There’s a plague outside a-raging, they say, so it’s hard to avoid thoughts of mortality. It’s starting to sink in, I really am going to die someday. Like my parents did. Like my kids will. Like my grandkids will. I can’t say I’m comfortable with that thought, but I am trying to get used to it.

I just heard that my favorite jazz musician, Lee Konitz, has passed away from the corona virus at 92. I can’t say I was shocked. But, boy, am I sad. I know, he went ‘the way of the world’—got born, did some stuff, died, just like all of us.

Lee Konitz’ music has enriched my life significantly. His music is part of the room I live in. For the past two years, I’ve been writing a novel and listening to Lee: one giant project for man, one insignificant scribble for mankind. But throughout, Lee has been for me a paragon of integrity, with his tenacious commitment to the very music itself—no concessions, no pandering, no shticks.

Then the corona virus got him. What can I say? I have no words. But I do have his music. I’m going to go listen to some Lee Konitz.

Rest Peaceful-lee.

***

A wonderful thing happened to me this week [JM: written in 2014].

I guess it’s pretty obvious that there’s nothing I enjoy more in the world than talking about music.

My hands-down favorite living jazz musician is the wise, wily, wizened Lee Konitz.

And this week I had the experience of a lifetime sitting for three hours and shmoozing with Lee about music.

I wasn’t at all star-struck talking to Lee. He’s a human being, 83 years old; and as the saying goes, he puts his pants on one leg at a time. He’s just a jazz musician, he’s not a star or anything. But he’s had an incredible career. Preparing for the meeting with him, I actually counted the number of Lee Konitz CDs in my collection. There are 91, beginning from 1947 as a kid soloing on the alto sax with the Claude Thornhill Orchestra; the Birth of the Cool sessions; the leading disciple of Lennie Tristano, the father of cool, intelligent modern jazz. And that just takes him up to the early 1950s.

He did great stuff in the 1950s, recorded relatively little in the 1960s (here in a wonderful, bizarre clip with the Tristano group, here with Bill Evans playing with one hand!, but in each decade since the 1970s his activity has increased, to the point where in the years 2000-2008, according to the All Music Guide data base, Lee released 34 new CDs under his name. New CDs.

He did great stuff in the 1950s, recorded relatively little in the 1960s (here in a wonderful, bizarre clip with the Tristano group, here with Bill Evans playing with one hand!, but in each decade since the 1970s his activity has increased, to the point where in the years 2000-2008, according to the All Music Guide data base, Lee released 34 new CDs under his name. New CDs.

And you have to understand, Lee Konitz isn’t some bloated old legend treading the same waters. He’s found himself a groove that is for me mind-boggling: constant experimentation, newness, challenge. An 83-year old waking up every single morning, saying “Ok, let’s see what new territories we can explore today.” My mind just doesn’t grasp that. Here are some amusing recent short clips of Lee talking about fame and fortune and music.

He says that he’s more popular today than he ever was, that he’s always being invited all over the world, and he likes playing with local musicians, that that refreshes him. This may be true, but he’s also constantly initiating new projects, new collaborations, new contexts. Someone should teach the guy that people his age are supposed to lose energy, not pick up speed.

Lee’s not a star. ‘He can walk down the street without being identified’? Let me tell you a little story. I’m sitting in the restaurant talking to him. I had taken out of my bag to make some point the fine critical biography “Lee Konitz” by Andy Hamilton. The man behind me bumped my chair when he stood up, turned around to apologize, and saw the book lying on the table.

“Oh, Lee Konitz!” he said. “I saw him last year in Louisville.”

“Oh, Lee Konitz!” he said. “I saw him last year in Louisville.”

“How was he?” I asked, straight-faced.

“Oh, he was really great!” the man replied.

“Well, this is him,” I said, pointing at my lunch partner.

“What?” said the Louisvillian.

“This is him. This is Lee Konitz, the man.”

“Oh,” said the Louisvillian. “Oh. But. I–. Uh–. Huh? Oh.”

So he can sit in a restaurant and not be recognized even by a fan. We’re not talking here Soulja Boy, Ashlee Simpson or Heidi Montag. (Just for the record, I googled ‘most popular musicians 2009’. I have no idea who these people are.)

Lee asked me, “You listen to so much of my music. What attracts you to it? What do you like about it?” I was very flattered to be asked such a question. Flattered and flustered. After I’ve had now a couple of days to collect my thoughts, I’d like to answer a bit more coherently. (I’ll mail him a copy of this. He doesn’t own a computer.)

We were talking about Kurt Elling, the Chicago jazz vocalist whom I admire greatly and Lee also respects. He won a Grammy award last week, and I told Lee that I was disappointed. ‘Why?’ he asked. ‘Because he won it for a CD that is aimed at popular reception, the music market, more than anything he’d done in the past, and I’m afraid his success will only draw him further towards pandering to popular tastes, away from a dedication to pure, honest musicianship’.

That’s what attracts me so much to Lee Konitz’s music. No gimmicks. Not in marketing, not in celebrity, and most of all not in music. Every single project, every cut, every note is honest, intelligent, restrained, refined, well-considered, responsible. There just aren’t many artists who bring such intelligence, honesty to the table—and at his best, married to very great passion. Lee isn’t always a romantic, but I suppose looking over all those 60+ years of great music-making that he’s done, I’d have to say that most of my favorites (though not all–there’s about 3 tons of his more difficult, abstract music that I find absolutely riveting) are those that balance the mind with the heart, his more emotionally expressive music. He’s always intelligent and honest, always an absolute master musician, and frequently invites his heart onto the stage with him.

Let me give you an example, one that we discussed at length in our meeting. In 1996, Lee (b. 1927) was scheduled to perform with fellow veteran bassist Charlie Haden (b. 1937). Charlie came from a country & western background, played in Ornette Coleman’s seminal free jazz quartet, and has recently made a series of ‘jazz noir’ CDs, revisiting the sounds and aesthetic of 1940s Hollywood B-movies. He’s known as a non-virtuoso bassist. No flashy solos, no grandstanding. In fact, he plays very few notes, frequently ‘on four’, just the first beat of the measure.

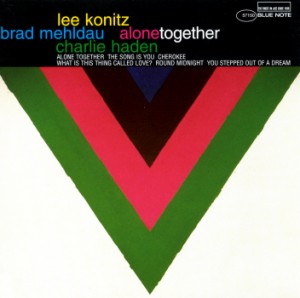

Lee was looking forward to the gig. “I thought I can finally play with someone I’m faster than. I had been working on becoming the slowest saxophone player around–I’m being serious. [If you want to hear just how untrue that is, check out classic Lee Konitz with Lennie Tristano circa 1949–JM] Anyway, Charlie called me a week before and said that Brad could use a gig.” Brad Mehldau (b. 1970) is young enough to be Haden’s son, Lee’s grandson. “I had never played with Brad, and didn’t really know how special he was. So here I was playing with another virtuoso, and I was a bit disturbed–it’s impossible for me to play faster than a piano player! But by the second set, Brad was listening and changing his playing, and I appreciated that very much… We ended up making three CDs in two days.”

Lee was looking forward to the gig. “I thought I can finally play with someone I’m faster than. I had been working on becoming the slowest saxophone player around–I’m being serious. [If you want to hear just how untrue that is, check out classic Lee Konitz with Lennie Tristano circa 1949–JM] Anyway, Charlie called me a week before and said that Brad could use a gig.” Brad Mehldau (b. 1970) is young enough to be Haden’s son, Lee’s grandson. “I had never played with Brad, and didn’t really know how special he was. So here I was playing with another virtuoso, and I was a bit disturbed–it’s impossible for me to play faster than a piano player! But by the second set, Brad was listening and changing his playing, and I appreciated that very much… We ended up making three CDs in two days.”

That’s what Lee’s all about, listening. No grandstanding, no virtuosity, no preconceptions or credos. Empathy. On this trio date, there was nothing planned. Lee just called out standards on stage. It seems to me that if you pay close attention to this music, you can hear the three musicians listening to each other. There’s an electrical magic in the silences. Three free-floating acrobats with no safety net. Every moment, the miracle of music being created out of a void, made into a coherent tapestry of magical beauty, right before our very eyes and ears.

Lee asked me what I liked so much about this CD. I told him it was the freedom from tempo, no forward driving beat, no obligation to get anywhere. The freedom to float and explore the moment. He said something like, “No, we were just listening to each other because we hadn’t played together before.” Maybe he was just being disingenuous, maybe I’m reading into it. Or maybe we were saying the same thing. The wonder of the moment of discovering something new. “The sound of surprise.” That’s what jazz is all about.

Lee Konitz was 70 when he recorded this. He told me that last month he had a reunion gig, at the Village Vanguard I think he said, with Haden and Mehldau, and with the addition of the magnificently modest drummer Paul Motion, four years younger than Lee. It was recorded by EMC and will be released soon. I can’t wait to add it to the 91 CDs on my shelf and hard disk. The ‘Alone Together’ trio with the perfect drummer. Lee Konitz breaking new ground, improvising the most fascinating, magical music I can imagine. I hope when I’m 83 I’ll be able to find my slippers. And maybe if I’m really fortunate, I’ll still be able to summon up the energy necessary to focus on this beautiful, moving music.

SoTW 134: Lee Konitz, ‘Duende’

SoTW 040: Lennie Tristano Quintet, ‘317 East 32nd’ (Live in Toronto 1952)

Thankyou for using my B/W photo of Lee Konitz, but would you be kind enough to put my name and copyright symbol under it. as proof of my ownership of the photo please see my web. terrycryer.com. Regards terry Cryer

Great to read this article mixed with interview parts. Knowing the great man since 1976 I buy each CD and collect all kind of private or radio tapes. The discography is still a work-in-progress – and hopefully will be the next 10 or more years.

Michael Frohne

I enjoyed this article. Good story about the guy who bumped into your chair. I also identified with not being able to answer a reasonable question on the spot.

A chance encounter aside, you know him intimately through the lifetime of musical gifts he gave, and was still giving, all the more precious when you savor them now.

Thank you for your generous gifts Mr. Konitz.

Great article and great music! Hope you’re all well down there in Beer Sheva.

Such an interesting article about a very interesting person!