Paul Robeson, ‘Go Down, Moses’

Well, Passover is upon us, and She Who Must Be Obeyed is busy polishing the wine cups and sterilizing the corkscrew. She’s given me a few minutes off from helping for good behavior (actually, for gross incompetence), so I’ll try to squeeze in a few appropriate words on the music of the season.

I can’t complain about the spring cleaning tasks. Well, I can, but I shouldn’t. Not when I think back to my forefathers, and the travails they underwent at the hands of Ol’ Pharoah. I know just how bad they had it, thanks to the moving description of those hardships by our soul brethren, the African-Americans who created the spirituals. Slaves in the South were forced to go to church and sit on benches, to quell any ecstatic impulses they might still have from their native African worship. Shackled spiritually as well as physically, they were resourceful enough to create a lasting body of music which jumbled up their old religion and music with the new ones their European masters were imposing on them, resulting in songs of faith which expressed all the suffering and indignity they were living, albeit couched in thinly veiled Bible stories.

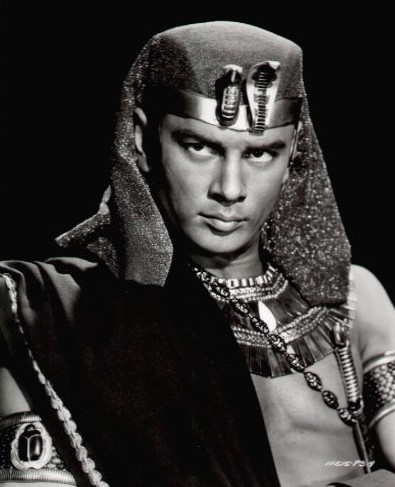

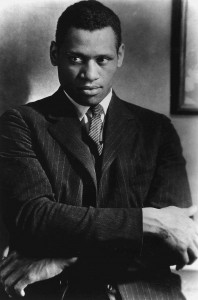

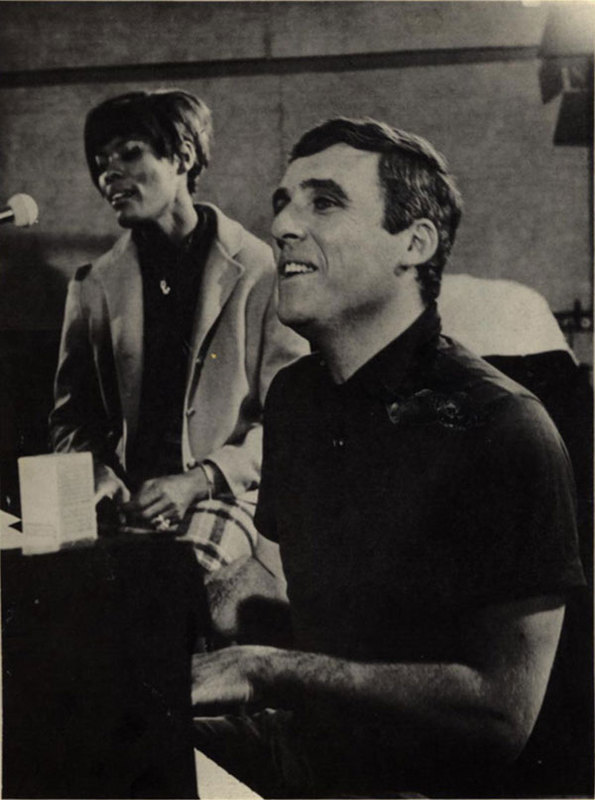

Paul Robeson’s (1898-1976) is a remarkable story by any standards. His mother died when he was six, so he was raised by his father, an escaped slave who graduated college and served as minister of a Presbytarian church in Princeton, NJ until his politics got him fired. Robeson was the only black at Rutgers University, class valedictorian, and All-American football player. He put himself through Columbia law school by playing professional football and basketball. In his spare time, he starred in a play which played in New York and London.

He married Eslanda Cardozo Goode, a descendent of slaves and Sephardic Jews, a graduate of Columbia in chemistry. She passed on medical school to manage her husband’s business affairs. His other affairs she also learned to manage to live with, as they practiced an open marriage until her death in 1965.

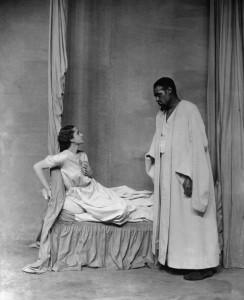

After Robeson quit his NY law firm (because a secretary refused to take dictation from a black man), his interests turned to the stage. He was the first to bring spirituals to the concert stage, starred in a play by Eugene O’Neil and was cast to star in the movie version of Porgy and Bess (till he was dropped for arguing politics with the director). In 1930 he went to London to play Othello (because no American stage company would employ him–although later, from 1943-45, his Othello became the longest running Shakespeare production on Broadway to this day).

He also sang ‘Ol’ Man River‘ in the immensely popular Broadway musical and movie “Showboat”. It was written for him by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein (neither of whom were particularly black, but both of whom had slavery hard-wired in their cultural heritage). The song has become one of the definitive expressions of black suffering. Robeson later changed the lyrics to transform the song from a lament to an expression of defiance.

In the 1930s and 1940s he was a star, performing spirituals in concerts throughout the world. But he also became radicalized politically, actively supported causes as wide-ranging as labor unions, the fight of the Republicans against Franco, the plight of Jewish refugees from Hitler, Welsh coal miners, the independence of African countries from colonial rule, the civil rights of blacks in the US, the integration of blacks into professional sports, (gee, just typing the list is getting me tired), and, most notably, empathy with the Soviet Union. Testifying before HUAC regarding his pro-Stalinist proclamations, he said: “You are responsible, and your forebears, for sixty million to one hundred million black people dying in the slave ships and on the plantations, and don’t ask me about [Stalin], please.”

His passport was revoked for a number of years, and when it was restored in 1958 he traveled to Moscow to accept the Stalin Peace Prize. His later years included self-imposed exile to the Soviet Union, mental and physical health problems caused at least in part by constant surveillance. He attempted suicide, was probably slipped LSD by the KGB, underwent shock treatment in East Germany, was hounded by the FBI (he reportedly owns the largest file in their archives), and finally retired to his sister’s house in Philadelphia. Whew. And that’s leaving out a lot.

But we stray. The Wife is calling me back into the kitchen. So let’s put on the soundtrack of our festival of freedom, and get back to work. I’m not quite clear how Yoshke slipped into the last line of the song. If you sing it at the table seder night, I suggest you improvise some other lyrics.

When Israel was in Egypt’s land (let my people go)

Oppressed so hard they could not stand. Go down, Moses, way down in Egypt’s land;

Tell old Pharaoh to let my people go.

The Lord told Moses what to do,

To lead the children of Israel through.

They journeyed on at his command,

And came at length to Canaan’s land.

Oh, let us all from bondage flee,

And let us all in Christ be free.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also like:

039: Blind Willie Johnson, ‘Mother’s Children Have a Hard Time’

058: Dave Frishberg, ‘Van Lingle Mungo’

102: Netanela, ‘Shir HaYona’ (Matti Caspi)

Have a great Pesach, Jeff.

Great post, Jeff.

Robeson was an awesome man, in the true sense of awe-inspiring.

Happy Pesach!

Cara Bereck Levy

Great Passover post

“Upon returning to the United States, he denied any persecution of Jews and other political prisoners, stating that he “met Jewish people all over the place… I heard no word about it.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_views_of_Paul_Robeson#Silence_on_Stalin

As far as I know, Paul Robeson never appeared in Porgy and Bess, although by one account he “briefly played the role of Crown in the 1927 production of the [non-musical] play, and recorded some of the songs from Porgy and Bess in 1938.” (https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2012/03/porg-m02.html) The original operatic Porgy on Broadway was Todd Duncan. But as Passover approaches, all inaccuracies on the part of anyone in a rush to help his wife are forgiven.

The drama and pathos, damn.

Thank you for writing about this amazing man and his spectacular voice.

“You are responsible, and your forebears, for sixty million to one hundred million black people dying in the slave ships and on the plantations, and don’t ask me about [Stalin], please.” I guess you call that What-About-Ism.

A fellow US-born long-time expat to Israel said to me: “My grandparents were born in Europe 40 years after emancipation. I left the US at the age of 30. Why do I feel responsible for the enslavement of Africans?”

Great post, Jeff. Happy Pesach!