Bill Evans Trio – ‘Gloria’s Step’ (1st Take), from “The Complete Live at The Village Vanguard”

From the same album, ‘All of You‘ and ‘Waltz for Debbie’

Most mornings I started the day with Bill Evans. Not just any Bill Evans, but  “The Complete Live at The Village Vanguard”. Sometimes we play music to reflect our mood, sometimes to enhance it, to complement it or to change it. But between my first and second cups of coffee, when the world is just a pre-moodal blur, I can do whatever I want. So I almost invariably start with something easy on my ears, easy on my mind, easy on my soul. Like Brad Mehldau, for example, a 51-year old pianist, one of the best jazz artists around. And almost invariably, after a few minutes, I ask myself “Why not go for the original? It’s early, at this hour you don’t yet owe anybody anything, listen to whatever you want.” And if I’m feeling really indulgent or up or down or in the middle, I say, “Well, if we’re indulging ourselves, let’s go for the very best.” And there goes that 3-CD 1961 set, which gets us up to 10:00, on the cusp of our third cup of coffee, and the world has become a pretty tolerable place.

“The Complete Live at The Village Vanguard”. Sometimes we play music to reflect our mood, sometimes to enhance it, to complement it or to change it. But between my first and second cups of coffee, when the world is just a pre-moodal blur, I can do whatever I want. So I almost invariably start with something easy on my ears, easy on my mind, easy on my soul. Like Brad Mehldau, for example, a 51-year old pianist, one of the best jazz artists around. And almost invariably, after a few minutes, I ask myself “Why not go for the original? It’s early, at this hour you don’t yet owe anybody anything, listen to whatever you want.” And if I’m feeling really indulgent or up or down or in the middle, I say, “Well, if we’re indulging ourselves, let’s go for the very best.” And there goes that 3-CD 1961 set, which gets us up to 10:00, on the cusp of our third cup of coffee, and the world has become a pretty tolerable place.

I have a hard time filtering all the things I want to say about Bill Evans (1929–1980). For many years, this set has been the work I’ve listened to most, loved most, and appreciated most (and those are three distinct issues). It has moved me as few other works have – Bach’s Suites for Cello, Dylan’s “Blood on the Tracks”, James Taylor’s Apple album (a partial and admittedly disparate list) are the company it keeps in my soul.

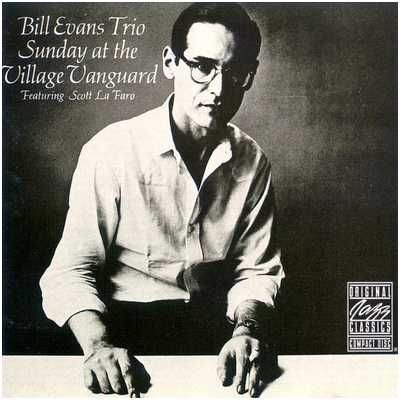

Bill Evans’ “Live at The Village Vanguard” can be perceived in several ways. It can sound like inoffensive cocktail music. It’s very ‘nice’, pleasant on the ear. And yet jazz fans know that in this performance Bill Evans reinvented the piano trio (the jazz equivalent of classical music’s string quartet), and in my opinion single-handedly changed our perception of rhythm in modern music, evolving it from the mechanical metronome to the sublime interplay of fluid improvisation. And on a whole different level, if you look at the album cover for one of the releases, you’ll see there was something harrowing going on below the surface.

Bill grew up as a ‘nice boy’ in New Jersey, graduated from Southeastern Louisiana University with a degree in classical piano performance. But that failed to hold his attention, because he sight-read music so well, was able to perform the classical repertoire at such a level of refinement from the git-go, that he failed to maintain the necessary edge to practice hard enough to make a career of it. He played a bit of jazz in New York, served in the army and in the late ’50s returned to the scene in New York, where he quickly made a name as a highly esteemed studio musician. Although record companies were interested in recording him, he made only two albums under his own name in five years – by his own choice, maintaining that he would record ‘when he had more to say’.

degree in classical piano performance. But that failed to hold his attention, because he sight-read music so well, was able to perform the classical repertoire at such a level of refinement from the git-go, that he failed to maintain the necessary edge to practice hard enough to make a career of it. He played a bit of jazz in New York, served in the army and in the late ’50s returned to the scene in New York, where he quickly made a name as a highly esteemed studio musician. Although record companies were interested in recording him, he made only two albums under his own name in five years – by his own choice, maintaining that he would record ‘when he had more to say’.

In 1959, Miles Davis became interested in exploring modal music and asked his mentor Gil Evans to recommend a pianist to join his working band, someone with a solid grounding in the European tradition and knowledgeable in musical theory. The resulting collaboration between Miles and Bill Evans was “Kind of Blue”, a universally acknowledged masterpiece, some say the seminal marriage of American jazz with the European tradition.

But Bill left the band shortly after that recording to pursue two main interests –the search for a trio which would express his unique musical vision, and the beginning of what would be a lifelong addiction to drugs, beginning here with heroin, later modulating to drink and cocaine till his death at the age of 51. But he achieved also his other goal, with the 25-year old drummer Paul Motian and the 23-year old bassist Scotty LaFaro.

Evans was seeking to evolve beyond the traditional piano trio format in which the bassist,  drummer and the pianist’s left hand all provided a predictable backdrop for the pianist’s right hand. He wanted to build a group of equal partners in creativity. In LaFaro, he found his musical soulmate. From the fall of 1959 till June 1961 they developed this new musical language together in two studio recordings, “Portrait in Jazz” and “Explorations”. In June, 1961, they went to the Greenwich Village jazz club The Village Vanguard for a week’s gig. Their producer, Orrin Keepnews, decided to record them on Sunday, because that included an additional matinee show (two sets, in addition to the regular three evening sets), giving him more material to choose from. Here’s Keepnews discussing the formation of the trio, here discussing the trio’s work on that legendary day.

drummer and the pianist’s left hand all provided a predictable backdrop for the pianist’s right hand. He wanted to build a group of equal partners in creativity. In LaFaro, he found his musical soulmate. From the fall of 1959 till June 1961 they developed this new musical language together in two studio recordings, “Portrait in Jazz” and “Explorations”. In June, 1961, they went to the Greenwich Village jazz club The Village Vanguard for a week’s gig. Their producer, Orrin Keepnews, decided to record them on Sunday, because that included an additional matinee show (two sets, in addition to the regular three evening sets), giving him more material to choose from. Here’s Keepnews discussing the formation of the trio, here discussing the trio’s work on that legendary day.

Like many great jazz recordings, the participants felt that it was ‘really good’, but had no sense of recording for posterity. Sixty years later, that day’s music is universally regarded by jazz fans as a unique work of genius and transcendent beauty. Ten days later, the car Scotty LaFaro was driving in upstate New York veered off the road and hit a tree, killing the driver. Distraught, Bill Evans sank into his heroin habit and stopped recording for a year.

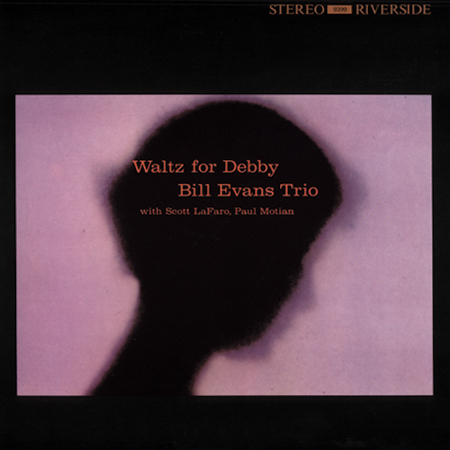

The first album released from the Village Vanguard sessions was called “Waltz for Debby”. Evans and Keepnews focused their selection on performances written by and featuring LaFaro.

“Sunday at the Village Vanguard” followed the same year, and some years later “Bill Evans – More from the Vanguard”. In 2005, the entire day’s recordings were released as a 3-CD set, “The Complete Live at The Village Vanguard”.

The rest of Evans’ career would follow an unusual trajectory. After a year and a half of depression during which Evans wandered around wearing Scott’s clothes and recording only one solo session, young bassist Chuck Israels dragged him out of his shell to form the second trio, with drummer Larry Butler. They recorded the sterling albums “Moonbeams” and “How My Heart Sings“, and a number of fine live performances on television. Evans then teamed with bassist Eddie Gomez and a series of drummers over the next 10 years. He also recorded in other contexts, most notably in duets with guitarist Bill Hall and several groundbreaking experiments in recording himself overdubbed in two or three parts (the Grammies didn’t know whether to give him the prize as solo or group artist). Ravaged by drugs, Evans somehow managed to maintain the highest levels of musical standards (to the point of one notorious performance where his left hand was rendered useless by the excesses of the needle, but he performed admirably right-handed). His followers are so dedicated that every scrap of his recordings is released commercially. I personally own and listen to well over a hundred CDs of his, even the relatively mundane years with Gomez.

Then incredibly, in 1979, he formed a new trio with two young musicians, Joe LaBarbera (drums) and Marc Johnson (bass). He developed a probing new style and recorded extensively, in a final burst of creative energy, right up to his death in 1980.

But nothing ever matched the magic of that Sunday in 1961. Nothing by Bill Evans, nothing by anyone else.

The songs that Bill Evans’ trio played that day are mostly standards (‘My Foolish Heart’, ‘All of You’, ‘My Romance’, ‘Some Other Time‘, ‘Detour Ahead’, ‘My Man’s Gone Now‘, ‘I Loves You Porgy’), with a scattering of originals–LaFaro’s ‘Gloria’s Step‘ and ‘Jade Visions’, Evans’ sublime ‘Waltz for Debby’. After much deliberation, I selected for our Song of The Week ‘Gloria’s Step‘ for several reasons. First, that was the first piece they played that day. Secondly, there’s a 10-second break in the middle where the tape recorder lost power, nearly causing the technical team heart failure. I think that interruption is fittingly emblematic of the truncated life of this trio and of the fragility of the moment of inspiration. But mostly, I chose it because of its innate beauty. I could describe at length the unusual, affective melody of the song, the revolutionary mid-keyboard blocked chords of Bill Evans’ left hand, the utterly and unutterably magic interplay between these three musicians. But I’d never do it justice. Because this is as beautiful as music gets, and no words can rival that.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

096: Bill Evans (solo), ‘Easy To Love’ 124: Bill Evans, ‘Nardis’ 094: Brad Mehldau, ‘Martha, My Dear’ (“Live in Marciac”)

Thanks. I enjoyed the posting. (Mind you, I was a bit surprised by the other albums that stayed with you). I’m listening to Intermodulation with Jim Hall right now. Even though it wasn’t on your list I ended up there.

Excellent and interesting article about the most unique, instatnly recognisable and and brilliant pianist. (BTW the guitarist was Jim Hall)

Hi…last time I stopped by here was about 11 years ago in response to your excellent essay on NARDIS.

Here I am back again…my introduction to Bill Evans was hearing that opening F major 7 chord from this recording. I was INSTANTLY mesmerized and became a devotee of Bill Evans’s music. LaFaro and Evans both had perfect pitch, but there’s more. Both had what I call an extremely long field of vision with respect to song forms. When many jazz players had a field of vision of eight or 12 bars, Evans and LaFaro both had a field of vision of one entire chorus. IMHO that’s why they meshed so well and always “met at the end of the form” regardless of what happened before that end. This tune sounds simple in the trio’s hands, but it is anything but simple. The opening phrases are FIVE measures long, a notable departure from standard song form. The B section could be seen as 10 bars long. That’s the first notable aspect of the song. Next are the chords–they are totally unique. No real ii-V progressions to speak of, but a series of descending major seventh chords and a one-bar turnaround to F minor 7. The B section is unlike any tune I’ve ever tried to play, with a hint of the NARDIS sound (Emi7=>Fmajor7 but followed by a series of half-diminished seventh chords…at the end of the B section are two bars of a chord ambiguous between E flat 7 and A 7, turning back to the original F major 7. Finally, the form overall is AAB. The complexity of this tune is masked by the incredible musicality of the performers. I have heard other groups try to play the tune but no group has ever approached the depth and insight of the original trio’s performance. I could say more, perhaps about the lydian flavor often used on the A section, but I’ll stop here and thank you again for your most perceptive writing. With this article, you’ve reminded me of a key inflection point in my relation to music.