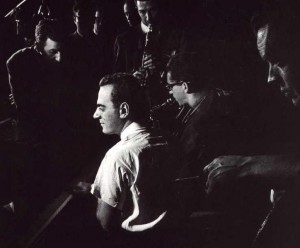

Ladies and gentlemen, meet Lennie Tristano. I’m probably not going too far out on a limb if I assume that very few of you have ever heard of him.

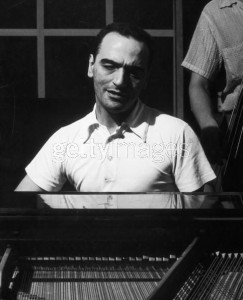

Chicago pianist, blind from birth, 1919-1978. Moved to NYC 1946, at the height of the bebop’s popularity. Made a few recordings. Made friends and enemies with his pioneering experiments in overdubbing and tape manipulation. Recorded the very first experiments in free jazz (turn on tape, pay attention, start playing without the safety net of a song, and good luck). He was just a little popular in the early 50s. From 1951 he concentrated on teaching.

Chicago pianist, blind from birth, 1919-1978. Moved to NYC 1946, at the height of the bebop’s popularity. Made a few recordings. Made friends and enemies with his pioneering experiments in overdubbing and tape manipulation. Recorded the very first experiments in free jazz (turn on tape, pay attention, start playing without the safety net of a song, and good luck). He was just a little popular in the early 50s. From 1951 he concentrated on teaching.

He was also an obstreperous, obnoxious opinionated bastard, a dictator of a teacher who inspired both cultish loyalty and great resentment among his former students.

Bebop was Charlie Parker, Bird–frenetic, fast, adventurous, impassioned. He would stagger onstage at gigs, hours late if he appeared at all, drunk and high and dissolute, grab the nearest sax and blow his heart out.

Lennie Tristano was the antithesis to Bird. He demanded rigorous practice, intense concentration and discipline. He insisted that the musician take responsibility for every note he played.

Tristano forced his rhythm section to serve as a metronome, providing a regular, mechanical pulse. Remarkably, such creative musicians as bassist Charles Mingus and drummer Max Roach were Tristano supporters. Because on top of that pulse, he would reorganize the bar, displace the metric system, create a disjointed and constantly surprising world. You can count tick-tick-tick without problems, but try one-two-three-four and at some point you’ll find yourself in a world of temporal relativity. It’s a shame Tristano never invited Einstein to sit in on violin. He would have felt very much at home, I think. Well, Aaron Copland was a big fan, if that counts.

Tristano forced his rhythm section to serve as a metronome, providing a regular, mechanical pulse. Remarkably, such creative musicians as bassist Charles Mingus and drummer Max Roach were Tristano supporters. Because on top of that pulse, he would reorganize the bar, displace the metric system, create a disjointed and constantly surprising world. You can count tick-tick-tick without problems, but try one-two-three-four and at some point you’ll find yourself in a world of temporal relativity. It’s a shame Tristano never invited Einstein to sit in on violin. He would have felt very much at home, I think. Well, Aaron Copland was a big fan, if that counts.

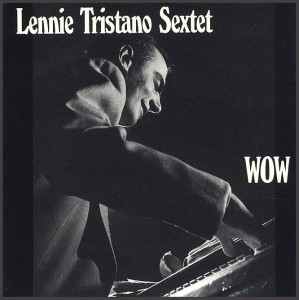

The cut we’re presenting this week is called ‘Wow’, from an obscure recording of the same name, from an undocumented date live in New York in 1950. For those of you who can’t take the excitement, here’s a tamer version of the same song in a studio recording from the same period.

Tristano often took popular songs and transmogrified them beyond recognition, mostly for copyright reasons (that way the musicians were also paid as composers). ‘Wow’ is based on the chord progression of ‘You Can Depend on Me,’ an old standard. Here’s a version by Count Basie, and here’s one by beboppers Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt.

Eunmi Shim, in her book on Tristano, has this to say about ‘Wow’: “This intricate melody is linearly constructed and thematically developed through polyrythmic figures and varied phrase lengths, which undermine the modular phrase structure of its model.” Thanks, Eunmi. Couldn’t have said that better myself.

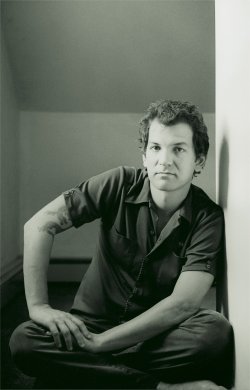

The group here is Tristano’s core sextet, with Billy Bauer on guitar and one-track tape recorder, and an unknown bassist and drummer. The saxophonists here are his regulars, his prize students, two of my very favorite musicians: Lee Konitz on alto sax, Warne Marsh on tenor sax. Marsh remained a loyal devotee of Tristano throughout a commercially mediocre but critically acclaimed career up to 1987, when he died on stage playing ‘Out of Nowhere’. Lee Konitz left the Tristano circle in 1953. He maintained his admiration for his teacher but felt he needed to try new, less stringent waters, although he continued to play and record with Tristano and Marsh intermittently for many years. He is still going incredibly strong at 82, having released close to 40 CDs in the last decade! And I can testify, each one is a new, ballsy experiment. No resting on the laurels for Lee.

The group here is Tristano’s core sextet, with Billy Bauer on guitar and one-track tape recorder, and an unknown bassist and drummer. The saxophonists here are his regulars, his prize students, two of my very favorite musicians: Lee Konitz on alto sax, Warne Marsh on tenor sax. Marsh remained a loyal devotee of Tristano throughout a commercially mediocre but critically acclaimed career up to 1987, when he died on stage playing ‘Out of Nowhere’. Lee Konitz left the Tristano circle in 1953. He maintained his admiration for his teacher but felt he needed to try new, less stringent waters, although he continued to play and record with Tristano and Marsh intermittently for many years. He is still going incredibly strong at 82, having released close to 40 CDs in the last decade! And I can testify, each one is a new, ballsy experiment. No resting on the laurels for Lee.

If you’re interested, here’s the Lennie Tristano Quintet playing Subconscious-Lee in a pretty rare clip from a 1964 Sunday-morning Christian-content television show exploring the subject of inspiration in jazz. Cool!

So what are we going to hear here in ‘Wow’? It starts with a group statement of the theme. At 0:45 Warne Marsh plays a solo, which at 2:00 he passes to Bauer in mid-phrase. At 3:15 Konitz plays his lovely, oblique, solo. ‘Like a long-legged fly upon the stream’, in W.B. Yeats’ words. And at 4:30 Tristano takes the reins. Ah, the beauty of form. At 7:00 the saxes and guitar return, passing the melody lightly between themselves. At 7:43 a group restatement of the theme. And then, miracle of miracles, listen to the phrase at 8:03 (well, a phrase in Tristano’s language can go on for many, many bars). All 4 lead instruments playing that wild, slippery equation, the alto a third up from the tenor at a speed that defies comprehension, as if that’s the sort of thing that humans are actually capable of doing.

And it all makes sense.

Over the last decade, I’ve spent an awful lot of hours listening to Lennie Tristano and his disciples. I often ask myself why. What is the pleasure in these cool, mathematical abstractions? The best answer is a phrase I wish I’d coined:

Ice also burns.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

SoTW 40: Lennie Tristano Quintet, ‘317 East 32nd’ (Live in Toronto 1952)

Beautiful music! Interesting article!

I love Tristano and your bolg – as ever- is both welcome and insightful.

..and sorry about the spelling blip (bolg!!). I’ve had sort of disagreements with mates who can’t get Lennie’s structured approach. But for me that’s the appeal. Love the Einstein reference as well!!

There’s a whole lot of music theory being discussed, and I really appreciate it. Truth be told, my simple ear can’t quite comprehend it all, I just know that “Wow” is utterly cool and makes me feel like a chick sitting in a coffee house in a beret, holding a long cigarette between her fingers.

“Because on top of that pulse, he would reorganize the bar, displace the metric system, create a disjointed and constantly surprising world.’

there you go, and welcome to the world of the late music of Stefan Wolpe. go listen to his Chamber Piece No. 1 for 14 Instruments (1964.) It’s entirely in 4/4, with the exception of a bar or two approaching a sort of cadence near the home stretch of the piece, if memory serves.

Wolpe (19902-72), died in NYC. where he had lived since emigrating from Germany via Palestine in 1938. I like to think he and Tristano crossed paths downtown at some point.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odm_mM6pz-A

this recording is not from Crosscurrents. could you share album info?

Thanks for the Wolpe tip. Shall definitely check him out.

I always find Tristano’s discography a slippery slope, but I know that cut from here:

https://www.allmusic.com/album/wow-mw0000092923