responses in any medium—to the Holocaust”, and credited the piece with earning Reich a place among the great composers of the 20th century. Reich has been described by The Guardian as one of “a handful of living composers who can legitimately claim to have altered the direction of musical history”, and critic Kyle Gann has said Reich “may be considered, by general acclamation, America’s greatest living composer.”

You can find the definitive version of ‘Different Trains’ by The Kronos Quartet at the top of this page. You might also want to check out this striking rendition of Part 2 by The Smith Quartet from a BBC broadcast, a much more straightforward explication of the Holocaust elements in the piece.

I understand that Steve Reich sells fewer albums than Arrowsmith, and that The Kronos Quartet won’t sell out Madison Square Gardens performing this piece. Nobody’s going to put them on the bill with Justin Bieber, probably not even with Wayne Newton.

But I also understand I’m not alone in finding this work riveting, profound and moving.

If you enjoyed this posting, you may also like:

012: Arvo Pärt, ‘Cantate Domino’

073: Erik Satie, ‘Gymnopédie No. 1′

084: Dmitri Shostakovich, Prelude & Fugue No 16 in B-flat Minor (Tatiana Nikolaeva)

SoTW is a non-commercial, non-profit venture, intended solely to promote the appreciation of good music. Readers are strongly encouraged to purchase the music discussed here.

“In the 1990s Trance dance music was largely influenced by minimalism, based on repetitive instrumental structures.”

Only Louder and even more painful to the ear!!!

Music without subtlety, intracy, witticism, strength, direction or aim, is not, in my humble opinion, worthy of the name.

sorry, intricacy.

INTERESTING… AS USUAL…

This is life-transforming music, people.

Listen up.

Loved this. Had no idea it was out there. Thx

I got my feet wet with Phillip Glass some years ago when a friend who was obsessed with his music took me to see Godfrey Ruggio’s 1982 film “Koyaanisqatsi.” It’s music I would have overlooked, but coupled with the haunting visuals of the film which explores technology vs. environment, the sound track is hypnotic and moving.

This, the sounds of the train whistle, the feeling of it barreling down the tracks, the voices, haunting, like a recurring dream from childhood.

I didn’t think it was going to matter to me at all.

It does.

Thank you for sharing it.

Thank you, Jeff, for sharing this music with me. The string voices in the ‘Different Trains’ become part of a haunting soundtrack togther with the spoken words. It may not sell like pop music, but it moved me.

I’ve been listening to Steve Reich since the early 80s, starting with his Music for 18 Musicians. Heard Tehillim performed at Orchestra Hall in Chicago in 1983. So odd to think that you need to quality or apologize for your interest. He’s one of the most interesting composers of the 20th century. I was lucky enough to hear a live performance of Drumming at SF Conservatory of Music, 45 minutes long. There are trance-like potentialities in music unrealized by most western composers, you leave the performance transformed and alive. (Videos of this piece on YouTube only capture an aspect of this piece.)

I doubt there’s adequate artistic response to the Holocaust but at least Different Trains avoids the usual clichés.