June 5, 2011

The Fantasy

The Fantasy

Perhaps a person can be defined by his fantasies. There was a time when my wildest dream would have been Petula Clark asking me to come up to see her etchings. And there was a time when it was Phil Jackson asking me for advice on defensive strategy. And for quite a while (at an age I’ll refrain from admitting) I was seriously hoping to be reincarnated as Buddy Holly.

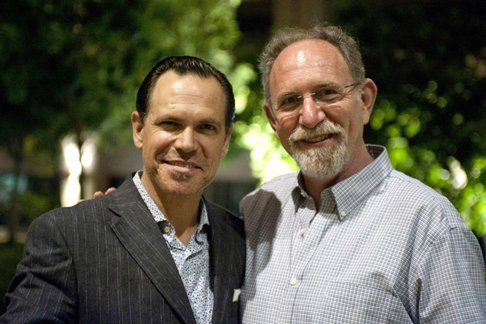

In recent years, my greatest fantasy would have been to spend the day talking music with my favorite singer in the world, Kurt Elling, while taking him to my favorite spot in the world, the underground tunnel that runs along the western wall of the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. Hey, guess what I did this week?

What do I mean when I say that he’s my favorite singer? Ever since I was a wee one, I’ve spent more of my mental energy listening to music than anything else. Maybe it hasn’t been a great career move, but it’s been my greatest passion. So when I say ‘my favorite singer’, I could modify that with the other couple of currently active vocalists I find really interesting, or with some greats from the past. But I’m not speaking off the cuff when I say that I think he’s the most interesting, accomplished vocalist around, and the best male jazz singer ever.

Kurt Elling has recorded nine albums since 1995. That I know all of them by heart is a given. That I’ve done my best to search out every guest spot that he’s ever recorded, every interview he’s given, is also understood from the git-go. That’s what I do with my favorite artists. And if he says that Mark Murphy, a relatively unknown beatnik singer, is his musical mentor, you can bet your booties I’ve digested as many of his 40 albums as I could find (only 14, and you can believe I’m embarrassed by that.)

Our wholly holey Holy Land has recently been greased–I’m sorry, I meant ‘graced’– with a host of stadium shows to which I’ve rushed to not buy tickets: McCartney, Leonard Cohen, Dylan, Paul Simon. I’m afraid to enter a musical Jurassic Park. I saw them when they were young and vital. Let legends lie. Give me active, young, vibrant artists.

So imagine my excitement when I heard that Kurt Elling was coming to Israel for two shows. In a really cool jazz club which happens to be on the ground floor of the building where I work in Tel Aviv. So I wrote Kurt’s management, asking for an interview. And I offered by the by, with my incalculable chutzpa, to take him out for an excursion, mentioning that it’s a very small country, and you can get pretty far in a half day’s outing.

How could he refuse, right? There were some last-minute email negotiations. Kurt and the band wanted to see Tel Aviv, where they were staying. Tel Aviv is a great, cool, vibrant city, the economic and cultural center of Israel. Nicknamed The Big Orange (as opposed to The Big Apple), it’s #3 on Lonely Planet’s Top Cities for 2011:

The total flipside of Jerusalem, a modern Sin City on the sea rather than an ancient Holy City on a hill. Hedonism is the one religion that unites its inhabitants. There are more bars than synagogues, God is a DJ and everyone’s body is a temple…a truly diverse 21st-century Mediterranean hub.

So of course I pushed to take them to Jerusalem.

The Plan

Because it’s the hub of the universe, and because it’s where where I first fell in love. First with the city, then with my wife. I pride myself on knowing it pretty well, and it’s a darn difficult city for natives to navigate, let alone tourists. Standing outside the hotel beside the rented van, I had 20 seconds to convince my favorite singer and his band to let me take them to The Old rather than to The New. “It’s the home of the three great monotheistic religions. Where heaven and earth meet. I want to take you to the place where God set his foot down on this planet.”

“Okay,” said Kurt. “Let’s go to Jerusalem.”

I’d just met the guys – Kurt, his pianist and collaborator Laurence Hobgood, guitarist John McLean, bassist Harish Raghavan, drummer Ulysses Owens, and road manager Bryan Farina. But with my own inimitable charm, I tried to convince them right from the start that they were being hijacked by a crackpot. “Know what we just did?” I asked as we settled into the 8-seat van and our driver set out for Jerusalem. The band members exchange glances. “We just re-enacted Psalm 122.” Raised eyebrows.

“I rejoiced when they said unto me, ‘Let us go unto the house of the Lord.’

Our feet are standing within thy gates, O Jerusalem.”

More glances. “That’s what just happened. I laid on you a ‘Hey, let’s go up to Jerusalem, and that in and of itself is cause for joy. Quick cut— in half an hour you’ll be standing in the Old City.”

Kurt’s getting just a little worried now about the lunatic in whose hands he’s placed his band and his daughter’s father. He asks me about myself, who I am, how I got to Israel, what I do in life. So I told him a bit about me, about how I was a graduate of Woodstock and a refugee from Kent State. I even sang him a little of an imbecilic autobiographical song I wrote called ‘Talking Jues Blews’. From behind his shades, he seemed to get that I’m not really dangerous, just over-enthusiastic.

Kurt Elling is first and foremost the epitome of Cool. Emotionologist Peter Stearns defines cool as “conveying an air of disengagement, of nonchalance…an emotional mantle sheltering the whole personality from embarrassing excess.” The term came into usage in the early 1950s to describe the Beatniks, a loosely affiliated group of artists from various fields, including William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Maynard G. Krebbs. These hipsters were goateed and sandaled and bereted, bongos in one hand, snapping fingers in the other as they recited poetry in a coffee shop to the strains of Le Jazz. Kurt Elling quotes these artists verbally and musically, he brings their aesthetic of bemused detachment to the stage, to his recordings, and to the van going up to Jerusalem. He’s controlled in the emotions he doesn’t express, and precise and measured in his speech, warm and generous and attentive in his demeanor. It’s onstage, in his music, where he gives free rein to an avalanche of passion. In the van, he’s all observer. Or maybe just jet-lagged.

Going Up to Jerusalem

“We’ve just crossed the coastal plain. This is Sha’ar Hagai, the beginning of the Judean Hills. Jerusalem sits up at the top. It’s about 45 miles from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. From the coast to the Dead Sea, the lowest place on earth, our eastern border with Jordan, is about 70 miles. That’s the whole width of the country. See those shells of old armored trucks? When the British pulled out of the area in 1948, Israel declared independence and six Arab armies immediately attacked. The population of Israel was 600,000, the Arab countries maybe 100 million. Jerusalem was under siege, and convoys were sent up into the hills with supplies. It was a suicide mission. These trucks are the memorial.

“I’m sorry, am I talking too much?” “No, no, please, go ahead.”

I love Jerusalem. I love its history, its crazy present, its uniqueness. I love that your accountant lives on the street where young David ran away from grouchy old King Saul. I love that you need to listen to the news report about US shuttle diplomacy to know when there are going to be traffic jams.

Singing Jazz

History is all good and fine, but in the van I have Kurt as a captive (if willing and congenial) partner for some music talk, an occasion I can’t resist.

JM: What were your initial influences as a singer?

KE: I grew up in church choirs. My father was the kapellmeister, so I learned whatever they put in front of us – Carmina Burana, The Messiah, The Requiem. I was fortunate enough to be involved with music in a deep way without thinking of it as a vocation or as a responsibility or anything I was forced to do.

JM: You didn’t have to practice. That’s one advantage to becoming a vocalist.

KE: Well, you can’t sing Carmina Burana by accident, but I got my basic training in a group setting. I’d listen to whatever pop music was on the radio, but I never really thought about it beyond “what does she want to hear when I pick her up in the Volkswagen?”

Then in college I was singing more Mozart, some Italians, Edvard Grieg. Then also some hipper stuff, Tony Bennett, Sinatra. On my family trips we’d listen to “Music of Your Life” stations, Perry Como, the Andrew Sisters, Bing Crosby. I always found that charming, so I developed a 2nd or 3rd hand nostalgia for that material, and at least a passing youthful acquaintance with a ‘swinging’ feeling. So that when cats were playing Brubeck, Herbie Hancock, or Grover Washington, Jr, it was kind of a disparate experience, but they all seemed to come from the same cloud.

Eventually I started taking Ella Fitzgerald more seriously. I wanted to learn in a deeper and more serious way what those recordings were all about. But then I got the chance to sit in as the “Stage Band” singer at Gustavus Adolphus College in Minnesota. That’s when jazz wasn’t yet a family word. Then we got some great professional guys from the Tonight Show coming through. A couple of them heard me and said, ‘Hey, man, you really got a sound. Are you thinking about doing this?’ ‘Well, it’s fun.’ ‘You should go down that road.’

JM: So you were informed at this point by imitating Ella?

KE: I already had issues of gender separation, key signature, we weren’t doing her charts. I hadn’t yet discovered Joe Williams or Pops [Louis Armstrong], let alone Jon Hendricks. Then someone said ‘Let’s go up to Minneapolis, check this singer Mark Murphy.’ It was my first time at a club like this, just thrilling, very emotional. I remember distinctly he did ‘Never Let Me Go’, at the end he goes back to the bridge [sings]. That just completely laid me out, really made me say ‘Now I want to check this out’.

We were driving straight up to Jerusalem, because I had to get the Kurt and the band back by mid-afternoon for a sound check.

We were driving straight up to Jerusalem, because I had to get the Kurt and the band back by mid-afternoon for a sound check.

But I’m going to take a conversational detour ahead here to talk about the poverty-stricken tradition of male jazz singers. In his book “The Jazz Singers,” prolific and perceptive critic Scott Yanow lists the 30 greatest jazz singers, only 11 of whom are men: Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Cab Calloway, Jimmy Rushing, Nat King Cole, Eddie Jefferson, Joe Williams, Mel Tormé, Jon Hendricks, Mark Murphy and Kurt Elling. I think he’s being overly generous to us members of the male persuasion, that vocally weaker sex, but I won’t quibble. I do think that the consensus opinion of jazz fans would agree with me in saying that except for Louis Armstrong and now Kurt Elling, there is no one on that list who rivals the great female jazz singers in artistic stature: Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington. Even in the second tier–fine, distinctive, admirable singers (Carmen McRae, Betty Carter, Anita O’Day, Nancy Wilson)–it’s all Sadie Hawkins.

Way back in the late 1920s Louis ‘Pops’ Armstrong virtually invented jazz, from swinging the tune to bending melodies to scat singing. He has remained a towering presence since. Modern jazz began in the late 1940s, and modern jazz singing with it. Jazz vocals in the 1950s and 1960s were mostly swinging renditions of standards, Pops’ collaborations with Ella Fitzgerald constituting the peak of that genre. Even the great female vocalists of the 1950s were not really adventurers. Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington and, to tell the truth, even Ella sang standards with impeccable taste and charm, but not one expanded the borders of music like pre-Bird Pops or Bird himself, or from the 1950s like a Miles or Monk or Mingus or Coltrane or Bill Evans, or later Wayne Shorter. In the 50 years since the Beatles hit the fans, there’s been only marginal jazz singing going on, although there has been somewhat of a renaissance in the past decade or two, some of it light and commercial, some of it quite challenging and serious and seriously groundbreaking (Luciana Souza, Esperanza Spalding, Kurt Elling).

Jerusalem

As we near the city of Jerusalem from the west, the conversation turns back to the non-musical. I explain about David and Solomon, 1000 BCE, the First Temple, on the same site where we’re headed. 931, the Northern and Southern Kingdoms split. 586, the Northern Kingdom is exiled, 10 tribes going lost. 536, stragglers return; 516, a small 2nd Temple is rebuilt. The Greeks, Hellenism, Maccabees, Romans. Herod rebuilds the 2nd Temple. Am I boring you guys? No, no, please, go ahead. Jesus is born, crucified. 70 AD the Temple is destroyed. Temple mount lies in waste till Moslems build 2 mosques in 700 AD.

We round a bend in the road, and our eyes rest upon Jerusalem, in the distance, nestled at the crest of the Judean Hills. The glory that is Jerusalem. The meeting place of heaven and earth. The center of the universe. The home of our God. The silence in the van reverberates.

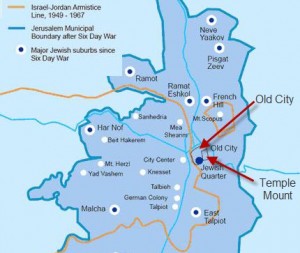

1880, I continue, Jews start to return to Jerusalem, neighborhoods are first built outside the walls of the old city. I show them all this on a map. 1948, the War of Independence. The Jewish Quarter of the Old City is captured and evacuated. A border between Jordan and Israel runs through the city, Jews in the western city, Arabs in the east, including the Old City. 1967, miraculous Israeli military victory, city reunited. Today, 600,000 Jews mostly in West Jerusalem; 150,000 Arabs in East Jerusalem.

The Old City

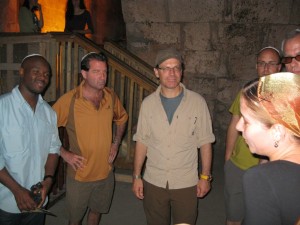

We enter the Old City of Jerusalem through the Jaffa Gate and walk down through the Arab market (the souq). Narrow, colorful alleyways, lined with tourist shops; less pungent, less frenetic than in years past, but cleaner, more sanitized, amiable.

We wend our way down the bazaar road, a mere 10 minute walk here in the city where history is so compacted, to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. According to some traditions, it contains the sites where Jesus was crucified, buried and resurrected.

When guiding tourists, I always try to clarify the distinctions between the strata of myth (Abraham and Isaac), legend (the Exodus), speculative history (Kings David and Solomon, First Temple) and verifiable history (Second Temple). But I was sorely unprepared to provide even a minimal background to the church. I later learn that the marble slab people were kissing that we were wondering about was the tomb where Jesus’s body was said to have been laid out.

We walk up through the Armenian Quarter, up over the roofs of the Jewish Quarter to a lookout over the Temple Mount. The entire Old City is about 1 kilometer square (1/3 mile), of which the Temple Mount occupies less than one quarter, in the southeast corner, about the size of 20 football fields. The Kotel, the Wailing Wall, is the exposed Western retaining wall of the Temple Mount. The walls of the Temple Mount originally rose some 10 storeys above ground level, but the Crusaders built a series of arcs to raise the level of the city to almost the height of the wall. Below was one giant underground garbage dump. The guys seem suitably awed. I’ve stopped asking if they’re bored.

Over the centuries, the Wailing Wall was just an alleyway where Jews prayed. During the British Mandate (1917-1948) Jews had access but limited permission to pray. Under Jordanian rule (1948-1967) it was enemy territory. After the Six Day War, a plaza was opened up to accommodate the many thousands of visitors. Down to The Wall. I try to get in a quick Mincha (afternoon prayer), but it’s a few minutes too early to start – there are minyans (prayer quorums) around the clock, but only within the proscribed times.

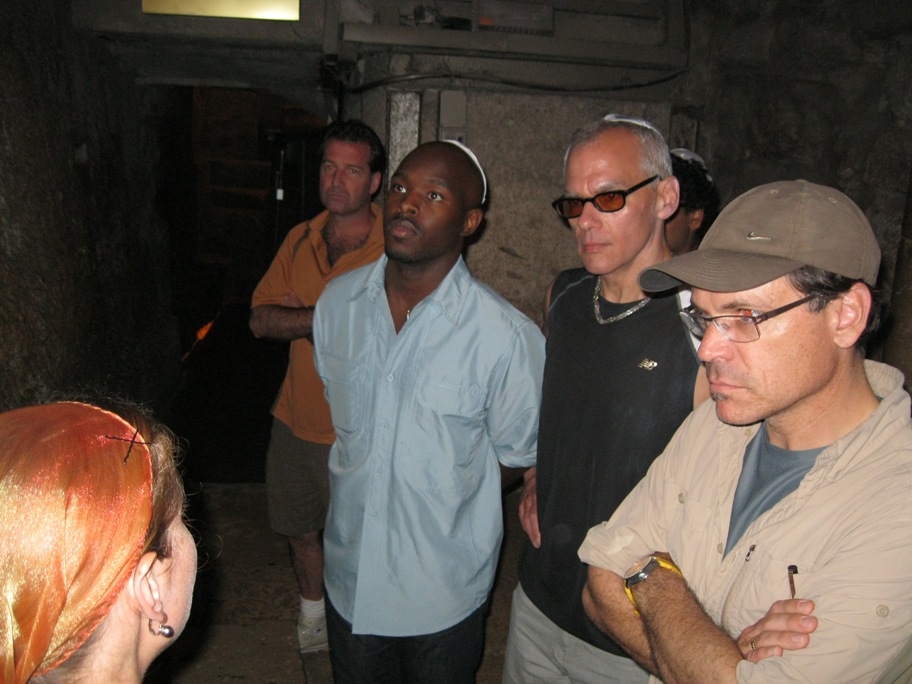

The Tunnel

Into the Western Wall Tunnel. The exposed Western Wall is 60 meters long; the tunnel continues for another 500, underground. We see the biggest stone, which is one of the heaviest objects ever lifted by pre-industrial humans, 13.6 meters long, weighing over 500 tons. On to Warren’s Gate, directly opposite the site of the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctuary of the Tabernacle and later the Temple in Jerusalem where the Ark of the Covenant was kept during the First Temple, which could be entered only by the High Priest on Yom Kippur. The Ark of the Covenant contained the Ten Commandments given by God to Moses and the Israelites at Mount Sinai.

For Jews and some branches of Christianity, it’s the spiritual epicenter of the universe, the focal point of prayer for 2000 years. Maimonides wrote in The Book of Temple Service in the 1100s: “When Solomon built the Temple, knowing that it was destined to be destroyed, he built underneath, in deep and winding tunnels, a place in which to hide the Ark. It was King Josiah who commanded the Ark be hidden in the place which Solomon had prepared.” Second Chronicles 35:3 might refer to Josiah removing the Ark of the Covenant from the Temple to the hiding place Solomon had made, before the Babylonian invasion: “And he said to the Levites who taught all Israel and who were holy to the Lord, ‘Put the holy ark in the house that Solomon the son of David, king of Israel, built.” We’re now standing underground, opposite that place. Indiana Jones, eat your heart out.

Our guide, Hadas, is a little slip of a young lady, with an Orthodox head covering and a beguiling British accent. The guys invite her to the show tomorrow night in Herzliya, and she sounds quite excited. You have to book these tours in advance, but we did it last minute (jazz musicians like to improvise). From the van I had spoken to the offices and played the VIP card to get them to run a special tour for us. Hadas just had time to watch a couple of Kurt Elling clips on the Web before meeting us. Admittedly, it’s not the Justin Bieber entourage, but she seems pretty charmed (and very charming).

Hadas points at the floor. “Do you see these stones? They’re from the original Roman street connecting the city to the Temple Mount. It’s a T-intersection, see?” The guys nod. “The traffic here would have been very heavy, a major thoroughfare. Anyone who went to the Temple would have walked here.” Our silence is audible. “The Romans built their courtroom right on the main street. They wanted to demonstrate to all the natives what happens when a Jew stirs up trouble.”

Out of the northern end of the Tunnel to the Via Dolorosa, the path that according to tradition Jesus walked, carrying his cross, on the way to his crucifixion. The precise locations of the Stations of the Cross cannot be identified scientifically, but there are hundreds of years of belief and tradition at play here, and we Jerusalemites have a lot of respect for that as well. Centuries of belief is also a historical fact.

Back to the Wall for the guys to catch their breath and me to catch my afternoon prayer. Past the archaeological park at the southern end of the Temple Mount (that’s what they’re leaving for next time) and out through the Dung Gate, where our driver is waiting.

I had hoped to take them on a quick jaunt to Mt. Scopus for a stunning view of the Temple Mount and, 100 meters eastwards looking down to the Dead Sea. But it was getting late, and we were all famished, and they had a sound check yet to perform down in Tel Aviv. Zip to a terrific, picturesque, restaurant for some Middle Eastern delicacies.

Jazz Singers

We gorge ourselves on 20 salads and authentic humus and skewered meats and music talk.

JM: There are so many great jazz instrumentalists. Saxophonists, trumpeters, pianists. The list of great jazz singers is so small.

KE: How many true singers are there, of any variety? In the 1950s, jazz was a music of the cognescenti, music of the cities. It’s hyper-intellectualized, urban folk music. It didn’t come up through the conservatory, it was one musician discovering something extraordinary, and teaching other musicians by example, other musicians learning by exposure, by their own personal identification, not by any set of academic course books. Is anyone getting kabob?

I understand that Kurt was saying here that singing jazz can only begin after the person has learned his trade, has done his years of homework paying his dues by studying the jazz vocal tradition. It cannot happen instinctively or intuitively, any more than one can sing Carmina Burana intuitively, or one can play a Beethoven violin sonata intuitively. And that’s just to get in the door. I still can’t figure out what he meant by that kabob remark, though.

KE: So at every level you have this winnowing process. You have these pop singers who are jazz touched, like Peggy Lee for example. Or Sinatra, for that matter, who was a very deeply swinging and innovative pop singer with a heavy jazz fabric. Or Tony Bennett. The real jazz singers are the ones who supercede their technical abilities. First and foremost, the greatest of all, Louis Armstrong. In the beginning, no one would listen to such a sound. But because of his musical mastery and the innovation of what he was doing, his voice became the conduit of innovation, not the other way around.

KE: So at every level you have this winnowing process. You have these pop singers who are jazz touched, like Peggy Lee for example. Or Sinatra, for that matter, who was a very deeply swinging and innovative pop singer with a heavy jazz fabric. Or Tony Bennett. The real jazz singers are the ones who supercede their technical abilities. First and foremost, the greatest of all, Louis Armstrong. In the beginning, no one would listen to such a sound. But because of his musical mastery and the innovation of what he was doing, his voice became the conduit of innovation, not the other way around.

Ella has struck me as a bookend, a natural singer who came to singing accidentally. Do you know the story? She was appearing at the Apollo in Harlem. She thought she was going to dance, but the girl before her did the same number, so she had to change. ‘What am I going to do? She’s dancing to my tune!’ She had to start from that musically uneducated perspective. She got her experience, her education under Chick Webb. So I see her as meeting Pops in the middle, which is why people love their records so. The perfectly effortless charm, the definitive swinging sounds coming from hyper-musical education and innovation with a less than stellar sound, meeting a perfect jazz sound that needed an education. That’s what I mean when I say there are very few vocal jazz innovators.

Is Kurt saying that neither Louis nor Ella provided a fully satisfactory package, that it was the amalgam of disparate skills and temperaments and backgrounds that galvanized the uniquely successful melding of the two? I don’t think so. Certainly regarding Louis, he holds him in the absolutely highest regard, and I don’t think Ella’s far behind.

Laurence Hobgood: You know, a vast number of singers are fascinated with the sound of their own voice. They may have a natural, pleasing-sounding voice, but the actual schematics of what music is doesn’t interest them very much. They don’t want to think about it a lot. To be a great jazz singer, you have to have some comprehension of the nature of the schematics of the music, whether it be book-learned or instinctive. But most singers don’t want to leave their comfort zone, which is feeling good singing within their ‘nice voice’.

Coming Down from Jerusalem

We’re leaving Jerusalem. I read to them a favorite passage of mine from S.Y. Agnon, Israel’s Nobel laureate for literature:

Places there are in Jerusalem which I know well; but when I happen upon one of them, it seems to me that I have never been there.

But then there are places where I have never been in my life, and when I come there, it seems to me that I am familiar with them and know them.

And because all the days, including the nights, frequently did I roam within the walls of Jerusalem – I never took the time to learn a trade. Worse than that! I neglected to learn Torah! And a Jew who isn’t occupied learning Torah, his heart reproves him and says: “What do you answer on Judgement Day, when you have neglected to occupy yourself with the Torah?” I answer it thus: “I occupied myself with Jerusalem,” and I am certain it will say to me: “You have done well!”

More Jazz Singers

Driving back down to Tel Aviv–as if showing the coolest singer on earth the neatest place on earth hasn’t been enough for one day–I get to start quizzing Kurt about other vocalists and musicians. I must have died and gone to heaven.

Driving back down to Tel Aviv–as if showing the coolest singer on earth the neatest place on earth hasn’t been enough for one day–I get to start quizzing Kurt about other vocalists and musicians. I must have died and gone to heaven.

JM: Bobby McFerrin?

KE: Bobby has taken a very broad latitude with the presentation of a vocal concert, a signature approach based on the fact that technically he’s omnicompetent. [These are quotes. This is really the way Kurt talks.] Where do you go to develop that? The stuff he did with Chick is incomparably emotional, a majesty of human accomplishment. But some of the stuff he does with choirs, with his own voicestra is ‘interesting’, but I don’t think it reaches that same ecstatic individualist, immediate collaborative moment of the stuff he does with Chick or even as a soloist. With choirs, I just don’t find it as interesting. That’s just not my bag. Far be it from me to say to someone of his caliber he should be doing this instead of this. But if I was going to put something on, I would put on Bobby and Chick going to it as a demonstrable, visceral archetypal, musical moment in human evolution. Because that’s what you want. You just bow down.

[I didn’t know that Corea/McFerrin album ‘Play’ all that well, but you can bet that the next day I went running to give it a couple of serious listens. Here’s their recording of ‘Spain‘. What can I tell you? Omnicompetent? Fo’ sure. Moving? Huh-un. Sorry. I’m enough of a singer to recognize that what Bobby McFerrin is doing is technically superhuman. I’m very impressed, but I’m not moved. Perhaps I’m too impressed to be moved.]

KE: Luciana Souza? She’s an extraordinary technician, her pitch is absolutely spot on all the time, her rhythmic sense, her ability to improvise over difficult changes, her writing abilities, just precision of her attack.

But then it becomes a different kind of question, one that Laurence and I have talked about a lot – does your vision follow your technical ability, or does one push one’s technical ability as far as one can to pursue a musical vision?

What if Monk had incredibly solid classical technique? There’s an upside and a downside. Fumble stumblefingers.

[I think that Luciana Souza has done some of the finest vocal jazz I’ve ever heard. Her technical prowess moves me beyond the level of craft, to the very quick of musical experience. But I’m here to hear Kurt.]

JM: What about Maria Schneider, and the way she uses Luciana Souza’s voice as an instrument in her orchestra?

KE: It’s good she has people she can call on to embody her vision.

Kurt and I are transmitting on different wavelengths here. From what I sense, and I could be very wrong, Maria Schneider is a very precious orchid, arousing in those who surround her feelings of tenderness and protectiveness. Kurt sounds more than sincere when he says this. I, on the other hand, don’t know Ms. Schneider personally. I know her music well, and admire it greatly. I find her employing Luciana Souza’s voice as a God-made instrument in her nebula of a brass orchestra to be amazingly innovative musically, jaw-dropping technically, and emotionally moving.

Kurt knows these people personally, and I sense that this colors his attitudes; but more importantly, he comes from the mindset of a working artist. And I of course come from the mindset of a music listener.

JM: I find Luciana Souza almost always a riveting artist. Except for her last couple of albums, which seem rather pandering to me, but she makes some music that is so great that—

KE: I don’t see Luciana doing any pandering. She’s way too smart for that. I think, like a lot of artists, she’s reminded of things from her past. And you know, she’s now in a collaborative relationship with her husband [Larry Klein], who has a very long pop history [producing Joni Mitchell at the end of her career, et al]. But you know, ‘pandering’, that assumes a lot. That means they’re actually consciously downgrading their abilities to win a less glorious reward. And I don’t think she has that in her to do that. She may be making choices that make it easier for more people to listen to. But ‘pandering’, that’s a pretty loaded word.

JM: But after she’s done such remarkable, fine, challenging jazz, to go make an album of pop songs done bossa nova style–

KE: Maybe she wanted to make something for her kid. Like lullabies. You know, there are any number of reasons why an artist chooses to go down a certain road that have little or nothing to do with saying, “Oh, well, this will really sell.” I just don’t think the process works like that. Not among jazz people. We all know we’re not going to make any money. You wake up in the morning knowing you’re [at best] going to break even. I just have a hard time suspecting somebody’s motives.

JM: I really didn’t mean to question her integrity, I’m just saying that those albums of hers seem significantly less inspired than–

KE: I don’t mean to be vibing, but ‘pandering’ is a pretty heavy word to lay out there.

Laurence: That just has to be a word writers like. The fact of the matter is that you got people out there that have been trying to do something for a long time, but they also need to have a life and pay the bills, and any time they try to do something that can be perceived as being just a little more commercial, everyone who’s supposedly a cognescenti who knows what’s better for the overall art, and they tend to jump on them, and like, you don’t know what their situation is. You don’t know why they’re—

JM: Mea culpa. Let me rephrase. I find her most recent albums less interesting—

KE: Less interesting, fair enough.

JM: She has albums that blow me away, that I’m astounded by every time I listen to them, that take my breath away. I love her music. I have infinite admiration for her as an artist—And I wish her wealth and happiness.

Consider me put in my place. There are creators of music and – well, I don’t like to call myself a music ‘critic’, because I try to find what’s right with music rather than what’s wrong with it. I like to call myself a music promulgator, but that’s maybe not a very snappy handle. Look, I understand. It’s easy for me to sit on my butt and say that such and such an album is lousy. Kurt and Laurence are looking at it from the side of the artist struggling to make a career out of music, both financially and creatively. I understand that one side of the equation is noble, god-like by definition, to be revered; the guy on the other side of the ≠ is a fly on the wall of the recording studio. (Hey, but Esperanza Spalding recently quoted a William Blake poem very empathetic to that fly.)

I’ve been thinking a lot about the interchange above. I clearly touched some exposed nerves. Are we to be reduced to only the blandest of opinions (‘I personally find that less interesting…’)? I don’t want to be cast in the role of the poisonous, pompous critic. On the other hand, I hope I have developed some tools for discerning some sense of the relative worth of musical endeavors in certain genres. Well, a lot more people will be buying and listening to “The Gate” and “Tide” than reading this article, which is as it should be. One endeavor is vital, the other is supernumerary.

JM: Esperanza Spalding?

KE: Beautiful stuff. She’s so smart.

JM: Do you like the music?

KE: I know it’s good, but it’s not the first thing I put on for enjoyment. I definitely respect anyone who takes a work of poetry like that for creating further works of art. It’s hard to make certain poets as singable as their poetry already is. To take it from the realm of the music that’s inherent to it without an actual literal melody, and to give it one that retains its singability.

[We talked about Found Poetry, where the poet takes a text written for a non-poetic purpose (such as a newspaper article) and by isolating words and thoughts using tools of versification invests in the words meanings beyond and above those originally intended. We somehow segued from that to the unity of some of Kurt’s albums. He sees “The Gate” as continuation of “Nightmoves“, hopefully more refined but without losing freshness.]

KE: “Nighmoves” had too many chefs. There was too much bloviating. But for “The Gate” we had Don Was in the room, and that brought a lot of confidence.

JM: Was that lacking in the past?

KE: You go in to make a record, it’s a very exposed experience. Can I really play live as well as I think I can? You get all these great people in the room, and you have to sing a new song. The money’s being spent, the clock is ticking. Every time I got pressured, Don took that out of even our peripheral vision. If any of the suits had a question, he would stick up for us. It doesn’t matter how much of a master you are, you want to have the right people in [the recording studio] supporting you.

JM: Why do you tour so much?

KE: Because I never see royalties. I wanted to be a touring musician, to see the world, to sing. The most profound experiences I’ve had have been in live settings, with audiences. I’m on the road 200 days a year. When you work hard at what you do, you get better. It’s what we do.

JM: What’s your vision? How do you see your career going? Do you see yourself reaching out to broader audiences?

KE: You have business partners that you’re working with. But not one of the selections, musicians, musical choices made for the new album was done to fool any one or pander [Okay, Kurt, I get it] or play less than we could play in order to gratify the bean counter.

That’s not the concern I was talking about that’s in a musician’s head when he goes into the studio. You want to play as well as you can, up to the level of the musicians in the room with you. The decisions about material and arrangements have been made before you go in. You’re exposed. Your heart is exposed. Everything you’ve worked for is exposed. Because every single note that you record can be soloed up and played a hundred times. You hear every single nuance. That’s very different from [the live experience of] ‘Oh, I hope you like it!’

There’s no temptation [for me to be really commercially-driven]. It’s too late for that. I’m a 43-year old jazz singer. I am that happily, by self-definition, and by the embrace of jazz people, if not universally then at least widely. And at the same time, I think that it’s my opportunity, challenge, a natural part of the artist’s life, to try to speak or sing to the largest audience possible. I’d like to go into a concert hall with these guys and sing for 10,000 people. I believe that what we do is going to make them feel better, speak to their better selves. It’s ennobling for us to play it; and without being Pontificating Sam, I think it’s ennobling for people to hear it. Here we are, five guys working on music together, supporting each other, giving all we can individually and as a group to create an occasion of beauty, an occasion of an opening of the heart, an occasion of music and time and space and harmony and rhythm. I think that’s a good thing, whether it’s us or five other guys doing it.

JM: I want to tell you what I, as a commercially insignificant blip on the record-buying screen, think. I think you’re the best male jazz singer ever, period. I don’t think there’s anyone else in your league. I’ve listened to a lot of Mark Murphy, and I have great respect for him as a singer, but I think you’re in a whole different league.

KE: Well, I’m here now–

This is Kurt being uncomfortable with the praise, trying to deflect it.

JM: Wait, I want to amplify on that. Not just a singer, as a musician. As you said, jazz vocalists haven’t traditionally been the most adventuresome of jazz musicians.

My background is rock more than jazz. I think in a sense it’s a more respectable role to be a rock singer. The range, the breadth of things that people are doing, creating a variety of types of creation. It’s a very broad umbrella. Early Randy Newman; the more obscure, quality James Taylor; Joni Mitchell; Robbie Robertson – really major-league artists. They’re writing their own material, creating a whole world. They’re not singing standards, backed by a quartet.

I think you’ve reached out to new areas, new fields that people haven’t explored. You’re an innovator. And I admire that innovation. Not just the quality of your singing, of performing the task you’ve set before yourself, but the task itself. You’ve set the ‘surprise’ bar very high. I like being surprised by your music, I like being challenged by your music.

KE: Thank you.

JM: I want to go back to Esperanza for a moment, to what we were talking about earlier, about jazz singers and innovation.

KE: I think she has a tremendous amount of potential to move the music forward. She has ambition, talent in lots of different directions. She’s just a baby, not yet 30. I was teaching out at Stanford, and invited Rufus Reid in to address my students. He made a point of talking about the necessity of longevity among jazz artists, the need for years of experience to refine and winnow and educate as a proving ground. ‘You take young Kurt here, he’s a fine young singer. He’s the teacher for you now. It’s easier for someone like Kurt to catch the ear for a year or two than it is to have a lifetime in jazz. It’s easy to get on the cover of Downbeat once. It’s very hard to get on it twice, or four times.’ Esperanza? I have nothing bad to say about her. Time will tell.

JM: I think she’s already done something of substance, found a way to amalgamate jazz and song. An innovation of substance.

KE: Here’s how I think of innovation as such. In any field in which a thought process is evolving – predator drones or jazz singing or orchestral music or spark plugs – there are going to be groups of people, or individual innovators, who show the possibilities. If society is like an amoeba, most of the people are just living their lives, then artists sometimes reaching waaaaay out. ‘Hey, can we go over there?’ – the antennae of the race. Sometimes when the possibilities show themselves attractively and clearly and draw a visceral response, then other artists will respond. Think of Charlie Parker. For a while there hasn’t been a [vocal] artist who has moved the ball down the field like Lambert, Hendricks & Ross did. Or in his own way Joe Williams, coalescing The Blues in the most sophisticated and urbane charts, all the things that were part of his métier, that couldn’t have happened without his particular set of gifts.

Jazz Singer Kurt

JM: I think you’re way too modest. I mean, sometimes I think you don’t even start to get how good you are.

[I’m trying to convey that the virtues he’s attributing to a Joe Williams are so minor in comparison to his own seriously innovative musicianship.]

KE: It’s not my job to get how good I am. I start thinking that, I stop practicing.

JM: Ok, you’re not that good.

KE: I’m a good all-round jazz singer. I’ve paid attention to that which has come before me. I respect it enough to try to understand what I can of it, how it can apply to this point in time. The physiological gifts and the technical obstacles I’ve overcome. But I don’t think that’s particular to me. I think that’s what a craftsperson is about.

JM: You are a fine craftsman, but also much more than that—

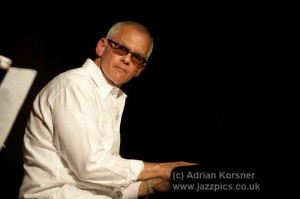

KE: And I have great collaborators. None of my stuff happens in a vacuum. What Laurence brings to the table is inherently–. It’s a whole different sound, a harmonic and rhythmic innovation. Having John on now, this rhythm section. It’s a collaborative sport. I admit that there aren’t that many singers that I need to listen to right now, but I can point to several who are moving the ball down the field, who have their heads in the right place, who are working as hard as they can to bring their visions to reality.

A word here about Laurence Hobgood. Kurt is always careful to give him credit as his long-time collaborator. I think that credit is fully deserved. Kurt’s ability to maintain such a high level of musicianship, of interesting, challenging, intelligent, surprising renditions seems indeed immeasurably indebted to Laurence’s ongoing contribution. His arrangements and accompaniment enable Kurt’s treatment of Standards to transcend the standard and help push him into realms of Adventureland.

JM: I associate you in my mind a lot with Brad Mehldau. The same age group. Incisively intelligent, sophisticated. Trained mind, thinking person, well-read, emotionally exposed, articulate. And a certain world view, an aesthetic. Musically, you’re both into deconstructing the song. What you do with ‘Norwegian Wood’ and what he does with ‘Martha, My Dear’, for example. The choice of source material, the attitude towards the source material. You both remind me of 11-year olds taking apart a radio to see what makes it work.

KE: I agree with you, Brad is a very smart artist, so dedicated. He really is engaged in the day-to-day discipline of creation that I find very humbling. He reaches out to a lot of different directions.

JM: Yet he seems like a pretty laid-back person.

KE: Conversationally. (Laughter) But you don’t produce all that stuff without being very restless, intense, focused – How about Fred Hersch?

JM: I don’t get him so much. He’s intelligent, sensitive. But compared to Brad Mehldau – where’s the vision, the voice?

KE: If we’re going to talk about people who are alive now, and are totally dedicated to craftsmanship, technique, and putting their lives on the line for the music, Fred’s among the people who come to mind for me. The level of self-discipline he has for continually creating new pieces. The composer in him is a very driven person. I think he has a very particular touch on the piano, a combination of clackety-clatter and a very dripping, limpid touch. I find that a very solid and immediate display of his intelligence, the heart that he’s got in him, the romance. His version of Billy Strayhorn’s ‘Star-Crossed Lovers’ is definitive. That recording owns that song.

We’re approaching Tel Aviv. The driver, apparently less than riveted by our conversation, has put on a Neil Young compilation CD.

JM: If you lost a bet and had to record a Dylan song, what one would you pick?

KE: Oh, I wouldn’t call that losing a bet. I just haven’t found the right Dylan song yet, because the chord changes tend to not be so interesting. I’m definitely interested, because in that world, I love what he’s doing. And certainly the expansive breadth of the directions he’s taken over the years is profound. And I really like the way he does interviews. I wouldn’t take that as a losing proposition at all. I would be hard pressed to find what tune that would be, though. Kate McGarry does a great job on ‘The Times They Are A-Changing’.

We’re going to have to wake up the guys soon.

JM: I hope you enjoyed the day. It was really wonderful for me to be able to share Jerusalem with you like this.

KE: It was great. Thank you so very much. And I’m glad you’re so encouraging about what we do. I’m glad you’re having a good time with it. We need to have people listening.

JM: I’d like to ask you a favor. There are a couple of young Israeli artists I admire a lot who aren’t signed to a recording contract. Project RnL, a pianist/singer duo who do incredible studio work, kind of progressive rock-informed. And Omri Mor, a jazz pianist with a big, loyal following here in Israel. I’ve made a CD of some of their stuff. I was wondering if I could impose on you to give it to the people at your label.

KE: Sure, no problem.

JM: I hope I’m not committing some breach of etiquette here. None of them are my nephews, I don’t have any vested interest in this. They’re just young artists that I’d like to see get a break.

KE: No, it’s my pleasure. I’ll be happy to. And I’ll listen to it, I’m always interested in hearing what’s going down.

We’re back where we started, at the hotel in Tel Aviv. The ghosts that walked the cobbled streets to the Temple are 2000 years past, back up in Jerusalem, but hopefully well-ensconced in the minds and souls of Kurt and the band. Our corporal selves, meanwhile, have returned to the present, to the city of sun and sin. There’s a quick rest to be rested and then their sound check, and – right, I almost forgot, there are a few hundred enthusiasts coming to see a show.

Thank yous and see you laters, and then I’m sitting in the club with a friend and some other acquaintances, still trying to process the day I’ve just had. Hard for me to grasp that after all this, I’m about to see Kurt and the guys perform.

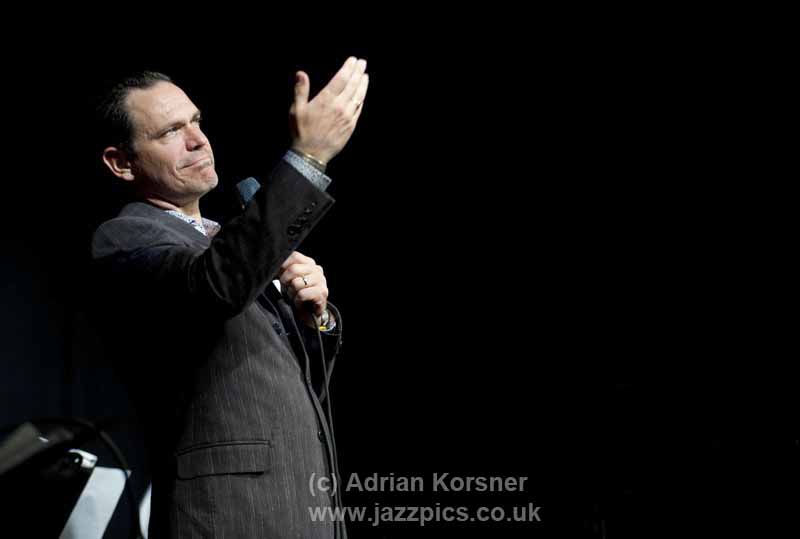

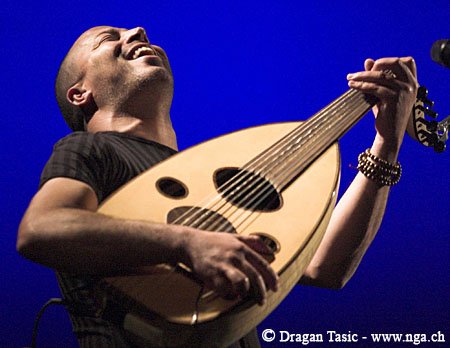

The Show

It was wonderful, spot-on every moment. They performed four songs from “The Gate” (covers of Joe Jackson’s ‘Stepping Out’, a an adaptation of bassist Marc Johnson’s lick over a solo by guitarist John Scofield on ‘Samurai Cowboy’, John Lennon’s ‘Norwegian Wood’, and Earth Wind & Fire’s ‘After the Love Has Gone’), the title track from “Dedicated to You“, ‘The Waking’ (words from poet Theodore Roethke, music co-written by Kurt) and ‘Luiza’ (written by Jobim, the inspiration for the name of Kurt’s five-year old daughter) from ‘Nightmoves‘, standards ‘Moonlight Serenade’ and ‘Nature Boy’ and Elling-penned ‘Higher Vibe’ from earlier albums. The biggest treat for me was Nancy Wilson’s ‘Save Your Love for Me’, not recorded by Kurt.

When I say that the show was ‘spot-on every moment’, I’m not just tossing out a phrase. Performing artists so often sing the song, or play the notes, or act the lines. Jazz, a genre self-defined as improvisatory, is supposed to transcend that pitfall by the very fact that it is created spontaneously, and therefore should avoid automatic recitations. “The sound of surprise.”

But in inferior performance art, the performer merely plays the notes or reads the lines rather than portraying a living version of what underlies them. I loved hearing John Barton, the legendary founder of the Royal Shakespeare Company, say that he can rarely hear Shakespearean actors, that it’s usually just ‘words, words, words’ that fly past him. What he (and I, and I think ultimately everyone) needs is to be totally engagée 100%, full-time. Play no note, speak no line, dance no step, until you understand why it has to be, what it means. Make every note, every word, every motion a cosmic necessity. That kind of intensity is crazy, and it’s why I admire off-the-wall artists such as Glenn Gould.

That intensity which empowers the performer to inform the score (or the script or the song) with living meaning, with an engendered reality, is a prerequisite for creative art. Even when he sings a standard, Kurt Elling has that very rare intensity, commitment, engagement in his material.

Back on Earth

Kurt, I admire your inherent modesty, and your adherence to humility before the fine artists from whom you’ve learned. But lest there be any misunderstanding – this is Next Generation singing, vocality for the 21st century. It’s what you called an “ecstatic individualist, immediate collaborative moment.”

So thank you for the day. I hope you enjoyed visiting Jerusalem as much as I enjoyed taking you there. Thank you for the great show. And thank you for all your wonderful music, and the many hours of pleasure it bestows on me.

For an in-depth comparison of Kurt’s achievement versus Mark’s, you’re cordially invited to check out Song of The Week 101: Kurt Elling, “Li’l Darlin'”.

You can find lots more great reading material about Kurt Elling at his official Website.

Great sotw!

A shame you didn’t go into more detail… this brief synopsis just isn’t enough!

Excellent piece, Jeff–really a great read, together with Li’l Darling post.

I must say that your blog has been instrumental into introducing me to several marvelous musicians that I might not otherwise have encountered, their being outside of the genres I tend towards. Kurt Elling is one.

Regarding Mcferrin: Sometime in the early 1980’s, while I was in the IDF, I went to see an open-air concert in the Sultan’s Pool in Jerusalem. I believe the main event was Dave Brubeck…but there was an opening act. I didn’t recognize the name. Now, you know the deal: Israelis at an open air concert. Loud, talking, jostling for a place on the grass…this was years before the bleachers were installed. I’d climbed up to a ledge on the side of the valley.

So, loud. And then–this VOICE. The opening note to Summertime cuts through the noise–not because of its volume. That note was not loud…it held an incredibly compelling, ethereal quality that, by its end, had brought total silence to the audience.

No mean feat, you’ll agree.

His entire performance was amazing. I must say that I may well find his music moving today because of that first, moving introduction.

AND BTW–it was lovely of you to give CDs of RnL and Omri Mor to Mr. Elling. I certainly hope they are heard by the right people. We grow some fine musicians, here in the Holy Land 🙂

Thank ye, ma’am, muchly. As JT says, “That’s why I’m here.”

Great pics of Kurt performing

Thanks so much for all this. I’ve only just found you, and it’s great to read what you have to say. I’m a great fan of Kurt Elling too, and have followed some of the same recordings as you. (How about ‘A New Body and Soul’?)

I’ve subscribed to SoTW!

Thanks again.

thanks Jeff- I too consider him the best in the biz and one of my all-time favs. in fact, I’ve told Laurence before I consider them the Lennon/McCartney of Jazz composers…they are a head above the rest. This man’s voice and music (and btw- not nearly enough credit is ever given to Hobgood), inspires and touches my soul in a way that only few others do for me. Great article and I’m so glad I found this website.

Thanks so very much.

Kurt elling for the Japanese fans, great coverage and LIVE sound very nice. I want you to come to Japan next.

Again, thank you.

Now to go to Jerusalem with my wife.

Kurt Elling,

He is Jazz!

Up and say enough is the best.

I sing his songs, too painful, sad, angry myself, feel miserable. But it is more fun.

I want to come to Japan soon.

Kurt Elling,

He is Jazz !

I want to come to Japan soon.

hi jeff

your articulate enthusiasm is contagious.i am a big fan too.inspite of tireless effords to prosilytize everyone around me i didn’t meet with any success so far ,maybe i should get divorced or look for a new circle of friends,or ….. look for fellow admires on the internet to not feel so forlorn.thank you very much.i read this article with great interest,all the questions you ask were (if i had your chuzpe) questions i would have like to ask him too.probably also because of the somewhat informal way of you arrangement with him it read different then other interviews with him i read.i especially enjoyed your questioning him about other musicians,singers in particular.great!

Hi Jeff,

Mark Murphy is hardly an “unknown beatnik singer,” but he is a living legend, a giant of this music. Without him, there would have been no Kurt Elling, jazz singer, a fact Kurt readily acknowledges.

Best, Jay