As our hearts weep with the innocent Ukrainian victims of Russian aggression, our thoughts turn to Dmitri Shostakovich, a courageous human being and a great composer who lived and worked under the shadow of Soviet oppression. (Photos from the Ukraine/Moldova border by Maya Meshel)

Shostakovich, Prelude in B-Flat Minor (Tatiana Nikolayeva) (1987 version)

Shostakovich, Fugue in B-Flat Minor (Tatiana Nikolayeva) (1992 version)

How I Got from Pop Pap to Bach’s ‘Well-Tempered Clavier’

In the late 1990s I went through a musical transmogrification. Prior to it, I knew American/British pop/rock music pretty thoroughly, from 1956 on up into the 1980s and 1990s, when I found precious little new music of interest. I found myself haunting Used LP stores, lying on a grimy carpet, crawling back under the stacks into the dusty bins of throwaways, looking for obscure vinyl gems of oblique interest, such as “Pete Best’s Greatest Hits Vol III” or “Petula Clark Sings Robert Johnson”. I said to myself, “Perhaps this seam is mined out, Jeff, and it’s time to broaden your horizons.”

To tell the truth, I was going through some other mid-life bumps, changing jobs and a lot more. I needed an aural detoxification program. Who does one turn to? Johann Sebastian Bach (1665-1750), of course. I spent over a year listening almost solely to ‘Art of the Fugue‘, ‘Musical Offering’, the Cello Suites, the Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, and the solo ‘piano’ repertoire: the English Suites, the French Suites, the Partitas, the Toccatas, the 2-Part Inventions and 3-Part Sinfonias, the Goldberg Variations, a great CD of atypical flashy virtuoso pieces called “Brendel Plays Bach”, and of course, ‘The Well-Tempered Clavier’.

To tell the truth, I was going through some other mid-life bumps, changing jobs and a lot more. I needed an aural detoxification program. Who does one turn to? Johann Sebastian Bach (1665-1750), of course. I spent over a year listening almost solely to ‘Art of the Fugue‘, ‘Musical Offering’, the Cello Suites, the Sonatas and Partitas for Violin, and the solo ‘piano’ repertoire: the English Suites, the French Suites, the Partitas, the Toccatas, the 2-Part Inventions and 3-Part Sinfonias, the Goldberg Variations, a great CD of atypical flashy virtuoso pieces called “Brendel Plays Bach”, and of course, ‘The Well-Tempered Clavier’.

How I Got to Shostakovitch

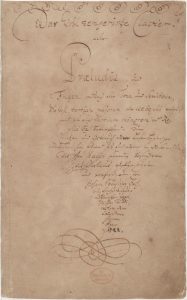

In Bach’s time, keyboard instruments (harpsichords and klavichords) were tuned to a specific scale (key)–C, F#, whatever. Theorists had come up with a scheme in which the keyboard would be tuned in equal intervals, a compromise solution which enabled playing in any key on a single instrument. Bach tried out such instruments, and composed two works to demonstrate their chops, “Das Wohltemperierte Klavier” Volumes I (1722) and II (1744), two cycles of 24 pieces, each one with a prelude and fugue, written in ascending order, major/minor. In other words, each one is constructed thus: C major prelude and fugue, C minor prelude and fugue; C# major prelude and fugue, C# minor prelude and fugue, etc. Together, the two books are known as “The 48” (2×24).

In Bach’s time, keyboard instruments (harpsichords and klavichords) were tuned to a specific scale (key)–C, F#, whatever. Theorists had come up with a scheme in which the keyboard would be tuned in equal intervals, a compromise solution which enabled playing in any key on a single instrument. Bach tried out such instruments, and composed two works to demonstrate their chops, “Das Wohltemperierte Klavier” Volumes I (1722) and II (1744), two cycles of 24 pieces, each one with a prelude and fugue, written in ascending order, major/minor. In other words, each one is constructed thus: C major prelude and fugue, C minor prelude and fugue; C# major prelude and fugue, C# minor prelude and fugue, etc. Together, the two books are known as “The 48” (2×24).

Sounds pretty dry, I admit, but artists have been employing artificial conventions as vessels for their inspiration since time immemorial (“Writing free verse is like playing tennis without a net”–Robert Frost), and Bach is Bach, and The 48 is one of the greatest works of art made by man.

So back in the late 1990s I listened to The 48 several trillion times, and was duly moved and transported and spiritually consoled. I used to view Bach as imposing arbitrary order on a chaotic world, eliciting sense out of disorder. I still do, actually. And then one day I happened upon an homage to The 48 written in the early 1950s by Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975).

So back in the late 1990s I listened to The 48 several trillion times, and was duly moved and transported and spiritually consoled. I used to view Bach as imposing arbitrary order on a chaotic world, eliciting sense out of disorder. I still do, actually. And then one day I happened upon an homage to The 48 written in the early 1950s by Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975).

How Shostakovich Got to the Well-Tempered Clavier through Tatiana Nikolayeva

Shostakovich was a thoroughly modernist composer who maintained a rocky relationship with the oppressive Soviet regime under which he lived. He was Russia’s most prominent composer, too well-known and respected to be sent to the Gulag or to be disappeared, although a friend testified in 1948 that “he waited for his arrest at night out on the landing by the lift, so that at least his family wouldn’t be disturbed.” He was twice denounced for anti-Socialist ‘formalism’ (in 1936 and 1948). He sometimes wrote personal pieces he knew could not be performed, sought professional refuge in teaching or writing for films or politically proper venues. For example, in 1939, Leningrad Party Secretary Andrei Zhdanov commissioned from him a “Suite on Finnish Themes” to be performed by the marching bands of the Red Army as they entered the conquered Helsinki. Shostakovich never claimed the composition as his own.

This same Zhdanov, who decided during the siege of Leningrad to give food to the defending army rather than to the starving populace, became Minister of Culture, Stalin’s right-hand man, and masterminded the post-war cultural purge. In 1950 he rehabilitated Shostakovich in order to humiliate him by sending him abroad as official representative of the Soviet Union. The event was a festival in Leipzig marking the bicentennial of Bach’s death, where Dmitri was a judge for the first International Bach competition. One of the competitors was a 26-year old pianist Shostakovich had met in Moscow, Tatiana Nikolayeva. She performed pieces from the Well-Tempered Clavier (which Shostakovich had played as a young piano student, although they had nothing of the stature they were to gain from the 1950s onwards) and won the gold medal.

How Shostakovich Composed His Own P&F Cycle

Back in the USSR (ouch!), Shostakovich was inspired to compose his own cycle of 24 preludes and fugues. These were dangerously personal pieces, but he was protected by the fact that Bach was perceived by the Evil Empire as a champion of the proletariat! According to the lengthy article on Bach published in 1973 in the Soviet Musical Encyclopedia, “The national and democratic tendencies of Bach’s creativity find their source in the protestant chorale. It was Friedrich Engels who described one of the most famous examples, Ein’ feste Burg is unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress Is Our God) as ‘the Marseillaise of the 17th century.’”

Shostakovich worked quickly, averaging only three days for each piece. As each was completed he would invite Nikolayeva to his Moscow apartment to show off his work. The complete work was written between October 10, 1950 and February 25, 1951. He dedicated it to her, and she premiered it in Leningrad December 23, 1952.

Here’s a wonderful 13-minute film, including interviews with Tatiana and rare clips), detailing the above story.

On a formal level, Shostakovich’s Opus 87 (not to be confused from his ’24 Preludes’ Op. 34) has significant differences from Bach’s 48. Here the compositions don’t move upwards in chromatic steps, but rather in relative major/minor pairs around the circle of fifths: C major, A minor, G major, E minor, D major, B minor, and so on – the same organization as Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s set of 24 preludes (1815) and Chopin’s and Joseph Christoph Kessler’s sets (both 1839, apparently a very good year for such cycles). Wikipedia, Music written in all major and/or minor keys

“In his Preludes and Fugues, Shostakovich never loses sight of the Bach model that inspired him, but still employs all the harmonic and other possibilities available to a mid-20th-century composer. Many of the pieces in the cycle possess an improvisatory, unfettered character; they are aware of tradition without being paralyzed by it. Shostakovich does not make obvious direct references to the Bach cycle. The preludes and fugues in each pair are more closely linked thematically and harmonically than is the case in Bach, and there is no pause between them in performance.” (Harlow Robinson).

“In his Preludes and Fugues, Shostakovich never loses sight of the Bach model that inspired him, but still employs all the harmonic and other possibilities available to a mid-20th-century composer. Many of the pieces in the cycle possess an improvisatory, unfettered character; they are aware of tradition without being paralyzed by it. Shostakovich does not make obvious direct references to the Bach cycle. The preludes and fugues in each pair are more closely linked thematically and harmonically than is the case in Bach, and there is no pause between them in performance.” (Harlow Robinson).

From the piece’s premiere till the 1990s–the same years I was listening to rock music–the only three recordings of real note were by Tatiana Nikolaeva, 1962 and 1987 (Melodiya) and 1991 (Hyperion). But since then the cycle has been widely recorded, perhaps two dozen versions, a very popular one by Keith Jarrett (which I feel lacks the gravitas of the Russian’s) and an audacious one by Finnish Olli Mustonen, who coupled Bach’s and Shostakovich’s pieces, interspersing them in order.

Here are recently released videos of Tatiana Nikolaeva performing Shostakovich’s 24 in 1992. Pt 1, Pt 2.

And here she is from 1962, a mere lass of 38, playing the entire cycle.

And here you can follow the score as Ms Nikolaeva plays the first 12 P&Fs.

Here’s Maestro Shostakovich himself tickling the ivories on 8 of the P&Fs, from about 1952.

Here’s the great Sviatoslav Richter playing 6 of them in 1963.

The critics say that Shostakovich’s Preludes and Fugues are personal, his refuge from the Mind Control of the Evil Empire. I find solace and inspiration in the music, in the courage of this great artist refusing to surrender to the totalitarian Soviet regime. While our hearts weep with the suffering of the Ukraine, our spirits are bolstered by this music as we pray for the wellbeing of the two million innocent Ukrainian refugees, men, women and children.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy:

SoTW 005: Toccata in Cm, JS Bach (Glenn Gould)

SoTW 077: ‘The Art of the Fugue’, JS Bach (The Emerson Quartet)

SoTW 113: J.S. Bach, ‘Prelude to Suite #2 for Unaccompanied Cello’ (Casals)

Very soothing. A musical balm.

thank you!

thank you indeed for highlighting this beautiful music.

Time to listento Alexander Melnikov. Especially P&F no 16

It acknowledges our dark places and at the same time, consoles and heals us.

Thank you for sharing the beauty.

Beautiful music and a beautiful sentiment.

Well done.

!טוב מאוד Yeyasher Kochacha!

Good Shabbos.