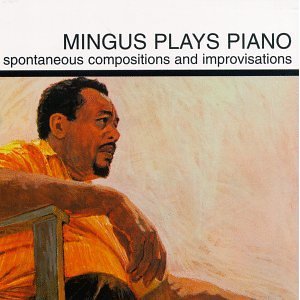

Charles Mingus, ‘Myself When I am Real’, from “Mingus Plays Piano”

Charles Mingus, ‘Adagio Ma Non Troppo’, from “Let My Children Hear Music”

I came to jazz late in life, by a rather circuitous route. I’d been immersed in rock & roll since I was knee high to a grasshopper, and grew up with rock. I was 15 when ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ hit the radio, and lived within that music for the rest of the decade (quite literally, actually — I once saw a Grateful Dead concert from inside a loudspeaker; what’s that you say, Granny?).

I came to jazz late in life, by a rather circuitous route. I’d been immersed in rock & roll since I was knee high to a grasshopper, and grew up with rock. I was 15 when ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ hit the radio, and lived within that music for the rest of the decade (quite literally, actually — I once saw a Grateful Dead concert from inside a loudspeaker; what’s that you say, Granny?).

Thirty years later I went through a mid-life crisis. As always, I took care to DJ my life. I stopped listening to rock cold turkey, nourishing my bruised soul with the Bach solo keyboard oeuvre (see SoTW 5, Glenn Gould, Toccata in Cm) for two years non-stop, attempting to impose order on an otherwise chaotic world. Then I segued to the Preludes & Fugues of Dimitri Shostakovitch (see SoTW 84, Dmitri Shostakovich, Prelude & Fugue No 16 in B-flat Minor), an homage to Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier”. And then, somehow, I tripped over Charles Mingus’s “Let My Children Hear Music,” an orchestral album he made in 1972.

To this day I associate Shostakovitch and Mingus in my mind. They’re both highly intellectual, willful, charismatic composers; often severe, harsh, brutally truthful; with not a little sweetness and romanticism in the mix. They’re both masters of melody who more often choose non-melodic, frequently atonal modes of expression. Often with both I find the accessible, the whistleable, bobbing and peeking through the dense forests of magnificent, grandiose, overwhelming angry constructs.

To this day I associate Shostakovitch and Mingus in my mind. They’re both highly intellectual, willful, charismatic composers; often severe, harsh, brutally truthful; with not a little sweetness and romanticism in the mix. They’re both masters of melody who more often choose non-melodic, frequently atonal modes of expression. Often with both I find the accessible, the whistleable, bobbing and peeking through the dense forests of magnificent, grandiose, overwhelming angry constructs.

So I started to learn jazz. I put nose to grindstone, downloaded a dozen lists of Essential Jazz Albums, sold my designer rock LP collection to a Dutch dealer and used the money to buy The 50 Greatest Jazz CDs. And no looking back.

I’d known an odd smattering of jazz beforehand–”Kind of Blue“, Vince Guaraldi’s “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” album, the inescapable Getz/Gilberto, even the original soundtrack of “Orpheu Negro”. But somehow I think of “Let My Children hear Music” as the first jazz album I encountered, fell in love with, and sort of understood on its own terms, going to it as A Jazz Album, meeting it there on its home ground and dealing with it as such.

It’s a strange place to start jazz. It’s an orchestral album, more or less, rich arrangements ranging from a medium-sized combo to big band to full orchestra. It’s almost symphonic in conception, large-scale pieces running around ten minutes. The music is grandiose, inspired, inspiring, large-canvas.

It’s a strange place to start jazz. It’s an orchestral album, more or less, rich arrangements ranging from a medium-sized combo to big band to full orchestra. It’s almost symphonic in conception, large-scale pieces running around ten minutes. The music is grandiose, inspired, inspiring, large-canvas.

Charles Mingus (1922-1979) was a linebacker-sized bandleader, composer and bassist. He was brilliant and impossible and left a legacy of music employing an exceptionally wide range of styles, as accomplished as it is varied. Here’s the avant garde Charlie (with Eric Dolpy). Here’s the cuddly one (‘Self-Portrait in Three Colors from “Ah-Hum”). And here’s one of the first SoTWs I ever wrote, about his composition ‘Remember Rockefeller at Attica’, one of my very favorite Opening Cuts.

He had a lot of fun with the names of his compositions. “Let My Children Hear Music” includes ‘The Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife are Some Jazz Ass Slippers’; “Mingus Plays Piano” includes ‘Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blues.’ Other notables include ‘All the Things You Could Be By Now if Sigmund Freud’s Wife was your Mother’, ‘If Charlie Parker Were a Gunslinger, There’d be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats,’ and ‘Pithecanthropus Erectus’. He often gave the same composition different titles.

He had a lot of fun with the names of his compositions. “Let My Children Hear Music” includes ‘The Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife are Some Jazz Ass Slippers’; “Mingus Plays Piano” includes ‘Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blues.’ Other notables include ‘All the Things You Could Be By Now if Sigmund Freud’s Wife was your Mother’, ‘If Charlie Parker Were a Gunslinger, There’d be a Whole Lot of Dead Copycats,’ and ‘Pithecanthropus Erectus’. He often gave the same composition different titles.

On the one hand, he came into the studio with a very firm conception of what he wanted. On the other, he demanded the most creative skills from his musicians. Mingus was known to refuse to write out charts for his recording musicians, as was the practice of the time. He would teach them the fundamentals of the composition aurally, and then demand that they improvise the rest. He demanded involvement, total musical commitment. He once beat up one of his band members on stage, for not doing well enough during a performance.

The origins of the compositions on “Let My Children Hear Music” are obscure. I just re-read the history of the album as described in the definitive autobiography “Mingus” by Brian Priestley, and it’s simply incomprehensible. And here are Charlie’s original liner notes, extensive, brilliant, also incomprehensible.

The origins of the compositions on “Let My Children Hear Music” are obscure. I just re-read the history of the album as described in the definitive autobiography “Mingus” by Brian Priestley, and it’s simply incomprehensible. And here are Charlie’s original liner notes, extensive, brilliant, also incomprehensible.

So let’s just stick to the few bare facts that are pretty clear and reliable here. From the mid-50s to the mid-60s, Mingus recorded several albums a year, mostly in a 5- or 6- piece setting, but not rarely employing other voicings. The music had a vast range, from the obstreperous, strident and experimental to the sweet and memorable. He drew on blues and Ellington and poetry and Mexico and everywhere else under the sun. He confined himself to playing the bass, kept the same drummer (Danny Richmond), but switched other accompanying musicians frequently, due to no small extent to the fact that he was an obnoxious bully on the bandstand, virtually impossible to work with.

Following a personal and physical crisis from the mid-60s to the early 70s, Mingus hardly recorded or performed. His creative powers returned for a short while, but then he contracted Lou Gehrig’s disease and died in 1979 at the age of 57.

In 1963, he recorded a solo piano album. Mingus of course played a little piano, probably doing most of his composing there. But he wasn’t considered much of a player per se. The album, “Mingus Plays Piano”, is one of my favorites of any genre. It’s heartbreakingly personal, intimate, candid, including both covers of standards (‘I Can’t Get Started’, ‘Body and Soul’), Mingus originals (the classic ‘Orange was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blues’), and one remarkable improvisation, ‘Myself When I am Real.’ This is how Mingus describes it in the liner notes:

Now, on this record there is a tune which is an improvised solo and which I am very proud of. I am proud because to me it has the expression of what I feel, and it shows changes in tempo and changes in mode, yet the variations on the theme still fit into one composition. I would say the composition is on the whole as structured as a written piece of music. For the six or seven minutes it was played (originally on piano), the solo was within the category of one feeling, or rather, several feelings expressed as one.

Please, listen to it. Improvised, he says. Incroyable. Such rare beauty. Such art. How could he not be proud of it?

Then this is where the story gets weird. Someone, maybe Hub Miller, transcribed it. Then maybe someone named Alan Raph orchestrated and conducted it. Then maybe Mingus sat in the corner and watched a whole orchestra perform it for “Let My Children Hear Music”, under the production and supervision of Teo Macero. I even read one account that said that the latter was actually recorded over the original, but I hear no piano in the mix.

The resulting track is called ‘Adagio Ma Non Troppo’. ‘Adagio’ means ‘slow’ in musical terminology. ‘Ma Non Troppo’ means ‘but not too strictly’. Listen to it. Is it not moving? Was it not worth venturing out of the cozy mindless comfort of rock music for this?

I once saw a gig by the Charles Mingus Dynasty, a 7-piece group dedicated to performing his music, not slavishly reproducing it, but admirable going with the spirit of his voice. Charles’ widow Sue was in the audience. I introduced myself as a long-time fan. She thanked me. It was somehow unsatisfying. So let’s escalate it a level–thanks, Charles. What a great experience, listening to the bare sketch and then listening to the fully-fleshed version. Like holding the miracle of a new-born baby and then skipping to the next track, the kid all grown up holding a stunning work of art he’s just created. All the potential, all the realization. How wondrous can be the works of man.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

Great choice Jeff, though I have to admit that Mingus always intimidated me. Maybe this will be the breakthrough….

Thanks! In the realm of Jazz, Mingus has always been the top of the top for me – complex compositions and arrangements, strong playing, and above all, a strong undercurrent of Blues, Gospel, and Soul in all his music.

Thanks for this article, very good read, one of the few webs that gives the praise it deserves to Mingus essence. It’s my favorite musical artist from the 20th century.

Myself When Im Real is a improv/composition from the heart, it’s so honest, so beautiful, it’s his spirit in a single piece, when you can explain yourself in form of music like that you enter the highest form of art like few composers achieve…

Though my favorite album is “The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady” (also a big band album) His full orchestra album is my 2nd fav.

IMO Mingus was probably the only jazz real composer who could be compared to classical composers of the century. Just so creative, very talented in arranging, high musical comprehension, admirer of classical music and a wild spirit, his music is a force of nature.

Keep the good work!

I was looking for a cool track to play during a yoga sequence and came upon Myself When I Am Real. I made this the pidgin pose track which in yoga is a very emotionally reflective and releasing posture. I could tell without knowing anything about this track that this was Mingus’ own reflection on who he was – if only for that moment creating that song, but the depth is also undeniably telling a story about his foundation, his struggle, and his self-realized potential. Thanks for sharing the backstory!

Love your take! Thanks.

This was great, I have been researching for a while now, and I think this has helped. Have you ever come across Health Herbs Clinic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis HERBAL FORMULA (just google it). It is a smashing one of a kind product for reversing ALS completely. Ive heard some decent things about it and my buddy got amazing success with it.